Opinion: After ‘Shaft,’ Black Americans in film were never portrayed the same way

Editor’s note: Sam Fulwood III is a writer and veteran news correspondent. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. Read more opinion at CNN.

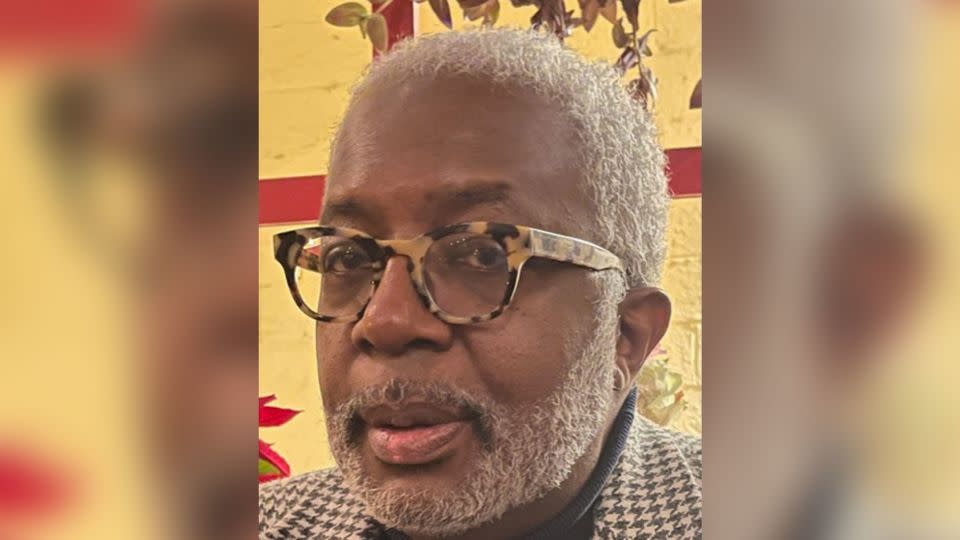

In the 1971 film “Shaft,” Richard Roundtree — who died this week at 81 — strutted, cussed and loved his way across New York, from Greenwich Village through Times Square and all over Harlem, embodying the legendary movie character so perfectly that the actor and the fictional private detective would come to be seen as one in the same.

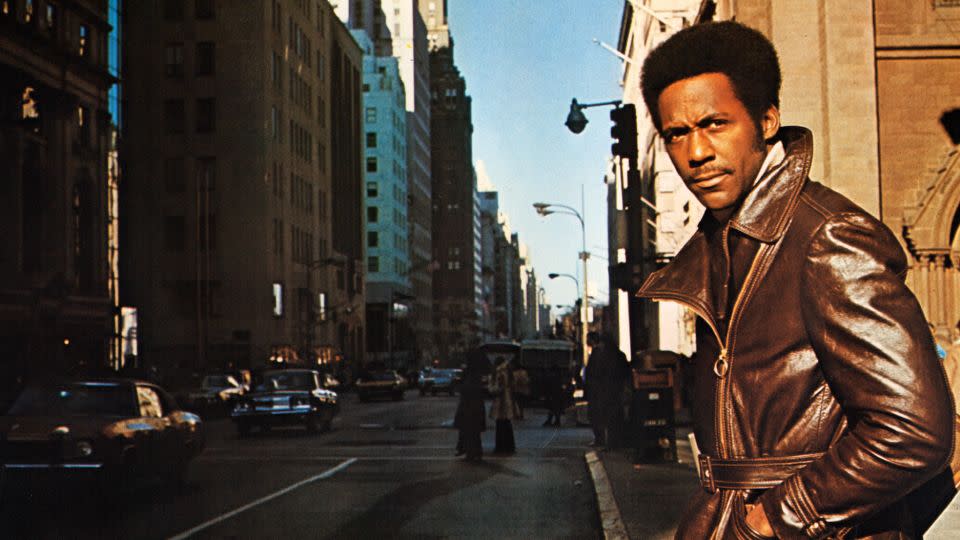

It was a movie that grabbed one by the lapels from its opening scene: Roundtree as John Shaft gives a middle finger to a White cab driver as he illegally crosses a busy New York City intersection.

It set the stage for as nontraditional a narrative as had ever been shown in US movie theaters, given the depiction until that time of Black men as mild-mannered — even servile —on the rare occasions when they were shown on screen at all.

The image of the Black male in the popular imagination changed dramatically after “Shaft.” Even today, the contemporary representation of Black masculinity is synonymous with Roundtree’s portrayal of the fictitious private investigator.

Roundtree as Shaft was the exemplar, perhaps even the progenitor, of a certain Black male style which later came to be known colloquially as “swag.” Any number of Black men who occupy the public stage today can trace their lineage — culturally speaking at least — to Roundtree’s unforgettable performance. Think Samuel L. Jackson. Will Smith. Denzel Washington. Idris Elba.

Based on a pulp novel by The New York Times reporter-turned novelist Ernest Tidyman, a White man, Shaft was written in the hard-boiled, Sam Spade-type detective style. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), at the time a struggling entertainment conglomerate, took a gamble in buying Tidyman’s screenplay and hiring famed Black photographer Gordon Parks to direct the movie. The bet paid off handsomely: The film earned $12 million in ticket sales off of a $500,000 production budget, which helped the studio avoid bankruptcy.

Roundtree gave life to the never-before-seen, on-screen alchemy of arrogance and attitude, confidence and charisma, swagger and sexuality in a dark-skinned African American man. With an almost entirely Black cast and a Black director, “Shaft” was a watershed film born of a specific political and social moment: Malcolm X had been gunned down about a half-decade earlier in the Audubon Ballroom, not far from where scenes from the movie were filmed. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination had occurred just a few years prior. With its 1971 cinematic release, Shaft stood as a cultural touchstone, a perfect storm of racial resistance and old-fashioned Hollywood myth-building — a triumphant and defiant celebration of Blackness.

The Academy Award-winning soundtrack for Shaft was as much a character in the film as any of its multitude of Black actors. Who, in memorializing and mourning Roundtree’s death, can avoid launching into a refrain from the title track that heralded the actor as “a sex machine to all the chicks” and “a complicated man, but no one understands him like his woman”?

And who can forget the hi-hat cymbals and the thumping wah-wah guitar riff? “You’ve got to capture the essence of the character of Shaft. He’s always on the move, roving, prowling,” Isaac Hayes once said, describing his objective in composing his enigmatic score. No soundtrack has ever captured a movie’s protagonist better.

Equally iconic were Roundtree’s wardrobe choices: “Shaft” spawned a decade-long fashion fascination by Black men for knee-length leather coats, turtleneck sweaters and crotch-grabbing tight pants. Those fashion choices even made a cameo appearance in the walk-off scene of the last “Shaft” film (2019) that brought Roundtree back in his eponymous role, with actor Samuel L. Jackson playing his son and Jessie T. Usher his grandson.

The movie also introduced the world broadly to the “blaxploitation” film, and at the moment of his death, Roundtree was still its exemplar. But “Shaft” wasn’t the first such film. That honor goes to Melvin Van Peebles’ 1971 “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” which was released a few months ahead of “Shaft” but isn’t as well remembered, in part because of its limited theatrical release. By contrast, “Shaft” — a huge box office hit — single-handedly ushered the genre into existence with its low budget and high box office receipts and an attitude that was always unapologetically Black.

Parks, one of the pre-eminent still photographers of his time, embraced the opportunity to make a movie where the Black character was a sassy-mouthed, gun-toting Black man who didn’t sacrifice himself to save White people. MGM leaned into this angle, hiring the African-American-owned UniWorld advertising agency to create a campaign targeted primarily to young Black, inner-city audiences, noting that “Shaft” “has fun at the expense of the (White) establishment.”

When “Shaft” flashed across the screen in darkened movie houses, the era of blaxploitation soared, giving birth to a succession of copycat films that led to a Golden Age for Black actors. Hopping on board for a self-affirming ride, Black American men found their hero who, as the song said, was “a bad mother (shut your mouth!) … But I’m talking about Shaft!”

The movie marked a breakthrough for Blacks in Hollywood who until then had little hope of ever seeing their names crawl up the screen during the closing credits for anything other than a supporting role, if that.

It was Richard Roundtree — John Shaft — who changed all that.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com

Yahoo News

Yahoo News