‘The only rules? No biting and no eye gouging’: UFC’s first champion Royce Gracie on the night MMA was born

Royce Gracie, the first ever UFC champion and most famous practitioner of jiu-jitsu in the world, slips through the back door of Costa Coffee.

He’s a hard man to get a hold of. I hardly imagined I’d meet him in a coffee chain in Essex, and the peripheral sight of him sat next to me while intently whisking the foam on his Massimo hot chocolate is a little startling. My perception of Gracie as almost mythical implanted images in my mind of him consuming nothing but raw fruit (skin on, of course) and human sweat.

But here he is, still one of the most dangerous men on the planet at 53, clad in a plain black sweatshirt and beanie hat, glad to have left the evening chill outside. His subtle entrance is no attempt to be inconspicuous; his reputation in jiu-jitsu and MMA is essentially unrivalled, but the average Brentwood high-street goer and Costa patron is unlikely to be aware of his stature in those spheres, nor his physical capabilities and heritage.

Gracie’s father, Helio, created Gracie Jiu-Jitsu alongside brother Carlos in their native Brazil in the 1930s, building upon the Japanese origins of the martial art, the first form of which is believed to have surfaced in the 1500s. Jiu-jitsu predominantly involves grappling and seeking submissions – chokes, arm bars, leg locks, among others – though strikes can be utilised at times. As strands of jiu-jitsu go, Gracie’s is as authentic as it gets, and he is the art’s greatest living ambassador.

One of the many reasons for this is his involvement in UFC 1.

No holds barred, no time limits, no judges, no drug tests, bare knuckles, anything goes. The only way to win is by knockout, submission or corner stoppage.

This misconception of modern MMA was the reality at UFC 1 on 12 November 1993 – the first documented ‘mixed martial arts’ event.

“It was hard to find participants to accept the rules,” Gracie tells The Independent. “I remember my brother Rorion and [promoter] Art Davie were going after the No. 1 karate guy and asking him to participate. No. 1 would decline, they would go after No. 2 and so on. For boxing, the same thing.

“A lot of people did not have faith this was gonna go through. It’s illegal to fight on the streets. ‘How are you gonna put this on national TV?’ Everybody was debating about that.

“The night before, when they did the draw out of the hat for who was fighting who, that’s when people started to realise: ‘Oh s***, this thing’s gonna happen! We’re gonna get in a fight tomorrow. What are the rules?’

“There were no rules. ‘Do I need boxing gloves?’ Nope. ‘Do I need shin pads?’ Nope. ‘Everything goes?’ Yep. ‘But what if I kick him in the nuts?’ It’s okay.”

I get the impression none of the above questions were asked by Gracie.

“The only rules were no eye gouging and no biting. So it was very simple.”

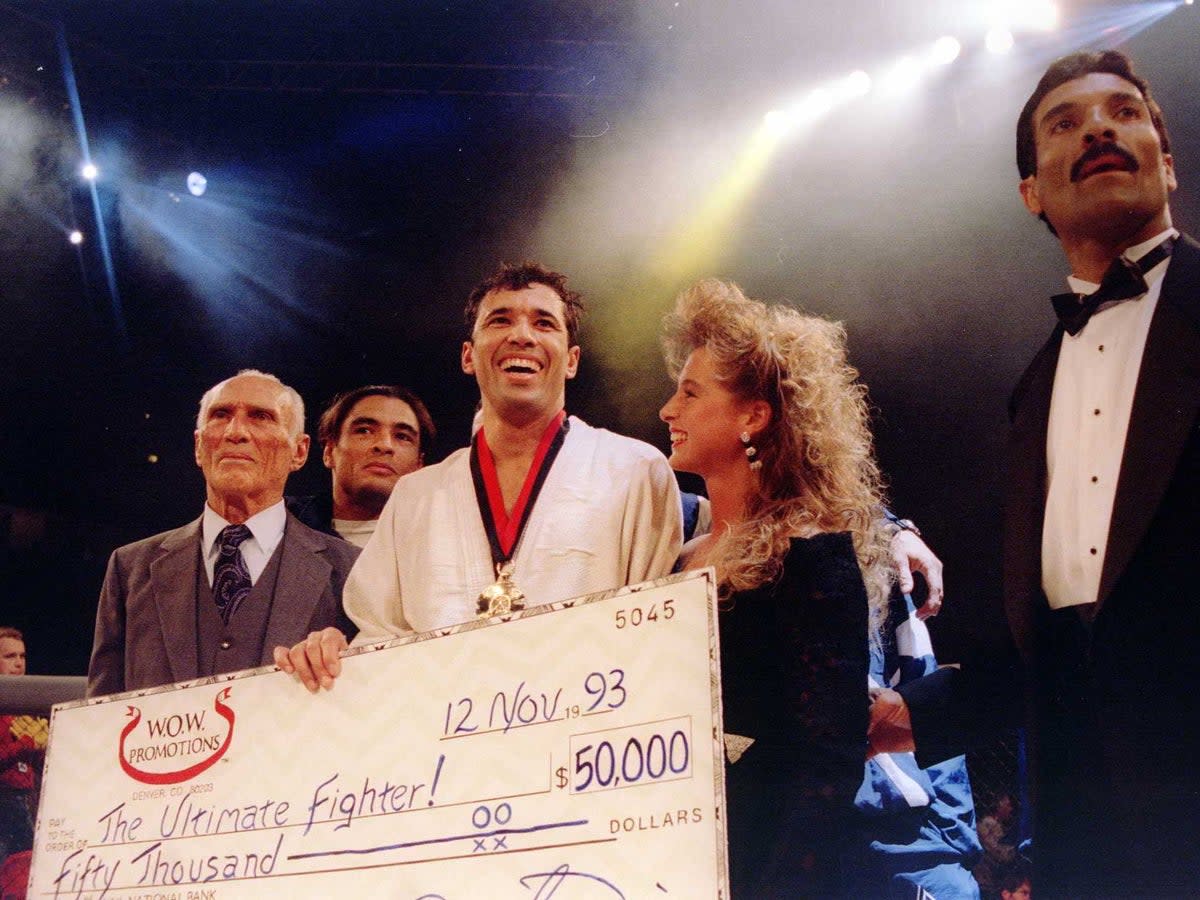

The following night in McNichols Sports Arena in Denver, Colorado, Gracie beat three men consecutively to be crowned the first ever Ultimate Fighting Champion.

First up was Golden Gloves boxing champion Art Jimmerson. Next was future WWE star Ken Shamrock, whose speciality was shootfighting, which combines wrestling and a variation of Kung Fu. Finally, there was Gerard Gordeau, a world champion in Savate – otherwise known as French kickboxing.

With little technology available at the time, a 26-year-old Gracie knew nothing about his opponents beyond their names, faces and records.

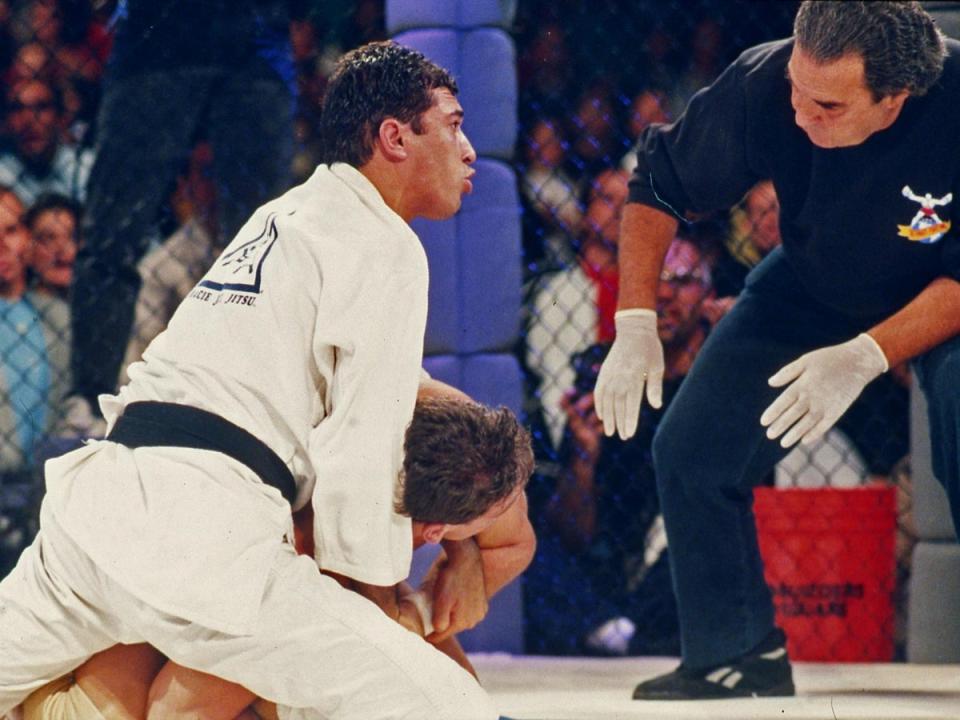

Jimmerson, Shamrock, Gordeau – Gracie submitted them all.

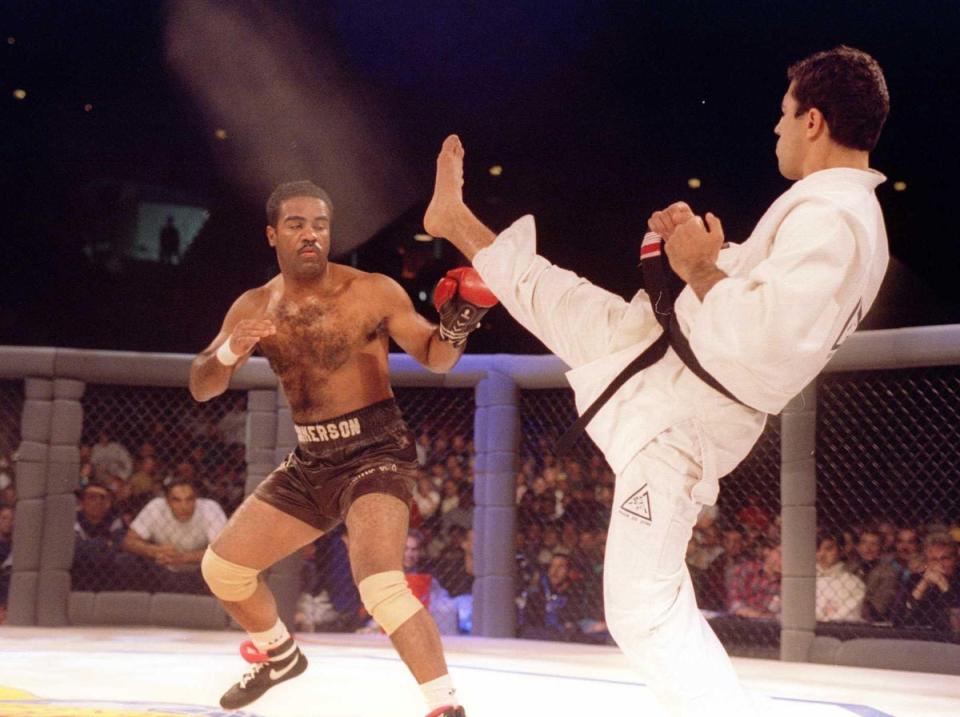

Jimmerson, wearing a boxing glove on his left hand alone so as to expose his power hand, was hesitant from the opening bell as Gracie kept him at bay with side kicks from a southpaw stance. The American threw little and Gracie soon feinted a strike and secured a takedown. Jimmerson was locked in the Brazilian’s clutches, flat on his back, smothered and choked. All in all, he lasted just over two minutes.

Shamrock did not reach the one-minute mark. Gordeau almost survived two minutes in the Octagon with Gracie, but inevitably submitted to a choke, just like Jimmerson and Shamrock.

The four minutes and 19 seconds the slender Gracie spent in the ring that evening, sporting a traditional white gi, defeating bigger men, amounted to a captivating showcase of the effectiveness of jiu-jitsu.

That was almost what the event was designed to be. Gracie had previously answered the challenges of local martial artists from different disciplines in garages, and the plan was to take those contests to the biggest stage possible in America.

“My father, my uncles, my cousins, my brothers had been doing these kinds of challenges in Brazil before, in big stadiums,” says Gracie, whose accent and intonation make him sound like a Brazilian Arnold Schwarzenegger – rather fitting for a real life Terminator.

“The garage challenges were just a smaller scale and for us to gain students, not to hurt the guys. We wanted to turn that person and their coach into a student.

“Then the first UFC…” Gracie raises his gaze to a distant corner of the cafe ceiling. Arm outstretched, index finger extended, he draws an arc, following it by panning his vision from left to right. “The first UFC was to show the crowd that they can be my students.” For a moment I can see the 7,800 in attendance in Denver on that November night in 1993. I can even hear them over the smooth jazz slinking through this Essex Costa.

Despite three faultless performances from Gracie that evening, he barely bothered to celebrate. “Just another day.”

What was just another day for Gracie was the most important day in MMA history.

MMA in UFC 1 meant mixing martial artists from various disciplines in one competition. Now, it means each fighter must be proficient in a mixture of martial arts.

While the MMA on display at UFC 1 may seem novel in comparison to today’s streamlined evolution, the entertainment factor has persisted throughout the sport’s lifespan. It’s something Gracie could live without.

“They feel they have to insult everybody to sell seats,” Gracie says. “But they don’t have to lose respect. There’s a very fine line that people sometimes cross. It’s easier to be hated than be a good fighter and likeable.”

Jiu-jitsu, like most martial arts, has a history much deeper than the sport of MMA, and is thus less moveable. Many would expect there’s not much left for Gracie to learn.

“I’m always learning,” he counters, as swiftly as if we were sparring. “Right now I’m learning a lot as a teacher.

“Most people don’t even know why they are learning a martial art. ‘Because I want to get fit, because I want to compete.’ Na, it’s none of that.

“It’s because… they don’t know it, but something happened to them, and that stays far in the back of your head. Or they saw something happen to someone and wouldn’t have the confidence to deal with the situation. They’re thinking: ‘Man, what if that was me?’

“We teach self-defence – not for tournament points, not to be a professional fighter. Just in case somebody comes up and talks to you in a certain way, you can reply with confidence, you can stand your ground.”

Someone who benefited first-hand from Gracie’s teachings is Jon Hegan, one of just five Gracie Jiu-Jitsu black belts in the United Kingdom. After training under Gracie in Los Angeles in the late 1990s, Hegan would develop a deep commitment to jiu-jitsu and loyalty to the UFC legend, passing through the ranks – from white belt to blue, from blue to purple, from purple to brown, leaving him with the ultimate task of testing for his black belt in Miami.

Following an initial “crushing” failure, Hegan returned a year later and succeeded.

“They say there’s three per cent – that’s the number that go from white belt to black belt,” Hegan tells The Independent. He’s in that three per cent, but suggests without a hint of irony: “I still don’t know much.”

He certainly knows enough to teach Gracie Jiu-Jitsu at The Jon Hegan Academy, which Gracie visits annually to teach a seminar.

Gracie also still trains, as does most of his family, but he retired from MMA in… well, it’s hard to say.

“I retired 10 years ago, man, but they keep dragging me back in,” he says.

My son has now come up with the idea that him and I should fight on the same card! I was like: ‘Dude, I’m old, I don’t wanna fight anymore.’ He said: ‘You’ve got to.’ I don’t know about that…”

Following UFC 1, Gracie rematched Shamrock in a bout that clocked in at 36 minutes as the longest contest in UFC history. Both men later entered the Pioneer Wing of the UFC’s Hall of Fame. There was even a trilogy fight in 2016 under the Bellator banner, with Gracie winning by TKO.

Gracie also competed in Japanese promotion Pride and returned to UFC throughout his illustrious career, in which he also defeated renowned sumo wrestler Akebono in an MMA contest. Retired or not, the Brazilian’s record stands at 15-2-3.

The word pioneer is flung around as flippantly as Gracie’s opponents, but undoubtedly applies to the Brazilian, without whom MMA in its current form would likely never have existed, nor the sport’s flagship promotion, UFC.

For fans worldwide, UFC 1 was the birth of a sport. For Gracie?

“Just another day.”

N.B. Article first published in 2019.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News