Pakistan’s choice at election today: The lion, the millennial or the cricketer

Pakistan is set for a heated three-way race, amid an election atmosphere that has never been more polarised after the flurry of new criminal convictions handed to the candidate who might otherwise have been analysts’ favourite.

In a political landscape dominated by big personalities, jailed former prime minister Imran Khan’s name won’t be on any ballot paper, and his PTI party has been forced to back a list of so-called independent candidates rather than compete under its own iconic cricket bat symbol.

With PTI hamstrung by a police crackdown, the most likely winners are seen as the ruling Pakistan Muslim League – Nawaz (PML-N) party of another former prime minister, Nawaz Sharif. After his own jail spell and exile, Sharif – dubbed the “Lion of Punjab” – is back in Islamabad and fronting political rallies where supporters carry soft toys of the big cat as well as tigers, the party’s symbol.

Completing the trio of men vying to become prime minister is Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, the 35-year-old son of Pakistan’s first female leader Benazir Bhutto. Despite being the face of the legacy Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), he has pitched himself as the outsider who can offer a way out of the political turmoil of recent years, while also tackling issues that matter to young people in Pakistan, such as the climate crisis and youth unemployment.

The ruling party will need to command at least half of the 226 National Assembly seats up for grabs. For Sheraz Khan in Lahore, the uncertainty gripping the nation ahead of the 8 February election is palpable on the streets. Although 51 years old, he plans to cast his vote for the first time in a general election this Thursday.

“I am looking forward to it,” he tells The Independent. “I searched instructions on the web for casting my vote. One of the things I’m noticing this time around, [is that] there’s uncertainty given the polarised climate.”

Plenty of voters like Sheraz Khan are drawn to the lure of the more experienced leader in Sharif, who is also seen as having the implicit backing of the country’s powerful military establishment. It would be the pragmatic choice for those who accept the outsize role the military plays in choosing who comes to power in the country, and avoiding the kind of chaos that accompanied Imran Khan’s 2022 ousting. Khan has accused the military of conspiring with foreign powers including the US to get rid of him with a parliamentary vote of no confidence.

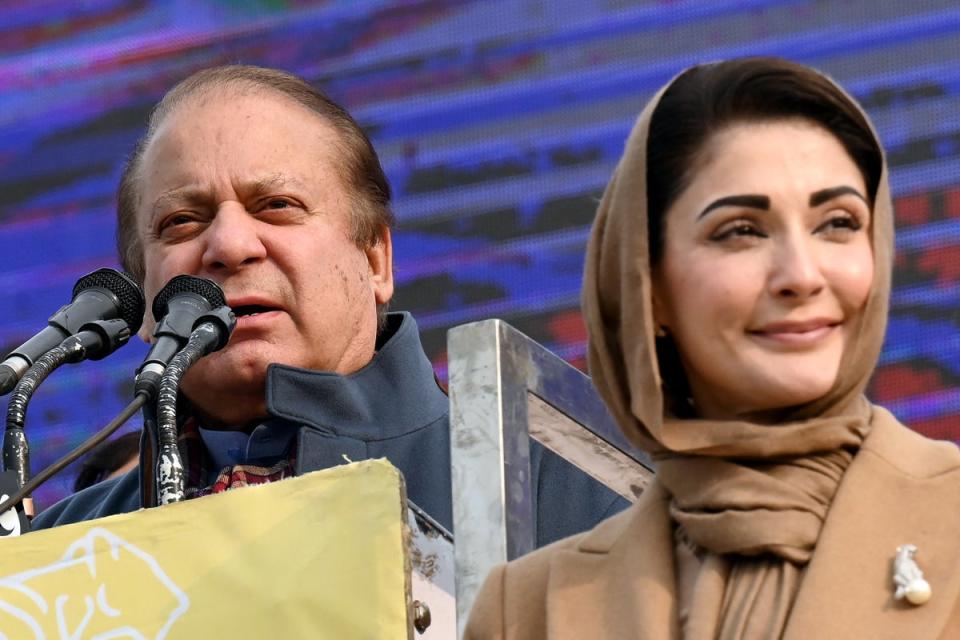

Sharif and his daughter, Maryam Nawaz, who is also a senior figure for PML-N, addressed a huge crowd during a campaign rally at Mansehra in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province last month, with Maryam urging them to make the right choice at the ballot box as “sensible” people.

The party is offering to bring stability and fix Pakistan’s economic troubles, accusing the Imran Khan administration of wrecking the country’s finances and forcing it to seek a bailout deal from the International Monetary Fund to avoid a catastrophic default.

“I am shifting my loyalty this time, which is unique in Pakistan where people don’t generally switch their loyalty for their political heroes. The long stint of PML-N in the Punjab constituency has had an impact on the lives of people which I’ve seen through my work-related travel. I have a snapshot. Corruption is much lower here,” Sheraz Khan says.

The party he is switching from is not PTI but the PPP of the Bhutto family – he says he used to sympathise with the party when its two leaders were jailed in the 1990s.

Perhaps Sheraz Khan is no longer the PPP’s target voter. Former foreign minister Bhutto Zardari has openly aimed his campaign messaging at the two-thirds of Pakistan’s 240 million population who are under the age of 30, hoping they can help him become the youngest prime minister in the country’s history.

The Oxford-educated and Western suit-wearing Bhutto Zardari is less than half the age of his primary opponent Sharif, 74.

“Look around, who are the majority of young people in Pakistan now? Bilawal Bhutto Zardari is a young leader who understands the problems of young people and has no desire for revenge, so our party is liked by the majority of young people,” Syad Jawad Hamdani, a PPP party worker, tells The Independent.

Bhutto Zardari is walking in the footsteps of his mother – who was also Oxford-educated and in the 1990s came head-to-head with Nawaz Sharif herself – and will bring Pakistan greater clout on the world stage, the party worker says.

“God willing, on 8 February the Pakistan People’s Party will come to power with the majority of the people’s votes,” he says.

Neither of these leaders invokes the same levels of passion as cricket legend-turned-politician Imran Khan, who had already been jailed for corruption and barred from holding public office before he was hit by a wave of new convictions in the past week, including breaching the state secrets act and the country’s marriage laws.

Khan and his party have been using AI and virtual rallies to get around what they describe as systematic discrimination by the police against any overt display of support for PTI, yet even these have been disrupted by complete government shutdowns of the internet when the rallies are due to take place.

Party worker Abid Khan in Karachi bemoans the extraordinary restrictions preventing PTI from campaigning, including the fact that more than 6,000 volunteers and officials like him have been arrested or detained in the past two weeks alone.

“We’re all in unknown locations, have not seen our families in days in order to escape getting arrested by Pakistan police. The leaders, mere puppets in the hand of the military, have one mission – jail all senior leaders of PTI and keep them away from elections,” says Abid Khan.

The government says Imran Khan and the party leadership are responsible for the widespread unrest that followed his first arrest on 9 May last year, which included attacks on facilities and homes associated with the country’s military. It denies carrying out a targeted political crackdown on the party and says criminal charges stem from that period of unrest, as well as other offences.

The party argues that the timing and diverse nature of the convictions against Imran Khan last week show they are blatantly politically motivated.

“If they let our Khan saab play fairly, he will come back with a sweeping victory. They know he is their biggest opponent so they have used every trick in the book to keep him away from millions of Pakistanis who love him. Insha’Allah, 8 February will tell us how much he is loved,” he tells The Independent.

PTI spokesperson Muzzammil Aslam says Khan is not just going after the sympathy vote. He says the economy was showing signs of improvement before the party was removed from power in 2022 and that it should be allowed to finish the work it started.

“The decision to bring him back makes sense economically. Our economy is not stable, our debt-risk is high at the moment. Any slippage from here will cost us a big economic setback, we will struggle to meet our debt obligations. This requires political stability at the centre of administration which is not guaranteed by any other party but PTI and Mr Khan,” he says.

He is adamant that opinion polling still showed PTI garnering more than 50 per cent of public support and that, in spite of all its legal setbacks, the party has managed to put up or back 260 candidates, enough to retake control of parliament and overturn PTI’s fortunes.

Many question whether PTI would be allowed back into power even if these candidates win enough votes, however, voicing scepticism over the robustness of the election in the face of potential interference from the military.

Amna Kausar, the manager and curator of the country’s first-ever Young Politicians’ Fellowship Programme run by the PILDAT pro-democracy think tank, says she is seeing high levels of dejection over the elections among the first-time voters she interacts with.

“Lots of questions have been raised now at Pakistan’s pre-poll environment, with many candidates [like PTI] not being given any level-playing field. We’ve been called an electoral autocracy over the recent events in the country.

“A student asked why they should vote when the results are ultimately at the mercy of a handful [in the establishment],” she says, adding that the three male legacy figures in the race have done little to help that perception. “There are systemic barriers for including women in the elections, young students are demanding a students’ union. There’s no inclusivity of youth leaders,” she says.

Kausar says turnout will be a key metric to determine whether voters in Pakistan believe this election will bring about real change in the country, or whether – regardless of which of the three men enters office – it is set to repeat the familiar cycle of economic brinkmanship and political fragility.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News