Opinion: Why antisemitism and anti-Zionism are so deeply intertwined

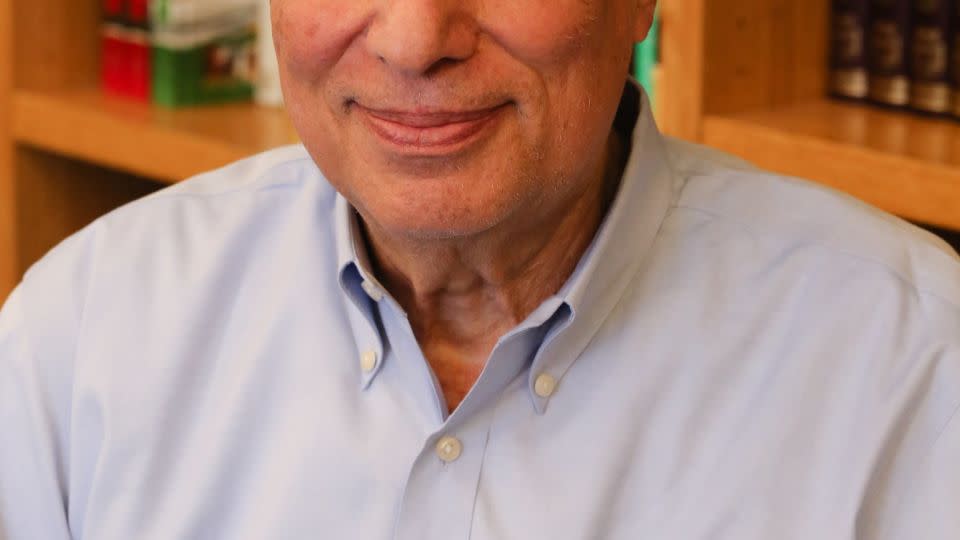

Editor’s Note: Avi Weiss is the founding rabbi of the Hebrew institute of Riverdale-the Bayit and founder and co-founder, respectively, of the Yeshivat Chovevei Torah and Yeshivat Maharat rabbinical schools. His new thematic commentary on the Bible, “Torat Ahavah – Loving Torah,” has just been published. The views expressed here are the author’s own. Read more opinion on CNN.

Approaching my 80th birthday, I realize that as a Jew, I’ve lived a honeymoon life. Born at the tail end of World War II, I grew up with antisemitism by and large under control, as even vicious Jew haters were reticent to attack Jews. To some extent, I believe, the world’s guilt over either its complicity or inactivity as 6 million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust silenced the enemies of our people.

This doesn’t mean anti-Semitism was not a serious problem, especially in recent decades. There were vicious antisemites and horrific antisemitic incidents that had to be condemned. The likes of Louis Farrakhan and David Duke needed to be confronted head on. Events like the 1991 murder of Yankel Rosenbaum, a Hasidic Lubavitch scholar stabbed to death by a Jew-hating mob, brought fear into the hearts and souls of the Jewish community. Still, antisemitism was not endemic.

Eight decades after the Holocaust, however, the Shoah is in the rearview mirror. For much of the world, it is a footnote in history. Its memory no longer stymies antisemites, who were always hiding in the shadows and have now surfaced with fury.

The holiday of Purim, celebrated by Jews around the world this weekend, commemorates a story in the Bible’s Book of Esther when the whole of the Jewish community in ancient Persia was threatened with extinction by the King’s adviser Haman and his cohorts.

The story touches upon dimensions of antisemitism that were pungent back then, and have remained powerful and threatening across thousands of years. These forms of hatred of Jews past and present fall into three categories shaping the foundations of a nation: people, ideology and land. We have seen all of them in modern times.

During the Holocaust the goal of the Third Reich was the genocide of the Jewish people; that is, murdering Jews because they were Jews. It was the same agenda that motivated Haman two millennia ago.

During the Cold War, Soviet antisemitism came to the fore with a vengeance after the Second World War. It was based on loathing Jewish faith and ideology. Like Haman, the USSR’s leaders saw our Jewish culture and religious practices as alien to their state. Believing Judaism contrary to their Marxist view of the world, the Soviets didn’t allow Jews to live a Jewish life. Those who wished to emigrate were held as quasi-hostages behind the Iron Curtain.

Today, antisemitism is often expressed by denying that Jews have the right to be sovereign in their own land. Yet, without sovereignty, there can be no security. Jews will forever be vulnerable to the next Haman to come along. Throughout the millennia, as a stateless people, Jews were subject to persecution, discrimination and expulsion. This is a historical reality that anti-Zionists conveniently ignore when they say they are not against Jews, just against Jews having their own state.

They, and the world at large, also have no problem with having Muslim states, several of them explicitly defined as Islamic or Arab. However, the concept of one tiny Jewish state, the only Western-style democracy in the Middle East, is constantly rejected and attacked.

Statehood is built into Jewish consciousness. Israel is more than just a place where Jews can be free and safe. As Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, the first Ashkenazic chief rabbi of pre-state Israel said: Israel is not external to Judaism but inherently part of Jewish consciousness. To wit: Jews across the religious denominations pray for the return to Zion in their daily liturgy. And religious or not, the vast majority of Jews feel inextricably, soulfully bound to Israel and describe themselves as Zionists.

So while anti-Zionists defend themselves by claiming they are not anti-Semites, when anti-Zionists declare “no Zionists allowed,” they are actually saying, “No Jews allowed.” The fact that so many anti-Israel demonstrations are targeting Jewish rather than Israeli institutions underscores this dynamic.

The interfacing of anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism was never more apparent than on October 7. The goal of Hamas, like their antecedent Haman, goes beyond destroying Israel; its mission – as articulated in the founding Hamas charter – is to kill as many Jews as possible. Jews worldwide felt personally attacked that day, understanding that if Hamas could, each and every Jew would have been murdered.

This doesn’t mean that every anti-Zionist is an anti-Semite. There are always exceptions to a rule. But the exception doesn’t void the rule. It’s one thing to disagree, even vehemently, with some core Israeli policies. But anti-Zionism goes well beyond that to object to the very notion of Jewish self-determination, and thereby target 7 million Jews, half of the world’s Jewish population who are now living in Zion, and many thousands more who yearn to make “aliya,” or move home to Israel.

Indeed, Zionism is a play on the Hebrew word “tziun-metzuyan,” meaning a stamp of excellence. It is there in Israel that all Israelis living in a sovereign nation have the potential to do their humble share to make this world a better place.

Purim is the story of a vulnerable, powerless Jewish people living in the diaspora threatened with physical and spiritual annihilation. Its unwritten message is the necessity for Jews to be Zionist, to live in Zion, to have a homeland wherein it is in their power to protect themselves with strength, and what Israel’s army calls the “purity of arms.”

According to the Book of Esther, the Jews in ancient Persia were ultimately saved by the grace of the king. But the State of Israel, with the benevolence of God, allows Jews to save themselves.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com

Yahoo News

Yahoo News