Nanoparticles could detect tiny tumours months earlier than an MRI scan, study finds

Infrared light-emitting nanoparticles can home in on, and reveal, microscopic tumours around the body that would be invisible to other scans and allow them to be treated, scientists have found.

The technology could detect these cancers, known as micro-metastases, months before they could be seen with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

This could improve survival rates by catching cancer cells that have spread around the body before they can become a harmful tumour.

Lead scientist Dr Steven Libutti, director of Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in the US, said: "The Achilles' heel of surgical management for cancer is the presence of micro-metastases.

"This is also a problem for proper staging or treatment planning.

"The nanoprobes described in this paper will go a long way to solving these problems."

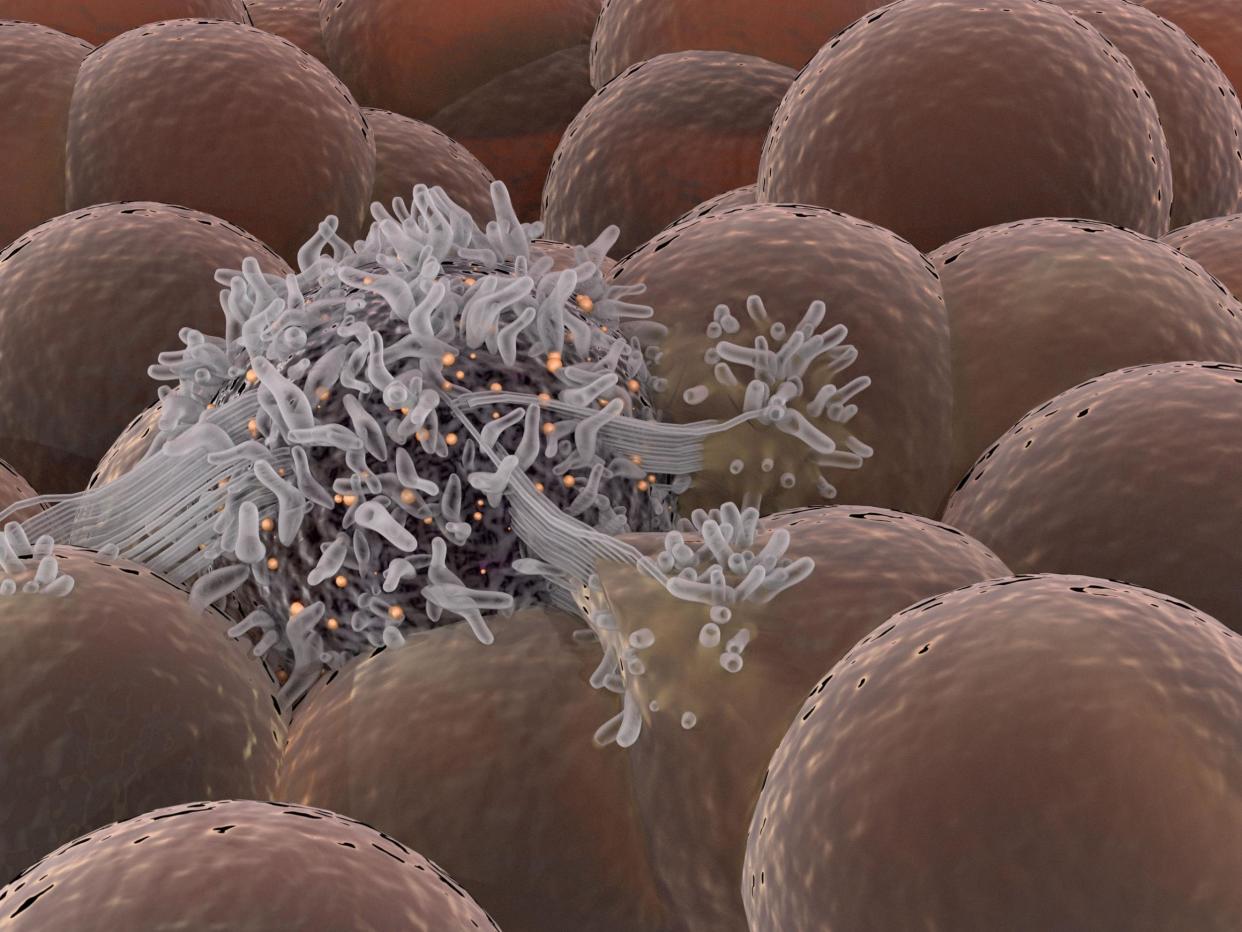

Each injected nanoparticle acts as a microscopic optical device that emits short-wave infrared light when illuminated by a tissue-penetrating laser.

Carried through the bloodstream, the tiny particles are designed to latch on to specific cancer molecules and target small hidden tumours.

When the nanoparticles "light up" they reveal places where the cancer has scattered throughout the body. These can be detected using a special camera.

In tests on mice, researchers were able to spot tiny tumours and follow their spread through multiple organs.

The nanoprobes were significantly faster than MRI at tracking tiny amounts of cancer migrating to the adrenal glands and bones.

In human patients, this would probably translate to potentially life-saving cancer detection months earlier, said the scientists whose findings are reported in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

The paper says: "We demonstrated that appropriately sized rare-earth albumin nanocomposites are able to home to micro-metastatic lesions in the long bones and spine in multiple in vivo breast cancer models."

This allowed monitoring of a diverse range of tumours, and the paper suggests a cocktail of these nanoparticles could detect a wider range of cell interactions.

Co-author Dr Vidya Ganapathy, from the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Rutgers University, said: "Cancer cells can lodge in different niches in the body, and the probe follows the spreading cells wherever they go.

"You can treat the tumours intelligently because now you know the address of the cancer."

The technology can be adapted for any of the 100-plus types of cancer and could be available to patients within five years, researchers said.

Additional reporting by PA

Yahoo News

Yahoo News