Naqqash Khalid On Crafting His Bold Debut ‘In Camera’ & Working With Nabhaan Rizwan: “I Wanted To Create What I Hoped Would Be A Generational Portrait” — Karlovy Vary

For writer-director Naqqash Khalid, questions are more important than answers and this premise is something the academic-turned-filmmaker explores heavily in his debut film In Camera, which recently premiered at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival. The bold film, which opened to positive reviews after it screened in the fest’s Proxima section last week, is the first feature to come out of the 2019 iFeatures slate, the low-budget Creative UK scheme from the UK’s BFI Film Fund and BBC Film.

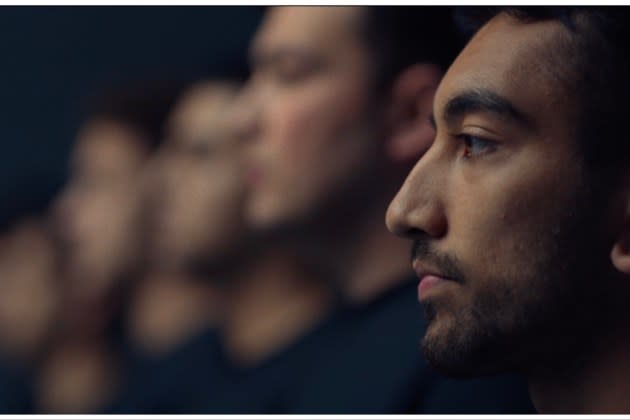

In Camera is a satirical drama that follows Aden (played by Nabhaan Rizwan), an actor who is hoping to break into the UK film industry but faces a series of challenges that make him question his desire to be accepted by a system that wasn’t built to include him. After a cycle of nightmarish auditions and multiple rejections, he finally lands a job role-playing as the dead son of a grieving mother (Josie Walker) going through therapy.

More from Deadline

'Blaga's Lessons' Review: Brutal Drama Packs A Provocative Punch - Karlovy Vary Int'l Film Festival

'The Hypnosis' Review: Norwegian Satire Skewers Start-Up Culture - Karlovy Vary Int'l Film Festival

Karlovy Vary's Eastern Promises Industry Section Announces Award Winners

The film, which was shot across six weeks in 2022 in Manchester, UK, is produced by former BFI exec Mary Burke, via her new Public Dreams banner, and Juliette Larthe of Prettybird. Sarah Mosses’ Together Films is handling world sales on the title.

Deadline sat down with Khalid to talk about his unusual approach to his first feature, collaborating with Rizwan and why he refrained from making a didactic and political film, preferring instead a more subtle approach to complicated themes that causes the audience to ask questions and reflect on life in a highly performative society.

DEADLINE: How did you conceive the idea for this film?

NAQQASH KHALID: In a weird way, it feels like everything I’ve ever done, such as my shorts Parts and Stock, have been in response to a post-Brexit world and 2016 as a year. I remember it just feeling like such a chaotic and confusing, weird and jarring year and I had these ideas I wanted to explore to find new social realism or naturalism. I wanted to say these specific things in an elevated way. It took four or five years of figuring out how I could do that. But I knew I wanted to write a film like a music track, with a side A and side B. In 2018, I went to pitch it to iFeatures and said I wanted to create a film that felt like pop music and was structurally very specific. Structure and abstract ideas are important to me and I always start with a feeling and think about how I can translate that feeling.

DEADLINE: What kind of feelings were you kind of hoping to kind of convey from your mind as a director? And what material inspired you?

KHALID: I was watching a lot of the British new wave films and I just remember being so inspired by how fluid the filmmaking felt and how these men in all of these different films felt very specific but it was almost like you put them all together and they painted a picture of a generation. There’s something really interesting about people like Richard Harris, Alan Bates and all of these actors from these angry young men films. Then I started thinking about today and how the angry man has kind of dissolved into this anxious young person.

I feel like actors are almost like sociological documents and you can see so much of our time and generation in an actor’s body. If you watch films from the 1960s, you can see so much discontent, so much working-class anger and so much confusion in those bodies. How these performers carry the frame and navigate those things have a real visceral feeling of that era and time. Today, there’s so much anxiety with young people and I wanted to create what I hoped would be a generational portrait. At the moment, it feels like we’re performing all of the time, whether it’s on Instagram or with our friends. We live in such a high performative time. With this film I was thinking of the resistance of that. This sounds quite abstract and academic, but these geometric abstractions slowly became the genesis of the film.

DEADLINE: How much of this is based upon your own experience as a young man in society today?

KHALID: I think there is a shared alienation today in society that I wanted to tap into. How do you navigate spaces and systems that are not built for you? Passivity is something that is often used as a coping mechanism as one learns to navigate spaces safely. In this film, I feel like Aden is so passive for a long time and then it’s almost like the film is him coming into agency. In answer to your question, I think when you’re an artist, you can’t escape yourself and you’re always trying to sometimes articulate things you don’t even know about yourself.

DEADLINE: Let’s talk about Nabhaan Rizwan, who does an amazing job of playing Aden. There’s a lot of subtexts with this role and there’s a lot of things he says just with his gaze and minimal dialogue. Tell me about how you cast him for the lead role and the process of working with him?

KHALID: I knew this role was going to require a lot of physicality and when I sent him the script and had a general meeting, we got along right away. I remember we spoke to a lot of actors, but they just didn’t have the same fit as he did and he just happened to be the first person I met. I just instinctively felt he was right. Then we spent nine or 10 hours just going through the script and we bonded and went over ideas, which I would rewrite around this. We were just very, very collaborative. As a director, my favorite thing about this media is the collaboration and working with actors.

We built Aden over a six-month period very forensically. But what is interesting – and we would both agree – is that we still don’t know him. His character is essentially an alien, so we don’t need to create a backstory because of this alien identity. I also wanted to creatively interpret that this is an Asian character but we’re going to withdraw his Asian backstory and treat him like an alien. There’s almost like a white gaze that comes with that.

The ambition of Nabhaan’s performance in the film is for it to feel deeply present at all times and for it to feel like live cinema, very gestural and very quiet. And that’s difficult as an actor when you’re stripped of language and the cameras are close to your face. But we had such a long preparation in our conversations, and we really trusted each other and we were able to really tap into being very present. He’s an incredible artist and very clever and a real co-author of the character.

DEADLINE: You explore the role of actors throughout this film and how they are objectified and essentially treated like pieces of meat as they begin their careers auditioning for roles. This was presumably very intentional.

KHALID: Yes definitely. Essentially, if you strip it down, it’s about a person navigating late capitalism. As an actor, you’re kind of seen as a product and you’re stripped of your agency. Acting and the film industry is used as a vehicle to talk about all of the things I want you to talk about such as identity, which is so present in this industry. Being an actor, you can’t separate your labor from your body. In this film, Aden can’t not be a young Asian man so when making this film, I had to really decolonize my own mind. I learned that the camera is such a tool of colonialism. Being a director who is Asian doesn’t make me immune to reproducing whiteness. How I look at everything, from the use of facial hair to how people look at me in the film, it felt like it was an act of decolonizing my mind. The camera was a tool that was initially invented to send photographers to take pictures of colonised subjects and bring them back so, in a way, you’re already inheriting these biases and then you have to go through a process of reclaiming.

DEADLINE: What do you hope audiences take away from this film when it comes to the themes of race?

KHALID: There’s a lot of radical politics throughout the film, whether it’s the politics of abolition, whether it’s colonialism or navigating quiet spaces. Every frame is loaded with it. But I didn’t want to write and direct a film that was didactic in anyway. Instead, I wanted to film an ambiguity that leaves the audience with questions and doesn’t provoke. These people are going on a journey, and it doesn’t have to feel smoothed out or neat. I am personally obsessed and fascinated with questions, and I just want to leave people with lots and lots of questions. The most exciting thing for me about filmmaking is that relationship with an audience.

DEADLINE: He plays the role of a son who has died in therapy session for a mother. How did you come up with this idea and use it as a tool to explore themes of loss?

KHALID: A friend of mine is an actor and I remember her telling me that she was playing someone’s girlfriend in therapy, and I was so fascinated by this idea of a real actor going into therapy and doing role play in a therapeutic setting. I didn’t do too much research as I just wanted to do something without feeling like I was bound by rules. But I did think of his role in this as like slavery, in a way, and how people were raised as slaves and there would be this emotional bond but then they were still subjugated. So, it was all of these complicated things.

As an academic, I was dealing with a lot of young people who were suicidal. I was a personal tutor for 60 students and I remember finding it very troubling that lots of young male students in particular felt very suicidal. And I was reading a lot about how the suicide rates of men are an epidemic in this country and around the world.

So, I was reading a lot about those things, but I didn’t want to tie it too closely to anything that was real. I wanted it to be imagined and I wanted the idea that it’s best as an actor who isn’t booking any jobs but who does this job in real life and it becomes the most emotionally fulfilling thing he’s done and he’s seen as an artist in a sick way.

DEADLINE: What was the big lesson you learned from getting this first feature off the ground?

KHALID: Most people will say the same thing and it’s true to me but the most difficult thing about making an independent film is time. You have all of these ambitions and ideas but then you must contend with the logic of a call sheet and a schedule for the day so you’re always up against it. But this is a super ambitious film for this kind of scale.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Best of Deadline

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

SAG-AFTRA Interim Agreements: List Of Movies And Series Granted Waivers

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News