Netflix Is the King of Streaming. Is It a Benevolent Dictator?

In Netflix’s global smash hit Squid Game, the penultimate challenge sees the last few surviving competitors make their way across a glass bridge. One wrong move, and the player falls to their demise.

But as the players progressed, they hit upon a revelation: Yes, there will only be one winner of the final game, but if they work together, they can cross the chasm and survive for one more day.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Behind Netflix Film Chief's Exit - And What It Means for Streaming Movies

'It's What's Inside' Review: A High-Concept Mind-Bender With Style to Burn, if Not Substance

Netflix Settles Defamation Suit Brought By Cuban Exiles Over Spy Thriller 'Wasp Network'

Netflix, led by co-CEOs Ted Sarandos and Greg Peters, has won the streaming wars (Morgan Stanley proclaimed it “The Undisputed” in a Jan. 23 research note, and the next day Bernstein declared the company “clearly the winner in streaming”), and the company and Wall Street see plenty more room to grow.

But even as Netflix appears poised to reign as the streaming champion, it also finds itself more open than ever to partnering with its competitors-turned-suppliers, perhaps even helping them get through the messy slog from linear TV to streaming…all with a healthy dose of self-interest, of course.

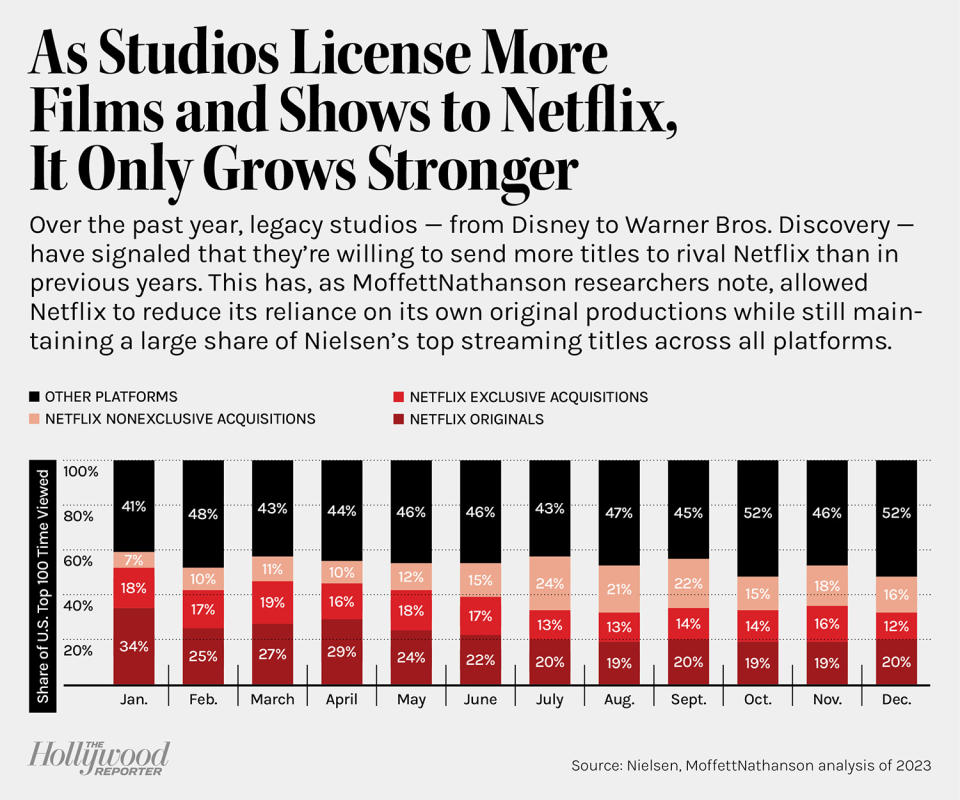

It’s a counterintuitive thing, and yet: Netflix appears more eager than ever to acquire films and TV shows from other studios, and is paying substantially more than it did in the early days of streaming, when those same studios sold their content — the “lifeblood” of their business — “for pennies on the dollar,” MoffettNathanson’s Michael Nathanson noted in a Jan. 24 report.

And perhaps more significantly: As Netflix leans into advertising as its big growth opportunity, it is floating the idea of more aggressive and opportunistic bundles with those same companies. (Could a Netflix-Max-Peacock discounted offering be on the horizon?)

“We’re still very much in the early days of the ‘turn-a-profit phase’ for streamers and I’d expect to see less content and more bundling, ads and long-term subscription offers as the business of streaming matures,” says Scott Purdy, national media industry leader for KPMG. “[Tuesday’s] results show going back to the basics — ads and bundling — will be the blueprint other streaming companies follow to turn a profit.”

For other companies in streaming, the rush to turn a profit has turned into a battle against churn. It isn’t just about acquiring new subscribers, it’s also about keeping them. And it turns out bundles are an effective way to reduce churn.

“Lower-priced tiers and bundles that spread out costs could make it easier for more people to maintain subscriptions — and for streamers to sustain revenues,” the consultancy Deloitte wrote in its 2024 TMT Predictions report.

Indeed, on its quarterly earnings call, Netflix co-CEO Peters, when asked about striking deals with partners on bundles, was enthusiastic about their potential to boost the company’s ad tier.

“It’s very effective, very useful for us because that lower consumer-facing price means that we’ve got room now to bundle the ads plan into a set of lower-priced partner offerings where it was hard to make the economics work for everyone previously,” Peters said. “So we really think of this as a win-win-win and we’re going to continue to leverage these bundles going forward.”

Verizon currently offers a bundle of ad tiers of Netflix and Max for $10 per month, but Peters’ comments certainly suggest that more bundles are imminent.

And then there’s the licensed content. By now everyone in Hollywood knows that Netflix is an eager buyer of films and series. In fact, Netflix seems to have become the buyer of choice for many companies. What other platform has Sex and the City, Grey’s Anatomy, Star Trek: Prodigy, The Super Mario Bros. Movie in one place?

Or to hear Sarandos explain it: “I am thrilled that the studios are more open to licensing again, and I’m thrilled to tell them that we are open for business.”

“Against all odds, Netflix has succeeded in disrupting an industry where the incumbents once held the single most important resource: control of proprietary IP,” Nathanson added. “Even though this strategy is making Netflix stronger and more efficient, Netflix’s competitors appear willing to keep feeding the beast.”

But there may be a method to the madness, and a clear rationale, for both Netflix and the other entertainment giants. Yes, Disney, Paramount, WBD et al are getting paid, but Sarandos argues that streaming their shows on Netflix helps their platforms, too.

“Because of our recommendation and our reach, we can resurrect a show like Suits and turn it into a big pop culture moment,” Sarandos said. “I believe because of our distribution heft and our recommendation system that we can uniquely add more value to Studios’ IP than they can. Not all the time, but sometimes, and we’re the best buyer for it.”

It’s also part of the argument for the $5 billion WWE deal, with the wrestling company still trying to expand beyond the United States, Canada, U.K. and a handful of international markets.

“WWE can leverage Netflix’s global reach and massive subscriber base to grow awareness of the sport in new international markets,” Bank of America’s Jessica Reif Ehrlich wrote Jan. 23.

And not only does Netflix receive a constantly refreshed fountain of content with these deals, but it can also land some legitimate bargains. With a deep menu of content from other companies to choose from, “it might be that we can deliver more on our programming spend with some licensed titles,” Sarandos acknowledged Jan. 23.

Despite the olive branch, a top advertising source expressed caution, comparing Netflix’s strategic moves to letting a fox into the henhouse.

Netflix’s ad business is small, and it does not expect it to be a meaningful driver of revenue this year. That is expected to change in 2025. The concern for the likes of Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery and NBCUniversal is that as Netflix scales up its ad business, it will come for their ad dollars, siphoning budgets that would otherwise be going to broadcast or cable TV, or streaming services like Peacock or Paramount+. It’s a threat looming from Amazon Prime Video, which will turn on ads for its members Jan. 29.

“Given its size, Netflix can amortize the content it licenses from competitors across a larger subscriber base and as the ad plan rolls out can sell more ads on a single piece of licensed content,” Macquarie analyst Tim Nollen wrote in a Jan. 24 note.

In other words, Netflix may be able to monetize acquired content better than the third-party studios can, a difficult situation for those companies to be in.

“Traditional media companies are back to the same place they found themselves 10 to 15 years ago: between a rock and hard place,” Nollen added, referencing the conundrum facing legacy studios: cash now, or hoard content for their own platforms? “The bigger Netflix gets, the more other studios will want to license its content, which then puts them in the familiar quandary of how to grow their own DTC services successfully in response.”

This moment in some ways is a textbook example of “what’s old is new.” The strategic shifts by Netflix are a significant departure from the company’s original streaming premise. But it’s likely to be a very profitable pivot, one that bears a striking resemblance to, well, cable TV.

The adjustments from the company “all portend for a much more profitable Netflix in the coming years,” Nathanson writes. “A few years back, at the start of the streaming wars, we argued that Netflix’s forced shift into greater and greater original content investment would be far tougher than their initial strategy of using other people’s content. Now, due to industrywide challenges, Netflix has been able to flip that model back.”

This story appeared in the Jan. 26 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Yahoo News

Yahoo News