How Nazis destroyed Berlin’s burgeoning LGBTQ+ sexology institute

In the decade before Hitler’s rise to power, Berlin was experiencing a cultural, creative and economic boom. Known as the ‘Golden Twenties’, attitudes towards sexual minorities during this time in the Weimar Republic were becoming increasingly liberal. Bars where LGBTQ+ people could meet and live openly were commonplace and in 1919, a leading sexology institute focused on researching sexuality and gender issues was founded in the city.

Established by gay Jewish sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, or Institute for the Science of Sexuality, is widely recognised as the first sexology research centre in the world. At its peak, more than 40 people worked at the institute, which housed a major archive, research library, museum, medical examination rooms and a lecture hall.

Pioneering Research

Psychiatrists, gynaecologists, sex educators, dermatologists and librarians all worked at the sexology institute, researching a diverse range of issues around gender and sexuality. Radical studies were undertaken to better understand complex and, at the time, extremely controversial questions related to sexual and gender orientation, intersexuality and reproductive health.

Hirschfeld was at the forefront of research into trans issues, with the sexologist coining the term ‘transsexual’ in 1923. Trans people were employed by the institute and were also able to access essential services that were not available anywhere else, including facial feminisation surgery and facial masculinisation surgery.

There’s no question these surgeries were experimental and came with clear risks due to the medical technology available at the time. Alongside Hirschfeld, surgeon Ludwig Levy-Lenz worked closely with trans patients to start hair removal treatments and advocated for their rights to Berlin police officials.

Trans people and cross-dressers faced arrest by police in the city when wearing clothing deemed only suited for people assigned a different gender at birth. Transvestite passes were issued by the sexology institute that trans people could show to police to avoid arrest.

Hirschfeld became well-known for this outspoken advocacy for LGBTQ+ rights and founded the first LGBTQ+ rights organisation called the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in 1897, which was based at the centre before it was destroyed by Nazi supporters in 1933.

During further ire from extreme social conservatives and the Nazi Party, the institute placed a major focus on sexual and reproductive health. From offering access to contraception to providing marital counselling and gynaecological services; Hirschfeld created an Institute where even Berliners with little money could visit and obtain much-needed services.

High-profile academics, medical specialists and intellectuals, such as birth control advocate Margaret Sanger and British archaeologist Francis Turville-Petre, visited the sexology institute as its research became more prominent. But Hirschfeld strongly believed it was vital for the Institute’s work to be accessible to the wider public and not only to experts.

To better interact with the public, the institute purchased a neighbouring building in 1922, where lectures were held to inform locals about the latest breakthroughs in sexuality and contraception research.

Many Germans found Hirschfeld’s work to be immoral and ‘un-German’, leading to a Nazi press campaign against him targeting his sexuality and Jewish ancestry. When visiting Munich in 1921, Hirschfeld was violently attacked by Nazi supporters and left wounded. A front-page article published in the Nazi newspaper Der Stuermer in 1929 featured a caricature of Hirschfeld and attacked him for his research.

Recognising the growing power of the Nazi Party in Germany, and after facing threats, Hirschfeld left the country and moved to Switzerland sometime before Hitler became chancellor in 1933.

Book burnings

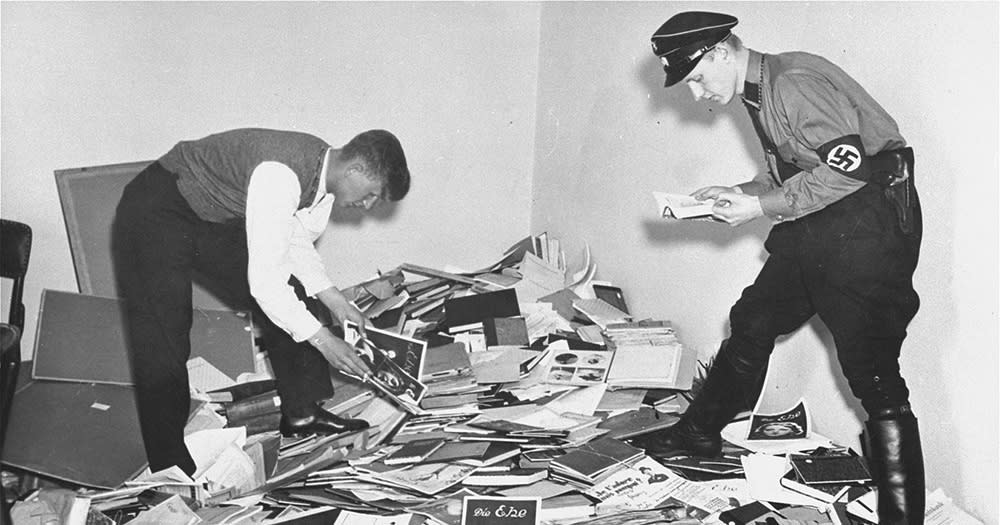

The institute was targeted as part of widespread book burnings of so-called ‘un-German’ and ‘degenerate’ literature during the Third Reich. On May 6, 1933, just months after Hitler became chancellor of Germany, members of Nazi student groups ransacked the Institute in an organised attack.

Thousands upon thousands of books, documents and other items were stolen from the building, with the interior defaced and virtually destroyed. Following the looting by Nazi students, members of the Sturmabteilung, the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party, joined the attack and pulled out what was left inside the archives and library to burn.

Before the book burning, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels gave a speech to the assembled students, Hitler Youth members and other Nazi groups saying, “The era of exaggerated Jewish intellectualism is now at an end… and the future German man will not just be a man of books… this late hour entrust to the flames the intellectual garbage of the past.”

While estimates differ, it’s believed tens of thousands of books were burned on May 10 in the Bebelplatz public square. Books written by authors such as Maria Remarque, Heinrich Heine, Karl Marx and Albert Einstein were also destroyed.

Today, a memorial called The Empty Library stands beneath Bebelplatz, containing shelves of empty bookcases representing the void created by the book burnings. An inscription reading, “Das war ein Vorspiel nur, dort wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man am Ende auch Menschen” (That was only a prelude; where they burn books, they will in the end also burn people) from Heinrich Heine is engraved on a plaque in the square as a reminder of the horrors experienced in recent history.

In the aftermath of the Nazi raid on the sexology institute, alongside the purge of gay men from the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party on the so-called Night of the Long Knives, far more draconian laws were yet to come. Based in part on address lists stolen from the Institute, the Nazi Party rounded-up men who were believed to be queer and placed them in either labour or death camps.

Lost Histories

Despite the best efforts of the Nazi regime, the work Hirschfeld started more than 100 years ago has not been forgotten. Exhibitions, conferences and books have since been created about the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft to ensure that as much information as possible is available about the groundbreaking research conducted by Hirschfeld and his team.

Everything from unpublished photographs, documents and research have been widely shared in recognition of the pioneering role played by researchers at the institute. These events may have taken place more than 90 years ago, but for Brandy Schillace, medical historian and Editor in Chief of BMJ Medical Humanities, the parallels between the 1920s and the 2020s are impossible to ignore.

“It simultaneously sounds a warning,” explains Schillace. “Anti-LGBTQ joined anti-semitism as two planks of the Nazi platform; they used hatred of the other to fuel their rise. It can happen again. Hate crimes start with those on the fringes, but they do not end there.”

It’s difficult to quantify exactly what has been lost from the destruction of the sexologist institute. However, it is clear that a great deal of early research and personal testimonies of LGBTQ+ people had been eliminated during the attacks and book burnings.

“Posters, portraits, artwork, and archives of 35,000 photographs were slashed and destroyed; the books, however, these were carted away,” adds Schillace.

“Four days later, more than 25,000 books would be hauled into Opernplatz, the central square of Berlin, and set alight. The case histories of patients, the details of how they were treated, the transformations documented, and lots of ephemera went up in smoke,” concludes Schillace.

The post How Nazis destroyed Berlin’s burgeoning LGBTQ+ sexology institute appeared first on GCN.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News