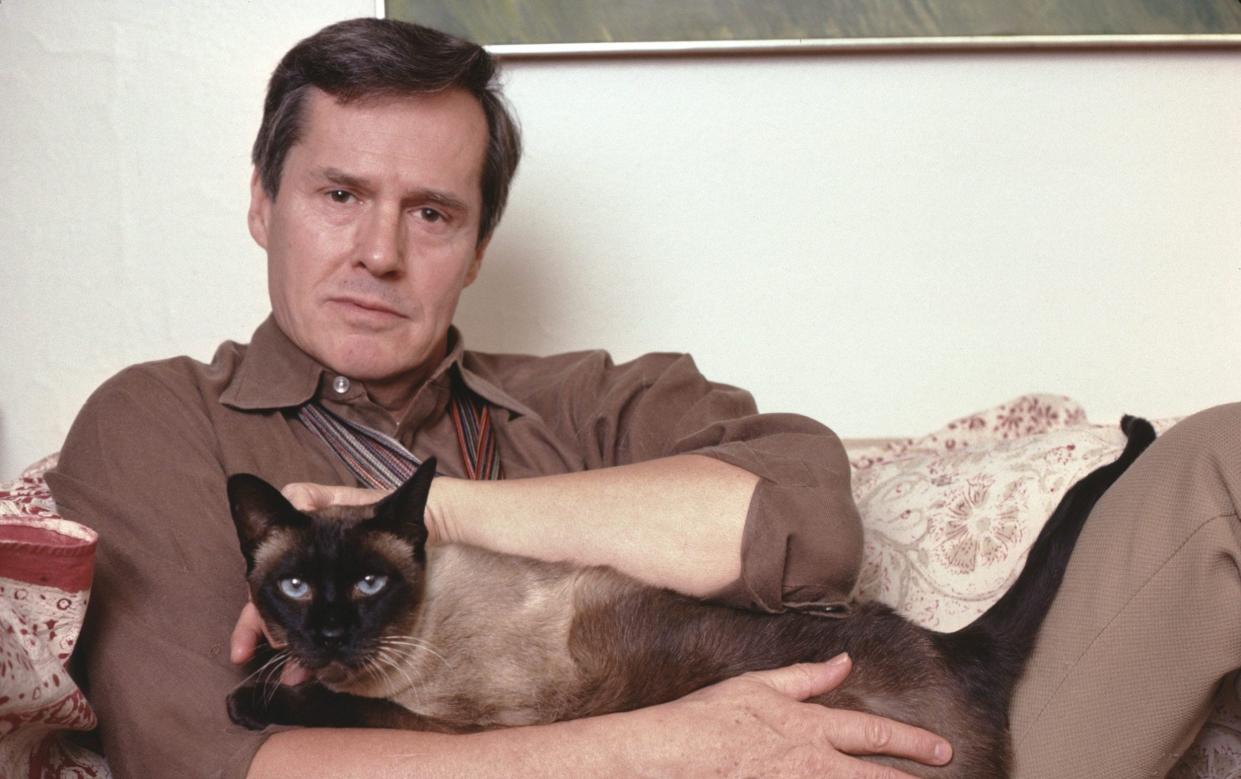

Ned Rorem, prize-winning American composer, socialite and confessional diarist – obituary

Ned Rorem, the American composer, who has died aged 99, was variously described as “the world’s best composer of art songs”, and as “an imaginative social climber”.

Gifted, good-looking and sharp-witted, Rorem established his reputation in the early 1950s, when he lived in Paris as a protégé of the Vicomtesse Marie-Laure de Noailles, the artist and patronne of modernism. In his confessional diaries, for which he remains best known, Rorem revealed a world of licentiousness and indiscretion, ambition and intellectual and artistic curiosity – and emotional complexity.

An inveterate name-dropper – such figures as Noël Coward, Truman Capote, Pablo Casals, Virgil Thomson, Picasso, Alice B Toklas and Zsa Zsa Gabor pepper his pages – Rorem emerged as narcissistic, hedonistic and unashamedly self-seeking, but with a talent for self-mockery and incisive, acerbic prose: “To become famous I would sign any paper,” he wrote.

Ned Rorem was born on October 23 1923 in Richmond, Indiana, of Midwestern parents of Norwegian ancestry. He was brought up a Quaker, which he remained throughout his life, despite his later wayward bohemianism and fondness for alcohol.

He was educated at public schools in Chicago, and from 1940 to 1942 attended Northwestern University music school, studying composition in Chicago with Max Weld. “When I was young,” he told an interviewer, “it was a toss-up whether I would be a composer or a writer, so I became a little of both.”

In 1942 he received a scholarship to the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, graduating in 1947. From 1944 he lived on East 12th Street in New York. He continued to study music, including with Bernard Wagenaar at the Juilliard School, where he took a master’s degree in 1949, and intermittently at the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood, Massachusetts, as a pupil of Aaron Copland.

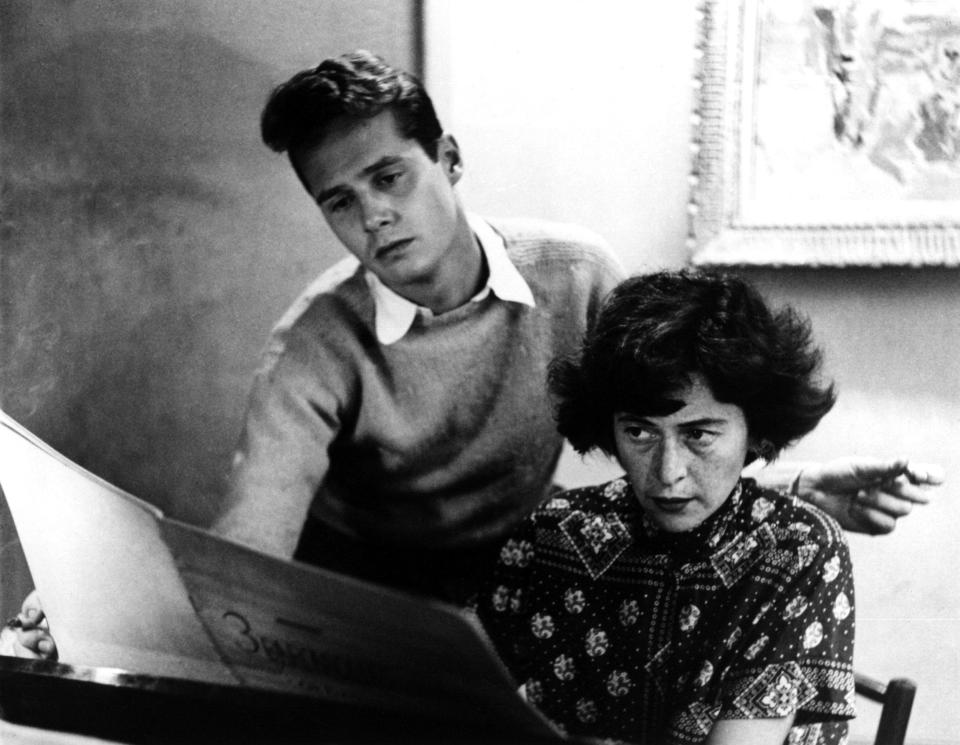

He also studied under Virgil Thomson, receiving lessons in return for his work as a copyist (Rorem’s early career was sustained by such work for various companies). In 1948 he received two awards for his compositions, one of which – Overture in C – was performed by the New York Philharmonic.

Rorem arrived in Paris in the Spring of 1949 intending to spend just one summer in France, but remained in the city, on and off, for six years. Early on there were interludes in Morocco (where he befriended Paul and Jane Bowles) and Italy (where he met Iris Tree and decided to write pop songs with her). He returned to Paris early in 1951, and made contact with names such as the artist Balthus, the poet and dancer Boris Kochno, the writer Julien Green, and the Comtesse Marie-Blanche de Polignac – also introducing himself by “flirtatious letter” (and enclosed photograph) to André Gide and Jean Cocteau.

The Vicomtesse Marie-Laure de Noailles, to whom he was introduced before these travels, took some time before she would accept him as anything more than a handsome waster, but in 1951 she gave in to his “abject persistence”, and invited Rorem to her Hyères villa for a month.

At a party given by her to celebrate a broadcast of his Six Irish Poems, Rorem, drunk on success and alcohol, ran up behind his hostess and slapped her on the back, so heartily that he was restrained by the maître d’hôtel: “But the noble hostess motioned for them to release me, then rose with a bemused stare of utter satisfaction: somebody new cared.”

Paris was the making of him, his friends including fellow American expatriates and his French neighbours in the 16th arrondissement. He was successful and prolific: he won the Lili Boulanger Prize in 1950, and a Fulbright Fellowship in 1950-51 to study with Arthur Honegger.

Within a few years Rorem had produced numerous symphonies, quartets, sonatas, concertos, five song cycles, three ballets and an opera. His ballet of Dorian Gray was performed in Barcelona in 1952, but, by his own admission, “flopped ignominiously”.

He first achieved recognition with his songs, described by his fellow composer William Flanagan as “terribly pretty” with an “expressive intent that is ... immediate, clear and above all, right”. They have been extensively performed and recorded, though it was not 1998 that his Evidence of Things Not Seen, a hugely ambitious song cycle for four singers and piano, incorporating 36 poems by 24 authors, was first performed. Many admirers regard it as his masterwork.

In his other works, Rorem came to be judged as “the first successful modern romanticist”, placing importance equally on emotion and lyricism. He had little time for the avant garde: “If I am a significant American composer it is because I’ve never tried to be New,” he explained.

After he returned to the United States in 1955, the Louisiana Orchestra presented the premiere of Rorem’s orchestral Designs, and subsequent symphonies were introduced at La Jolla, California, in August 1956, and in April 1959 by the New York Philharmonic, conducted by Leonard Bernstein.

His choral work The Poet’s Requiem was heard in New York in 1957; an opera, The Robbers in New York, in 1958; and a tone poem, Eagles, in Philadelphia in 1959.

In 1957 Rorem received a Guggenheim scholarship and became composer-in-residence at the State University of New York from 1959 to 1961, and at the University of Utah in 1965-66.

In 1965 his first full-length opera, Miss Julie, based on Strindberg’s play, had its New York premiere, and was judged, by The New York Times critic, to be the work of an “experienced, sensitive composer” who “knowingly blends realism with dreaming” – although the critic also complained of the work’s “blandness … All was very polite and innocuous”.

In 1976 he won the Pulitzer prize for his Air Music, an orchestral suite commissioned by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra.

Rorem’s published diaries comprise volumes dealing with his Paris, New York and Nantucket periods, as well as an additional volume of The Later Diaries, his subjects encompassing not only music and art, but death and illness, depression and insomnia, and the problems of living as a homosexual (he claimed to have slept with around 3,000 men) at a time when same-sex sexual activity was illegal in much of the western world.

He could be pithily epigrammatic: “Profundity is for the young”; “Everyone weeps after sex not from fulfilment but from pointlessness”; “The one thing worse than a dumb bigot is a smart one” and self-revelatory: “If I could cause one heart to break, I should have lived in vain”

Above all, however, he was indulgent, both of himself, and of his peers and their failings. He remained a vain man, as he admitted in his Paris Diary following a series of mishaps: “Famous last words of Ned Rorem, crushed by a truck, gnawed by the pox, stung by wasps, in dire pain: ‘How do I look?’ It’s harder to maintain a reputation for being pretty than for being a great artist.”

In 1967, he met James Holmes, an organist and composer who became his partner, sharing an apartment in the Upper West Side of Manhattan and a house in Nantucket.

After Holmes’s death from Aids in 1999, Rorem played an active role in Aids awareness.

Ned Rorem, born October 23 1923, died November 18 2022

Yahoo News

Yahoo News