How a pan-European picnic brought down the iron curtain

When the end finally came for the iron curtain, it was not bulldozers or hammers that struck one of the first decisive blows, but a picnic.

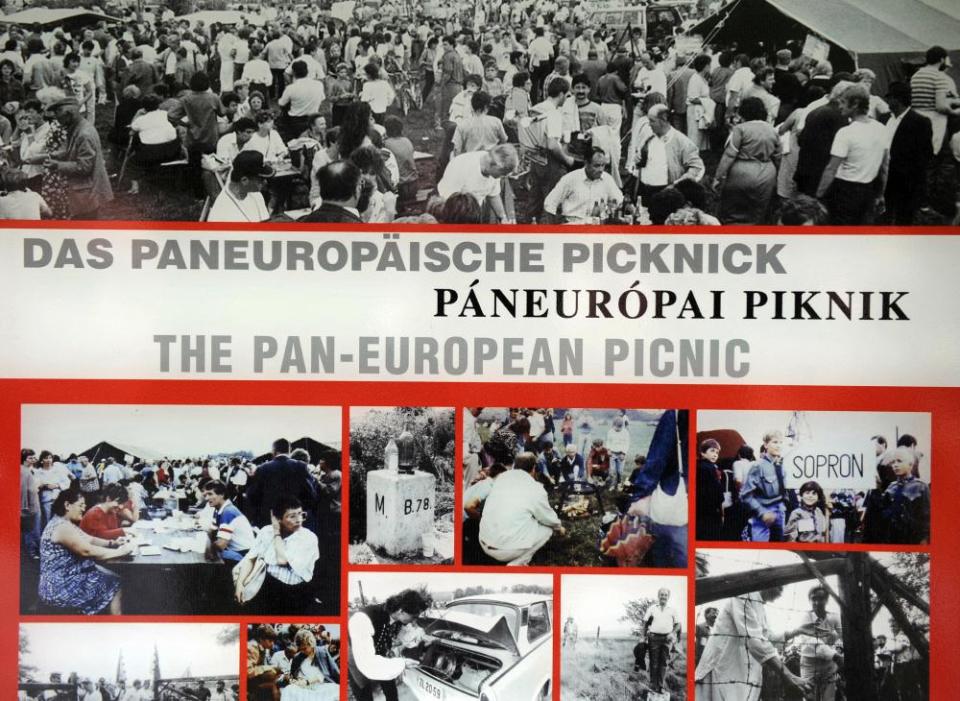

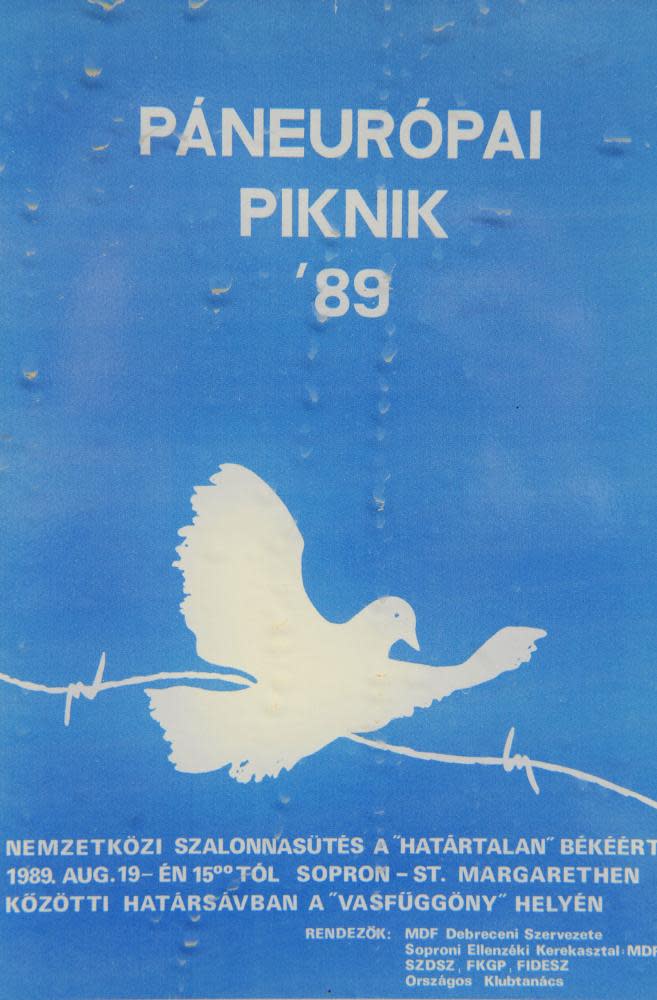

Thirty years ago this Monday, on 19 August 1989, thousands of Hungarians and Austrians gathered at the border fence between the two countries, which also marked the dividing line between the Communist bloc and the west. They had come for a “pan-European picnic” of solidarity and friendship across the iron curtain, as momentum for political change increased and the eastern bloc regimes struggled to keep up with rising popular discontent.

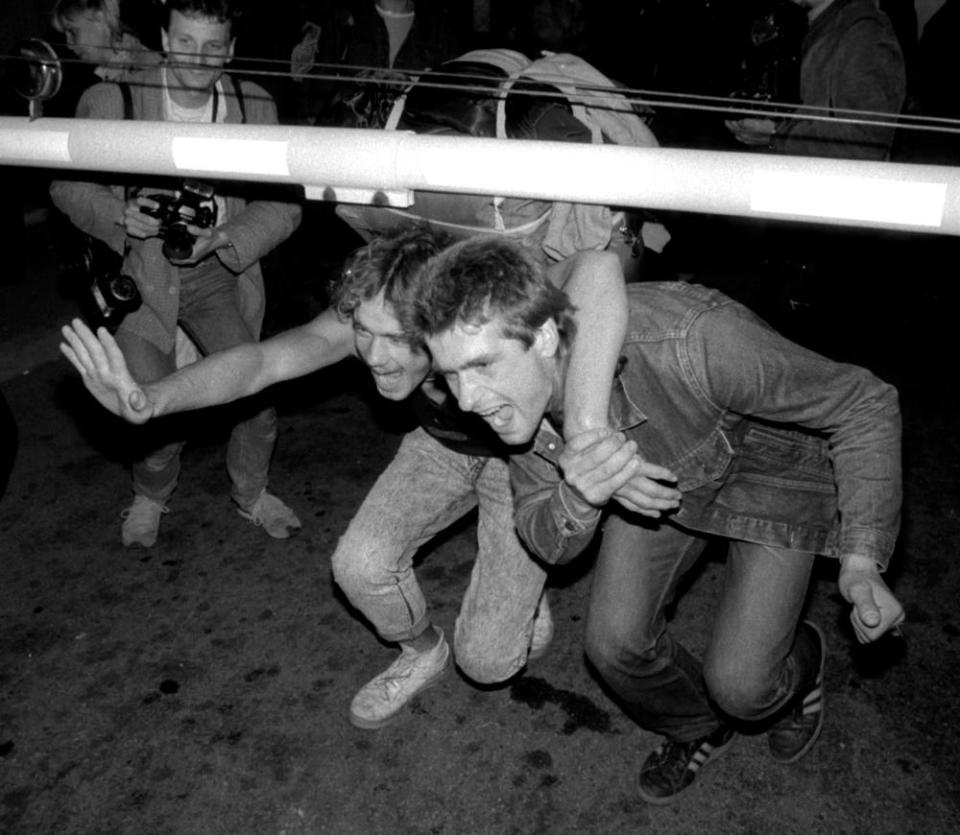

They were joined by hundreds of East Germans who took the opportunity to rush across the border into Austria and from there to West Germany. Hungarian border guards declined to shoot, and in the subsequent weeks thousands more made the crossing. Three months later the Berlin Wall fell and the path to the end of communism in Europe and the continent’s unification was irreversible.

On Monday the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, will travel to Sopron, a Hungarian town near the border, to mark the event together with Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orbán. Merkel, born in East Germany, has spoken repeatedly about the importance for her personally of the fall of the wall and the events leading up to it.

Thirty years after the opening of the border and the tearing down of the fence, it is hard not to view the symbolism of the event through the lens of the present. Merkel has been outspoken against present-day walls, both real and metaphorical, using a Harvard University commencement address this year to call on people to “tear down walls of ignorance and narrow-mindedness”, a thinly veiled rebuke of Donald Trump’s politics.

Orbán, meanwhile, is the European champion of modern-day walls, having built his popularity in Hungary on promising to keep refugees and migrants from Africa and the Middle East out of Europe. His government constructed a fence along the country’s southern border with Serbia after hundreds of thousands of people crossed Hungary in 2015, many of them with Merkel’s Germany as their final destination.

Orbán’s media empire railed against Merkel’s decision in 2015 to extend a welcome to those fleeing war, and he has been the most extreme of the many anti-migration politicians in central Europe, warning of a Muslim “invasion” of Europe and calling for strongly guarded borders.

It is a far cry from a declaration made at the time of the picnic, calling for “the demolition of barbed wires and cultural barriers raised by political chicanery” to achieve worldwide peace. But for the Hungarians who organised the picnic three decades ago, comparisons between the two border walls are misguided and offensive.

“The iron curtain was built to imprison us, the fence in 2015 was built to protect us by a democratically elected government,” said László Nagy, of the Pan-European Picnic Foundation. He spoke of disappointment about the criticism of Orbán’s government from western Europe, and put it down to a patronising attitude among western Europeans, who he said had betrayed Hungary and other central European countries after the fall of communism and did not understand the region’s history.

In a recent interview with a Hungarian magazine, László Magas, the main organiser of the picnic in Sopron and now a local councillor for Orbán’s Fidesz party, said that during trips to western Europe in the 1980s he had envied the tranquility and affluence of life, but he was now less impressed with life further west.

He recalled a recent trip to France and Germany during which he had been horrified to encounter gender-neutral toilets and homosexual couples, and quoted German friends he stayed with, dismayed at the prospect of migrants from Africa being housed in their village: “You’re lucky to have a prime minister like Viktor Orbán!” they told him.

Whatever people’s attitudes to today’s wave of people fleeing oppression, EU membership remains popular in Hungary, and there is no doubt that for a whole generation of Hungarians the events of August 1989 remain a defining memory on the path to liberation.

“After the war we were closed in a box for decades. Opening the border gave us back the freedom we didn’t have for so long,” said Ditte Preznánszky, who was a 22-year-old languages student in Budapest in 1989, and travelled to the picnic on a bus arranged by a student summer camp she was attending.

The Hungarian government of the time, which had taken steps to start dismantling parts of the border fence several months earlier, gave official blessing to the picnic, and thousands of Austrians came across the border to join the Hungarians for an afternoon of music and speeches. Pliers were handed out and people set about dismantling the fence, which until not long before had been electrified.

“I had an uncle who escaped in 1956 and most of us knew the terrible things that had happened on the border, so it was very exciting to cut down the iron curtain,” said Preznánszky.

The organisers insist they had not banked on the arrival of hundreds of East Germans, who were allowed to holiday in Hungary but not to travel to the west. Still, tipped off by West German diplomats in the country, several hundred travelled to Sopron and burst through the border gate and into Austria. The guards on duty decided not to shoot, and although the border crossing was resealed a day later, the tide had turned. Overcoming worries of how Moscow would react, Hungary’s government opened the border properly on 11 September and tens of thousands of East Germans passed through.

Nowadays there is heavy traffic in both directions across the border. Sopron has found a niche in dental tourism, with Germans and Austrians travelling to the town to receive cut-price treatment, while thousands of Hungarians go the other way in search of higher salaries.

The border post was removed when Hungary joined the European Union’s Schengen zone in 2007, but Austrian border guards reappeared in 2015 during the migration crisis and have remained in place. “They’re there, but they will only stop you if you’re brown. They’re racist but nobody cares, you in the west only care about harassing Hungary for being racist because we are the doormat of Europe,” said Nagy.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News