NSW investigators face labyrinth of family trusts to claw back Eddie Obeid’s proceeds of crime

New South Wales Crime Commission investigators face a labyrinth of family trusts, loans to family members and possible offshore bank accounts in seeking to retrieve the $30m that former NSW Labor powerbroker Eddie Obeid received as a result of a corrupt deal involving a coal exploration licence at Bylong.

After public outrage that the NSW government had ruled out trying to pursue the $30m, the state crime commissioner, Michael Barnes, on Friday committed the agency to revisiting its previous investigation into whether it could confiscate any of the Obeid family’s assets as the proceeds of crime.

“Unacceptable and outrageous,” was how the NSW premier, Dominic Perrottet, described the Crime Commission’s decision to leave the pursuit of the Obeids’ ill-gotten gains to the Australian Tax office.

“It doesn’t pass the sniff test,” the opposition leader, Chris Minns, said.

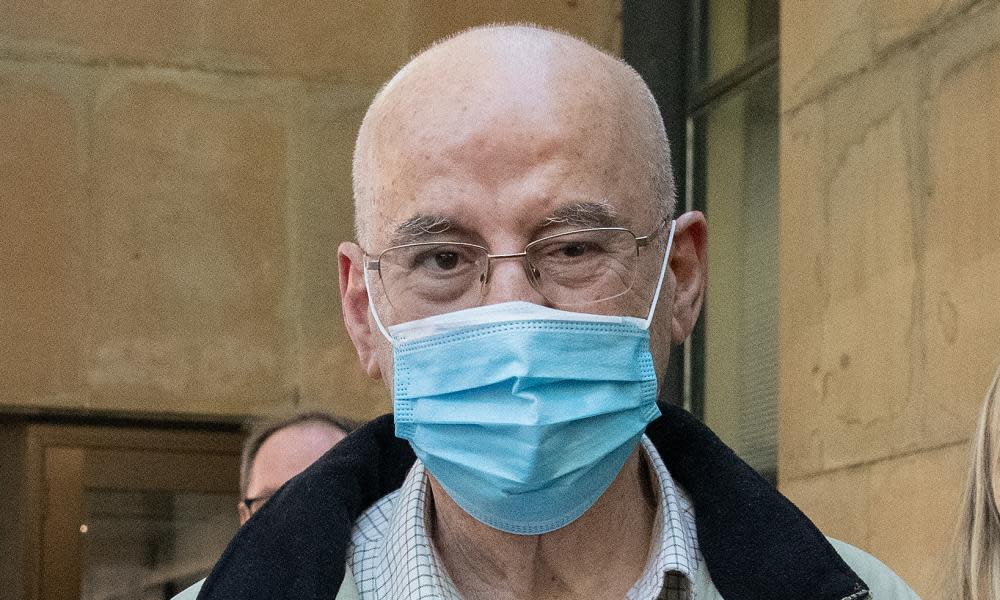

Eddie Obeid, 78, his son Moses Obeid, 52, and the former NSW minister for minerals, Ian Macdonald, were sentenced to lengthy jail terms last Thursday, after justice Elizabeth Fullerton found the three had conspired to have Macdonald wilfully commit misconduct in public office.

All three have indicated they will appeal.

But the location of the $30m – half of the $60m the mining company, Cascade coal agreed to pay under the deal – remains unfinished business.

So what do we know about where the money went?

As part of the original Independent Commission Against Corruption (Icac) inquiry in 2013, forensic investigators attempted to answer this question.

Soon after the deal with Cascade Coal was inked in late 2010, the Obeid family went on a spending spree, buying property, cars and pursuing a subdivision of prime coastal land they already owned on the NSW mid-north coast.

Grant Lockley, a senior forensic accountant at Icac gave evidence that millions of dollars had flowed to Eddie Obeid, his wife, and others from the deal, via family trusts.

He told the inquiry Eddie Obeid received $1.5m from the suspect coal transaction.

From October 2010 to June 2011, $29,459,860 was paid via an Obeid front company to the Obeid Family Trust No 2.

Two months later, Eddie Obeid used funds derived from the coal venture to buy a $286,817 Mercedes S500, Lockley alleged.

There is no suggestion that members of the Obeid family, other than Eddie and Moses, had any reason to suspect the money was the product of a corrupt deal.

He also used some of the funds to make repayments on his $1.12m holiday unit in Port Macquarie.

The family have long had an interest in prime coastal land near Port Macquarie, known as Rainbow Beach.

After the coalmine deal, the family finally secured planning approval for their massive subdivision at Bonny Hills, known as Rainbow Beach.

While Obeid senior was in jail between 2016 and 2018 after being convicted of misconduct in public office over another matter, the family companies which hold the land, have progressed the 702 lot subdivision and earned millions selling lots.

Part of the problem for Icac and later the ATO and the NSW Crime Commission has been finding sufficient paperwork to follow the flows of money through the Obeid trusts.

To recover the proceeds of crime, the Crime Commission must be able to link the funds to the criminal enterprise and that is far from simple when the same trusts are used to blend tainted money with legitimate funds.

For instance the Obeids’ family property, Cherrydale Park, which was central to the coalmine plan was bought before the conspiracy was hatched for $3.65m. The family still own it, but it may fall outside the definition of being proceeds of crime.

Then there is the sheer complexity of the Obeid empire. The Icac inquiry was told the Obeids had used more than 20 trusts to structure their financial affairs. Often members of the family were not aware they were trustees of particular trusts or indeed beneficiaries.

Instead of making distributions to the beneficiaries of the trust, payments to family members were often made as loans, with little or no documentation.

Giving evidence before Icac, the Obeids’ longtime family accountant, Sid Sassine conceded to counsel assisting, Geoffrey Watson SC that he regularly found “anomalies” in the Obeids’ financial accounts.

Related: For years Eddie Obeid fended off all allegations. Now the truth can’t be denied | Anne Davies

Adding to the difficulties of tracing the money, is the fact that some entities involved in transactions relating to Bylong were not actually in the Obeid name.

Sassine denied he was a frontman for the family, but admitted that his role as their accountant involved hiding the Obeid name from the public because the Obeid name was sometimes perceived as a hindrance to new business ventures.

“My role there is to conceal, yes, to hide the name Obeid from the general public, to avoid the hindrance that they’ve consistently had,” he said.

The difficulties in penetrating the Obeid family finances have been encountered by others as well as Icac.

In 2012, the City of Sydney council successfully sued middle son, Moses Obeid, and was awarded $12m in damages after the court found Moses’s company, Streetscape Projects had breached a licence agreement with the council involving the intellectual property in multi-function street poles known as “smartpoles”.

But in 2014 the council settled, rather than fight on incurring more costs as it sought to recoup the damages. Streetscape Projects had been placed into liquidation and the council found itself trying to chase funds through the maze of trusts.

After the Icac hearings, the ATO has also been attempting to untangle the Obeid empire and pursue tax owed.

Icac was told that the family paid $4.6m tax on $25m of “pure profit” relating to the Bylong Valley but the ATO has continued to delve into Obeid’s trust structure.

In 2014, a number of members of the Obeid family, including family matriarch Judith, were hit with a $9m tax bill that followed an audit of the Obeid family trusts for the years 2007 to 2012.

The protracted battle has been raging in the courts ever since, but was deferred last week while any appeals relating to the Bylong mining conspiracy are heard.

Eddie and Moses Obeid are also yet to pay an estimated $5m in costs they owe to parties whom they unsuccessfully sued in relation to the Icac inquiry. The Obeids lost their case against the commissioner, Justice David Ipp, Watson and investigators, Grant Lockley and Paul Grainger in 2016. They were unsuccessful on appeal and were refused the right to appeal to the high court in 2018.

The NSW Crime Commission’s role is to pursue the proceeds of crime under Criminal Assets Recovery Act 1990.

The philosophy behind the Crime Commission and similar bodies is that depriving criminals of their capital will help degrade their criminal enterprise. Information from the investigations is also passed on to other agencies.

Most of its referrals come from the NSW police, but it also gets asked by other agencies, such as the AFP and Icac to look into where the money from criminal enterprises has gone.

On its website, the commission estimates that approximately one in six referrals results in confiscation proceedings, with many cases falling by the wayside because of difficulties in pursuing the funds or the amounts are deemed not worthwhile to pursue.

The proceedings, which are civil not criminal, sometimes reach court, but most are settled with the criminal required to sign a statutory undertaking and hand over the assets. This has drawn criticism in the past because it involves a government agency doing deals with criminals in private.

Stung by the criticism on the Obeid case, the Crime Commission released a rare statement about its activities last week.

“Between 2013 and 2015, the NSW Crime Commission undertook extensive forensic financial investigations attempting to identify property that could be seized and forfeited as proceeds of crime,” Barnes said.

“We liaised with ICAC officers and were kept apprised of that agency’s investigations into Obeid and others. We briefed a QC with extensive experience in the area”.

“Senior Counsel’s advice at the time was that there were no reasonable prospects of recovering the proceeds of any Criminal Asset Recovery Act orders that might be made. For that reason, the cost of pursuing such orders could not be justified, the statement said.

Barnes said that the commission would again review the material it had. But it is entirely possible that the Crime Commission will encounter the same difficulties as last time.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News