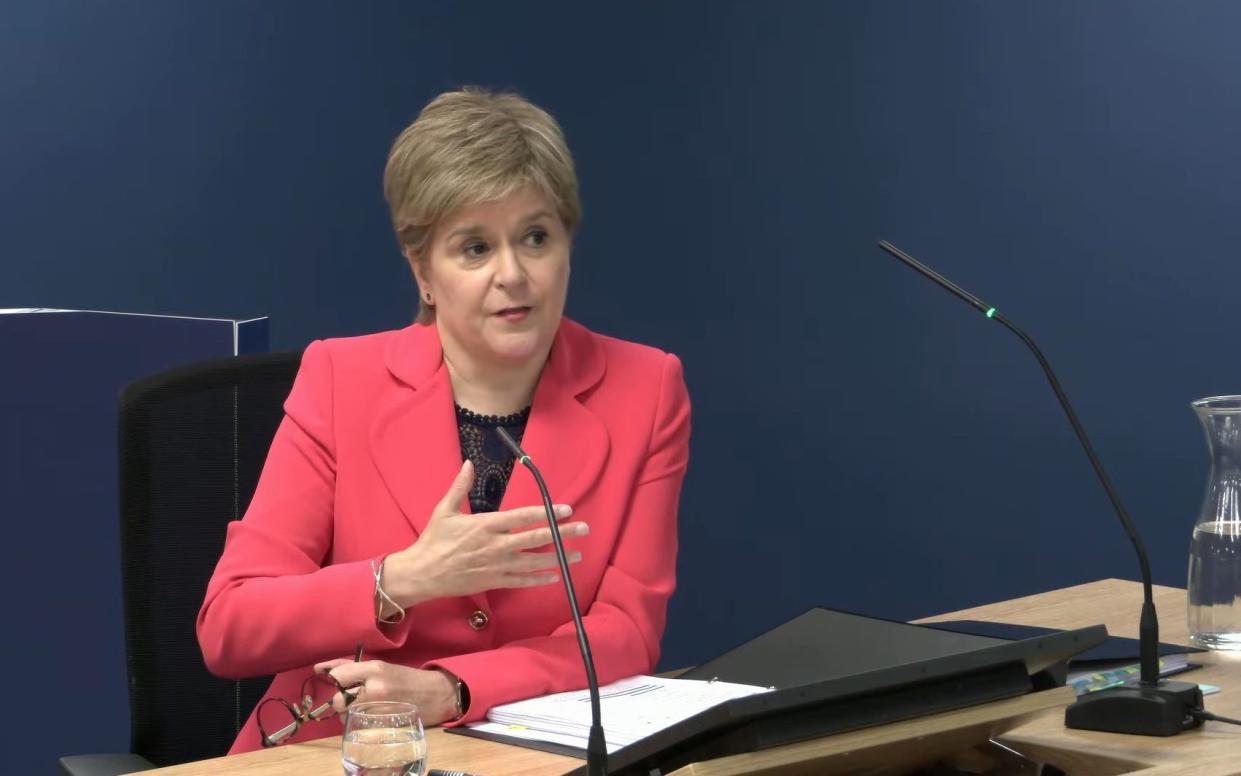

Nicola Sturgeon has difficult questions to answer

The cavalcade of the UK Covid Inquiry is camping in Scotland, leaving Lady Hallett and her team with a clear run at lawyers, politicians and witnesses from selected interest groups north of the border. Over three weeks, the inquiry will hear about the interactions between Scottish and English advisers and decision-makers as the pandemic unfolded. The Scottish government – and Nicola Sturgeon – have some difficult questions to answer.

The devolution of health services in Scotland has a long history. Many do not realise that there has never been a single UK NHS. England, Scotland and Northern Ireland were different from the start in 1948 and Wales has diverged since devolution. Before 1999, the Scottish Office had the flexibility quietly to respond to the very different needs of the different parts of Scotland. As the pandemic unfolded, however, public health became a battleground for the political tensions exposed by the independence referendum in 2014.

A key issue for the inquiry will be whether the Scottish government should have followed UK decision-making or used devolution to develop its policies based on advice and opinion from its own choice of scientists. An honest analysis of this will have to ask whether the Scottish government ended up inflicting considerably more pain on the population for very little gain.

The danger, of course, is that the inquiry will simply assume that lockdowns should have been quicker and tougher. This became the Scottish approach, with measures like masking, social distancing and the closure of schools and businesses introduced more widely, and continued for longer, than elsewhere in the UK. Matt Hancock’s leaked WhatsApp messages even suggest that the Scots bounced the UK Government into introducing face masks in schools, despite there being “no strong reasons” for it, simply in order to avoid a public disagreement. How often did the Scottish government allow politics, not public health, to dictate such sensitive areas of policy?

And did it seriously contemplate pursuing a dangerous zero Covid policy? For a brief period in the summer of 2020, Sturgeon was able to claim that, in the absence of recorded deaths, Scotland was close to eradicating the virus. This was heralded as a triumph for the Scottish government, threatened only by the less restrictive approach of Westminster. There was even talk of protecting this position by introducing some form of border control with England.

But it has long been established that eradication is only possible for viruses that meet quite specific conditions. Covid never met them and the proposition never had much support from those with expert knowledge of infectious diseases. Given the properties of Covid, even elimination from a particular area for a period of time is difficult and not sustainable, as the Chinese eventually realised.

And as they, the New Zealanders and others discovered to their cost, such policies only defer the inevitable when the pandemic is caused by an evolving respiratory virus. Even with a vaccinated population, there is a wave of sickness and deaths when restrictions are lifted. The inquiry might identify who Sturgeon was listening to and why she found them persuasive.

It certainly has to look through the politics that has clouded understanding of Scotland’s lockdown performance. At the height of the pandemic, Sturgeon rarely missed an opportunity to tell the Scottish people that her government was their real protectors with a concern for their welfare that was absent in Westminster. If only they were independent and had full control of their resources and borders, this virus could be locked out. Her press conferences were significantly less formal and technocratic than those held in Westminster.

They commonly included statements that the Scottish government could, and would, do more to protect their people, but they needed resources from the UK Government that were not always forthcoming. Funding schemes were invariably branded as coming from the Scottish government even if the money was actually being provided from Westminster.

In the end, however, from January 2020 to June 2022, overall, age-adjusted, excess deaths in Scotland were only about 0.2 per cent lower than in England, according to the Office for National Statistics. These are not specifically Covid-related deaths but are accepted as the best measure of the pandemic’s impact, given uncertainties about diagnosis and recording causes of death. Was the tougher path taken by the Scottish government really worth the cost?

Professor Robert Dingwall is a medical sociologist

Yahoo News

Yahoo News