NY governor's subway mask ban proposal sparks debate over right to anonymous protest

NEW YORK (AP) — A new proposal by Gov. Kathy Hochul to ban masks on the New York subway is drawing backlash from civil liberties groups and disability advocates, reviving a long-standing debate about the right to anonymous protest that has only grown more complex since the pandemic.

Hochul, a Democrat, backed the idea this week following a spate of confrontations involving masked pro-Palestinian activists that the governor and others have characterized as antisemitic. She said the legislation — which has not yet been crafted — would include “common-sense exemptions” for those who cover their faces for medical or religious reasons.

If the ban does go into effect, New York would join a growing number of states that have embraced laws against public masking to clamp down on activists who conceal their faces at protests.

But the new restrictions raise constitutional questions, according to Jay Stanley, a policy director at the American Civil Liberties Union, since they appear aimed at stopping a specific group from an activity that is widely practiced by members of the public.

“Because mask wearing is such a broad activity, done by so many people for so many reasons, it creates a real danger of selective prosecution against disfavored groups,” he said, adding that “COVID completely scrambled the contours of the debate over arcane mask laws.”

New York previously banned public mask-wearing by groups of three people or more under a law dating back to the 19th century, when upstate tenant farmers dressed as Native Americans and rose up violently against landlords. The law was lifted when COVID-19 struck.

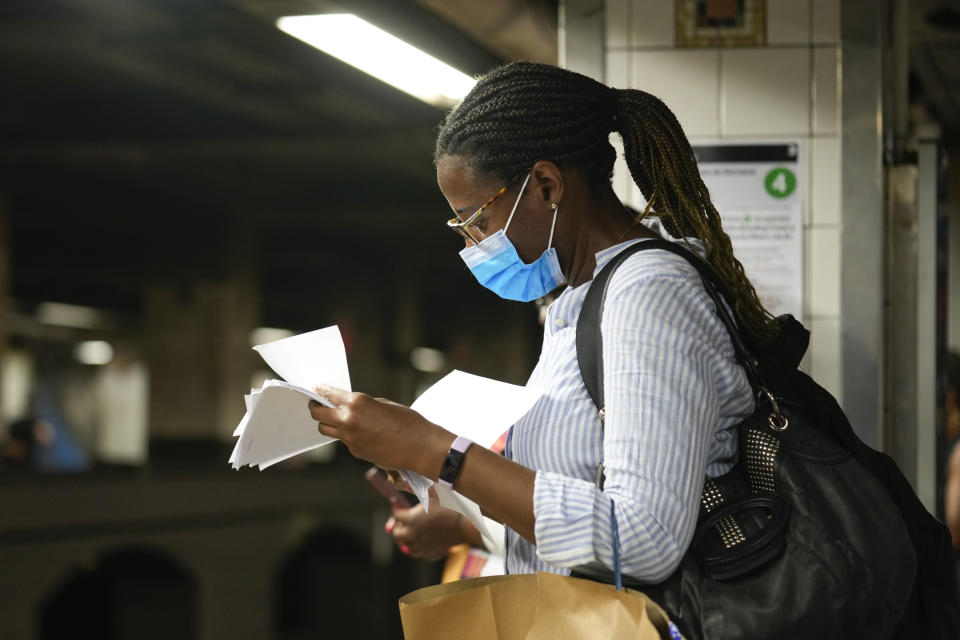

Until two years ago, riders were required to wear masks on public transit.

The effort to reinstate the ban has also rankled the many people who still mask on the subway to protect themselves from the virus, spurring a campaign among disability advocates to pressure Hochul’s office against the idea.

Jason Roth, a Brooklyn resident who suffers from an autoimmune disease, said the measure would only “further stigmatize people who continue to mask,” even if it did include exemptions.

“We don’t feel welcome on public transit already,” he said. “Why should I now have to prove to anyone else that I wear a mask because of a medical condition?”

As protests have grown against Israel’s war in Gaza, a younger generation of activists are increasingly obscuring their faces for reasons unrelated to the virus, citing the threat of harassment and retaliation from universities, employers and other sources, as well as the growing use of facial recognition by police.

But officials argue the tactic emboldens bad actors. Earlier this week, a group of protesters — some wearing traditional Palestinian scarves, known as keffiyehs, over their faces — were seen on video asking whether any passengers aboard a crowded subway were Zionists, telling them: “This is your chance to get out.”

In an interview Thursday on CNN, Hochul said the “unacceptable” incident had pushed her to look at restoring the ban on masks.

“You’re sitting on a subway and someone puts on a mask like this and comes in, you don’t know if they’re going to be committing a crime, they’re going to have a gun, or whether they’re just going to be threatening or intimidating you because you are Jewish, which is exactly what happened the other day,” she said.

Still, it’s unclear whether specific passengers on the car were targeted for their religious or political identities.

Long before the pandemic, the statute against mask-wearing had drawn allegations of selective enforcement, sparking a series of legal challenges that argued the law violated the right to anonymous speech.

One of the highest-profile challenges came in 1999, when the Ku Klux Klan sued the city in order to stage a Manhattan rally in their traditional hoods and robes. After a federal judge sided with the Klan, an appeals court reversed the ruling, noting the state’s right to “regulate conduct that it legitimately considers potentially dangerous.”

More recently, supporters of the Russian feminist band Pussy Riot sought to overturn the law after they were arrested for protesting in New York while wearing balaclavas. The city ultimately dropped charges against the protesters, nullifying the lawsuit.

Norman Siegel, a civil rights attorney who represented both the Klan and the Pussy Riot supporters, said Hochul’s attempts to ban masks on public transit could open up another avenue to challenge the law.

“I understand what they’re trying to do, but we have a long history of peaceful protest and anonymous speech,” Siegel said. “There are major First Amendment implications at stake here.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News