Pete Townshend on AI, Roger Daltrey, and Finishing The Who’s Great Lost Masterpiece

Who’s Next is one of the greatest rock ’n’ roll albums, a record of The Who at the peak of their considerable powers.

Sure, My Generation may have been the first punk album—a decade and a half ahead of its time—and The Who Sell Out helped redefine the album as an artform. Then, of course, there was Tommy, which broke the band as international superstars, and Quadrophenia, which was a constant on the turntables of disaffected teens everywhere in the 1970s and ’80s, counting Eddie Vedder, Scott Weiland, and so many proto rock stars (and me!) as disciples.

No, 1971’s Who’s Next is The Who album that has always, and probably will always, define the band. “I don’t think we’ve done a show since the ’70s that didn’t include at least three or four songs from it,” Pete Townshend, the band’s guiding force, says today.

But Who’s Next is also the Who album that almost wasn’t.

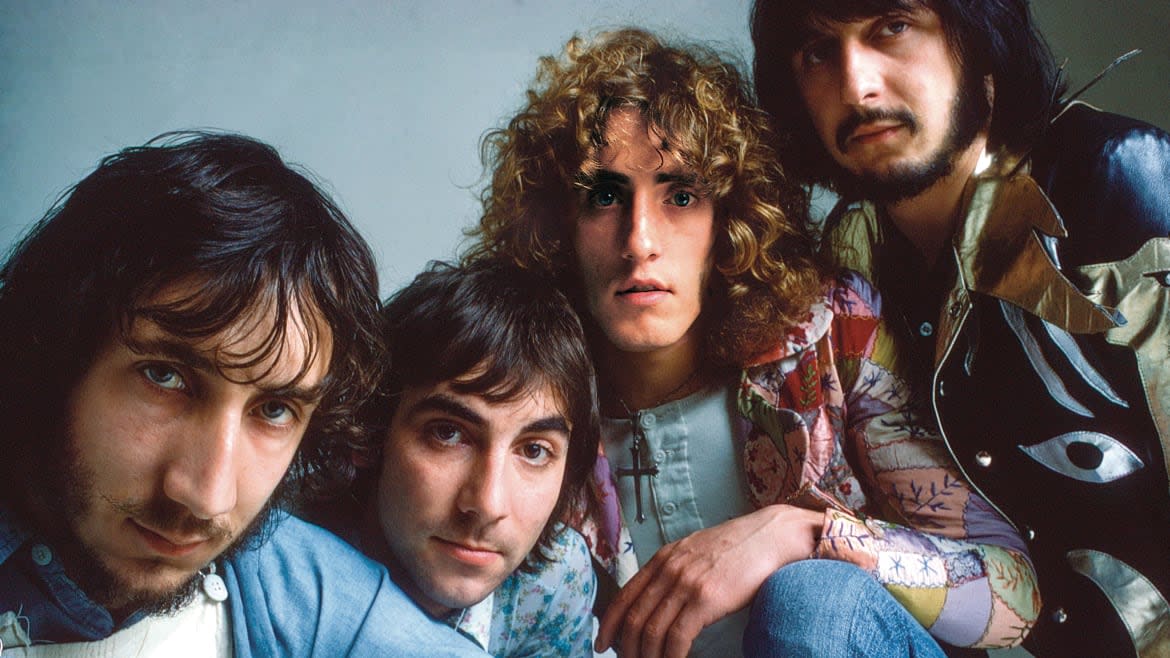

The Who

With his bandmates and management (who also ran The Who’s record label) champing at the bit for a big, bold follow-up to 1969’s worldwide smash Tommy, Townshend, in between dates on a relentless touring schedule, dug in at his home studio—a luxury that was unheard of at the time and that “rivaled Abbey Road, technically,” he says. There, he started expanding his songwriting palette via the latest synthesizer technology.

The results? Life House, the epic, never-completed, rock-opera concept album that ended up inspiring Who’s Next, and that has been something of a white whale for Townshend for years.

Along with some of the best songs Townshend had ever written—“Baba O'Riley,” “Behind Blue Eyes,” “Bargain,” “Going Mobile,” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again” would all end up on Who’s Next; “Naked Eye,” “Pure and Easy,” “Too Much of Anything,” and a host of others would trickle out during the era—over a couple of days in September 1970, he also wrote a futuristic script that foretells a planet on the verge of ecological collapse, with a population locked into virtual reality suits controlled by autocratic rulers and pacified by an endless stream of mind-numbing content.

While that may sound pretty easily digestible—if not downright prescient—today, even in the wake of the moon landing and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Townshend drew quizzical blanks from just about everyone he vainly tried to get on board. The fact that the plot twist came in the guise of rock ’n’ roll being outlawed, leading to a revolt at the Life House, where music had allowed masses of people to congregate and merge into a single, universal mind, didn’t help matters.

More than 50 years later, Townshend, 78, is in some ways still chasing his dream of the Life House project, as proven by a massive new 11-disc box set, which comes complete with a remastered version of Who’s Next, loads of Who tracks, and a raft of home demos from the era. It also includes a book by Townshend and Who experts Andy Neil and Matt Kent, plus a graphic novel expanding the story of Life House.

Along the way, Life House was never far from Townshend’s mind. He nearly had a nervous breakdown during the early days of the project, coming frighteningly close to jumping out the window of the Manhattan hotel suite of one of his then-managers and most ardent supporters, Kit Lambert. Then, after abandoning the Life House project in favor of the more traditional, nine-song Who’s Next album at producer Glyn Johns’ urging, Townshend enlisted The Who’s frontman, Roger Daltrey, to revisit the Life House script. Townshend even fleshed out and updated the story with songs like “Slip Kid,” “Who Are You,” and “Sister Disco,” which would go on to become Who staples, before ultimately giving up again.

Finally, at the turn of the century, he released The Lifehouse Chronicles box set on his own Eel Pie label—which included home demos and even a radio play of Life House, plus a book—and performed two shows at Sadler’s Wells in London that once and for all put the pieces of his ambitious work into a cohesive narrative.

Still, like Brian Wilson’s aborted SMiLE and so many other “great, lost rock albums,” Life House was really more an idea in Townshend’s head than anything else. That is, until now.

The last time I talked to you properly, you teased this project. You talked about choosing the songs, but mostly about the graphic novel that was in the works. Artists often make big promises that rarely live up to the expectations. But I think the graphic novel lives up to your tease. Do you think that it will help people finally understand Life House?

No. [laughing] But what the graphic novel does do, which I love, is it makes sense of the two versions of the script that I wrote and makes them into a cohesive whole. It adds some mischief, some humor, some new ideas. But no, it doesn’t, because the idea of Life House being something that brings us into the modern world is kind of nonsensical, really, because there was nothing wireless back then. It was all wire and tubes. So it’s very much stuck in its time.

The songs have been embraced universally over the years, but they were written for a very specific purpose. They’ve stood the test of time, divorced from the Life House project and the Life House story, because the level of writing is very, very high. Does it make sense to you that a song like “Going Mobile,” which is so specific to the Life House project, has been embraced so universally?

Well, you would hope that, wouldn’t you? I grew up in the era of standards. “I’m Gonna Wash That Man Right Out of My Hair” was a song that became universal about breakups and about women finding a dud man and deciding to get rid of him. It was written back in the ’40s, but the song lasted as a standard. So I’m very, very used to that. I grew up very used to the idea that songs [were] multi-purpose. Besides, about half the songs that I wrote for what was then the Life House project, I had no idea where they would fit, or if they would fit, because the project never really started.

I imagined that, once it had got started, there would be a lot of writing which would be specific to how the script unfolded. I imagined that Kit [Lambert] and I would work on it, and he would do with my story what he did with Tommy, when I’d had a story called “Amazing Journey” about a young man, who wasn’t deaf, dumb, or blind, but just a young man who went on a journey. He became deaf, dumb, and blind in a subsequent version of it. And then Kit and I brought in a lot of new ideas, like having an overture repeating, and having a prayer at the end, and switching at the last minute from the fact that he was a good guitar player to a pinball champion. All of those things I expected to happen with Life House, and of course, they didn’t, because Kit was somewhere else. He was out of it on drugs. He was away from London. He was working with Patti LaBelle in New York.

The Who

Let’s talk about exploring electronic music back in 1970. You were working with synthesizers when it was difficult to even coax a melody out of them. And yet, there are some very sophisticated electronic countermelodies on Who’s Next, and also backing tracks that the band eventually played to. Obviously, George Harrison and [Abbey Road engineer] Chris Thomas had used them on “Here Comes the Sun,” but I’m thinking of “Going Mobile” or “Bargain,” where you were one of the first people to crack the code in being able to use synthesizers in a melodic sense. Do you have a memory of working on the demos in your home studio and feeling you’d hit on something truly special and different?

Yeah, I do, and it was very, very exciting. In fact, you’re absolutely right. “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” was another song that was out, which had a Moog thing on it. And so I was listening to that stuff, and when I got my first little EMS box, one of the first things I thought was, “I can play flutes, I can play clarinets, I can play trumpets!” They were funny little noises, but I discovered that these machines allowed me to experiment with melody. I also had a Lowrey organ. I was always surprised that people in rock loved Hammonds so much, because they all made exactly the same sound, while the Lowrey made all these little thin trumpet sounds and little thin violin sounds. “Baba O’Riley” came from the marimba sound that was built into the Lowrey Berkshire that I owned at the time. So I was excited to have these tools, and I think that excitement translated into some pretty interesting stuff. I was on a real high.

I want to talk about the demos. It’s very unusual to get 11 discs and have them be as great as these are. And they even expand on your Life House set from 20 years ago. These are really sophisticated demos, because you’d become an incredible engineer and arranger. But they also tell the story of a lost album, an unrealized project.

Somebody wrote recently something which feels true, which is that Life House, as it exists, is an unfinished project, both as an experiment between artist and audience, but also as a story and an integrated series of songs that help to demonstrate and illustrate that story. It’s basically just conceptual art; coming up with an idea, putting it on paper, and then it not happening. And for me, I’m perfectly happy with that idea. But the fact is that there is no set of songs that tell the story. And when I did the album Lifehouse Chronicles, and the performance at Sadler’s Wells [in London in 2000], I gathered together everything that even in a very, very loose way might have been considered to be associated with Life House. And even then, all it really did was capture the atmosphere of it. Just the intent of it. The feeling of it. The poetry of it. Because it’s a very poetic idea, and that has never really properly come across. It was just ideas that were unfinished.

And the recordings were strewn all over the place. There were songs on Who’s Next, but a bunch were on Odds & Sods and other things that trickled out over the years. Do you look back on Life House and think it’s “the one that got away”? Or are you able to reconcile things now because you were able to make one of the truly great albums of the era, out of all the chaos? Because Glyn Johns writes in his book that, even as late as when you brought him on as producer, you gave him not just the demos, but the script for Life House. So you hadn’t given up on it quite yet.

No, definitely. I was still hoping for a double album. It was a tough time. But it was also a very important lesson for me. I’d given up on the idea of working with Kit, which was a very big thing. I still had the band, and the band was still behind me. When Glyn took over, I was hoping that Glyn would make a double album. That was all. That’s why I gave him the script. And I sat down with him before, and he said, “I really don’t understand this at all.” And I just remember saying to him, “Listen. I hope you don’t feel I’m insulting you, but you really don’t fucking need to. This is my project. Just do what you do.” I didn’t think that we would get to the end of the project and he would decide that the double album was going to be a single album and leave off “Pure and Easy.” I remember thinking that was like leaving fucking “Amazing Journey” off Tommy! It’s the song that sets the scene; that gives the other songs a backbone.

And “Pure and Easy” is absolutely on par with “Baba O’Riley” and “Behind Blue Eyes” and “Bargain” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

Well, it’s certainly on par with “Song Is Over.” Glyn chose “Song Is Over” instead because it was a good closer to the album. He wasn’t thinking about Life House, he was thinking about a bunch of songs, and he made his decisions based on that. But I decided to trust his instincts and his intuition, because by the time we got to the end of the recording, it was clear that Kit was gone for me, and that there was no way I was going to rescue the movie side of the project. And also, the idea that I might be able to do anything technological with the band had drifted into space. But remember, what we had invented was the use of backing tapes. And they fucking worked! That gave us this extra harmonic and musical implementation, because we were just a three-piece band. We didn’t even have a keyboard player. So it enriched our sound. And they worked so well partly because of Keith Moon. He didn’t need a click. He was the click!

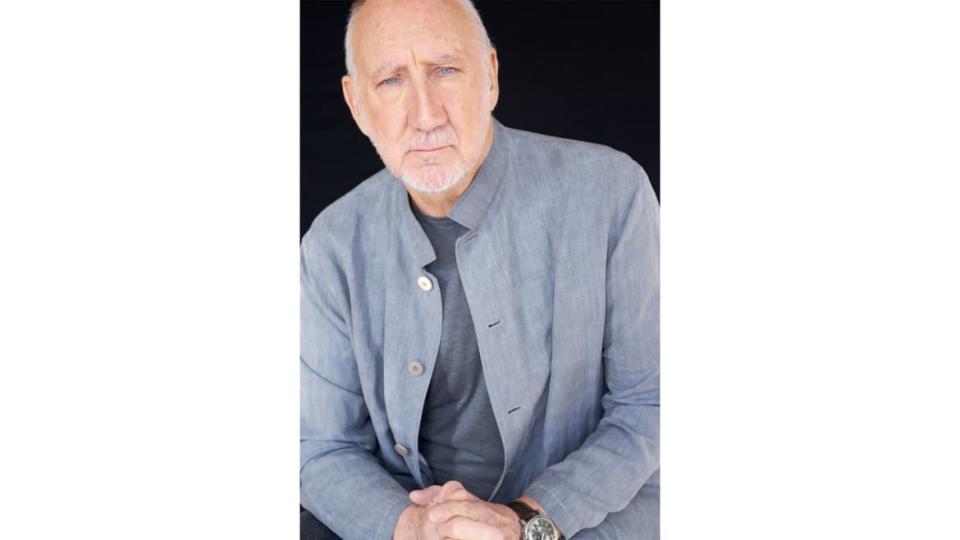

Pete Townshend

At the end of “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” during the San Francisco show included in the box set, you say something like, “Could be rock ’n’ roll, maybe not.” You’d just played a whole bunch of then-new material, the Who’s Next material, to an American audience, and it’s a great performance. I’m sure you don’t remember saying that, but do you remember thinking that the songs or concept maybe weren’t rock ’n’ roll?

I think I’d switched. The Isle of Wight in 1970 was pivotal, because Bob Dylan came over to do the festival. You’d had Woodstock, you’d had Monterey, but we’d had no big festivals in the UK. So it was Dylan, The Who, and the Moody Blues. Dylan’s trip was socio-political folk, still; whatever you wanted to call it. That’s what he did there. Moody Blues were into angels and visions, mysticism, poetic stories about spirituality. And The Who were performing Tommy.

After the show, after the crowd was gone, what was left behind was this incredible expanse of garbage. I mean, it was just spectacular. The festival was only one fucking day. Just unbelievable. And I got our road crew to clean it up. Because I was so ashamed of what had actually happened. And I suddenly thought, because I was working towards Life House, and about the importance of the audience, about trying to raise the audience up, to inspire them, to give them uplift, to make them connect to the realities of how art and politics, and art and society, could be improved, and also, if you like, all under the umbrella of Sufi-spiritualism. Spirituality, not -ism. And here was this example of how little they fucking cared about it. What then happened was I modified my position, and I became more interested in the technology that underlay what electronic music was promising.

Stephen Stills on His ‘Enduring’ Friendship With Neil Young and Butting Heads With Crosby

I remember having lunch with you in 2000, after The Lifehouse Chronicles and the Sadler’s Wells shows, and saying that, in that moment at least, the technology had caught up to your ideas. The Who, at that time, were really on fire. And I said to you that Life House felt like a piece that you could then do and have it be understood. Now, 50-some-odd years on from the germ of the Life House idea, not only has the technology caught up, but the culture has caught up. Plus, there’s an autocratic explosion going on around the world that I’ve always seen as part of the Life House story. Did it ever feel to you, putting together the box set, writing your liner notes, reading the liner notes that other people had written, and the graphic novel, that maybe now is the time to revisit it as a full piece?

No. I don’t think so. I think the possibility now is that the graphic novel might lead to a movie, which will be good, it would be fun. But I think the idea of building an argument, a debate about how people in power wish to use the arts and popular music is a fucking touchy subject, rooted in the fact that musicians, across the board, are like the rest of the populous: polarized into two groups, left and right. There seems to be very little middle.

Plus, in the intervening 20-odd years, we have seen that technology, which we all want to be great, can also be awful. I think that’s the thing that, when I was digging back into Life House, and thinking back to our conversations—and what I know about it, what I’ve read about it, what I’ve imagined about it—is that this good-and-evil part of the technology aspect dovetails into the story very neatly.

I understand you, but I do think also that we need to accept that what’s actually happened with technology, with respect to virtual reality, to communication, is that it’s dividing people into chunks: influencers and followers. And influencers can be musicians. Taylor Swift has her Swifties, for instance. “Teeny boppers” was what Ringo called the Beatles fans. So it’s nothing new. But I think that while we have the technology now to do some of the stuff that Life House is about, what we don’t have is the revolution. We are subjugated. We are suborned. We are all in front of our laptops, with music on our phone. We cling onto our iPhones, and we wonder how we could live without them.

So I think, yes, the technology is nearly there, but what has arrived has already been manipulated and corrupted by money people. All of these billionaire leaders of New Tech are so rich that they could save the world if they wanted to. I don’t know why they don’t, but they choose not to.

So I think what we’re looking at is the fact that there are these entities that get in the way all the time of the people and what the audience wants. I look at people on YouTube or Instagram or TikTok or Reddit, whatever, talking about what they do, and I don’t hear the truth anymore. I hear what they think is cool to do or to say, and sometimes they’re just trying to make money, but I think in a sense of machinery, somehow, we’ve become polarized not just into right and left politically, but also into groups and subgroups of people who only really communicate with each other, honestly, when they’re angry.

So what’s next for Life House and The Who and you as a solo artist?

I don’t know what’s next for Life House, except that a number of film companies and TV companies have seen the graphic novel. And that’s exciting, because they’re all now starting to get it. [laughing] I do feel that the art installation aspect of it is still potentially possible to imagine might take place. The new piece that I’ve been working on for a long time, Age of Anxiety, has an installation conversation aspect to it. So I probably will finish that, and if there are any AI software-based wonderments that come out of the new wave of technology and data manipulation, I’ll probably use them for that project. So, it’s still bubbling.

With respect to The Who, Roger’s got a bad knee which will probably need surgery, and so any decisions now about what we’ll do next, I don’t know. But he’s singing great. He’s still on the right side and I’m on the left side, both in politics and on spiritual matters. And pretty much just life in general. [laughing] But he’s a good guy and he’s working hard and we’re thinking we might try and pick up some of the territories that we’d missed with the orchestral show, but, you know, I’m 78. So I think we shall see what happens. I have to be careful what I say, because I don’t want to make this all about Roger’s fear of what is new, but I think he is afraid of what is new. [laughing] The way he expresses it is, “Pete, you’ve written so many fucking great songs.” He said, for example, “If we were to use your solo catalogue as part of The Who catalogue, we’d have the best fucking choice of stuff.” And already, we don’t have enough time in two and a half hours to play them. He does “Let My Love Open the Door” and he does “Blue, Red and Grey,” I think, in his solo shows. So, something might happen. But I don’t know.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News