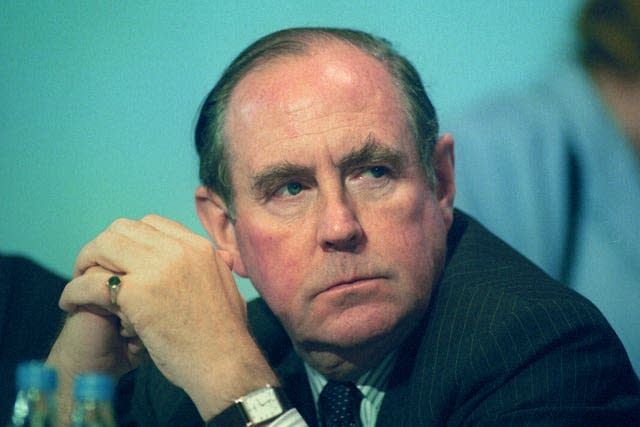

Peter Brooke: Former Northern Ireland secretary served two prime ministers

Peter Brooke, who has died aged 89, was the epitome of the affable English gentleman and served with distinction as Northern Ireland secretary and national heritage secretary.

In 1992, the man who was also chairman of the Conservative Party, came close to being elected speaker of the House of Commons.

Tributes have been paid to Mr Brooke, who later became Lord Brooke of Sutton Mandeville, by former prime minister Sir John Major and Northern Ireland Secretary Chris Heaton-Harris.

He left the Northern Ireland Office before Mr Major’s peace initiative in 1993, but succeeded in his term of office there where many before him had failed, in at least bringing the region’s politicians together around a negotiating table.

His patience was Job-like – a quality that remains much in demand in Northern Ireland – so everyone in Government and beyond was astonished by his blunder in 1992 when he allowed himself to be talked into singing a song on a Dublin chat show, hours after an IRA attack had killed eight building workers in Co Tyrone.

But his offer to resign was rejected as MPs of all parties expressed support for him. The lapse on TV was inexplicable and entirely out of character with the man.

Mr Brooke was dropped from the cabinet after the 1992 general election, almost certainly because the prime minister assumed he was to be elected speaker, but he was pipped at the post and was about to resume a career on the backbenches.

However, David Mellor, the first national heritage secretary, was compelled to resign after his fling with an out-of-work actress and the prime minister was able to restore Mr Brooke to the cabinet without disturbing any other ministerial post.

Mr Brooke’s clipped tones, conservative style of dress and reputation as a classics man – he used to quote Latin and Greek in Camden Borough Council – gave the impression he was something of a buffoon.

But that was far from the case. He was an astute negotiator and was, despite his hesitant mannerisms, firm and decisive when needed.

Peter Leonard Brooke was born in Hampstead, London, on March 3 1934. His father Henry (later Baron) Brooke was a former home secretary.

He was educated at Marlborough, Balliol, Oxford University (where he was president of the Union) and Harvard Business School.

His passion for cricket led to one commentator describing him as “a decent bat on a sticky wicket”, an apt compliment to a man who faced any political – or sporting – problem with equanimity.

Mr Brooke was elected vice-president of the National Union of Students in 1955. He later worked as Swiss correspondent of the Financial Times, a management consultant and as a director of a girls’ school in Switzerland, before joining Camden Borough Council in 1968.

He fought various seats, including Bedwellty against Neil Kinnock, before his election as MP for City of London and Westminster South in 1977.

Always a Thatcher loyalist if not a Thatcherite himself, he was outraged at the refusal of Oxford University to deny her an honorary degree, commenting: “No cause can be considered lost until the University of Oxford has espoused it.”

He was appointed a whip in 1979 and became a junior education minister in 1983, with special responsibility for further and higher education.

In 1985 he became a Treasury minister of state, and was appointed paymaster general two years later.

In November 1987, he succeeded Norman Tebbit as party chairman, although his role was that of a caretaker and he was replaced by Chris Patten who masterminded the Tories’ record-breaking fourth successive election victory in 1992.

Mr Brooke served as Northern Ireland secretary from 1989 to 1992. It was a critical period for Dublin and London, and with his appealing manner and seemingly infinite patience he was more than once able to bring the parties round the conference table.

In a speech in November 1990 he said Britain had “no selfish strategic or economic interest” in Northern Ireland, and would accept unification if the people wished it, a statement seen as a key step in the early peace process.

His impeccable handling of all the parties made him as popular – or acceptable – to those involved as any of his predecessors in what had become a thankless post.

However, his reluctant singing of My Darling Clementine on RTE’s The Late Late Show in January 1992, in the immediate wake of the Co Tyrone massacre, seriously damaged relations with the unionist parties.

In his statement to the Commons the following Monday, Mr Brooke told MPs although his actions were “innocent in intent” they were “patently an error”.

He announced, after apologising unreservedly for his appearance on the show, that he had placed his resignation at the prime minister’s disposal. However, Mr Major voiced full confidence in Mr Brooke after refusing his resignation.

After the election, many of the signs pointed to the choice of Mr Brooke as the new Commons speaker, but Betty Boothroyd beat him to the chair.

To his own – and everyone’s – surprise, Mr Brooke returned to the cabinet after Mr Mellor’s extra-parliamentary conduct forced him out of office.

The prime minister, who always wanted to bring Mr Brooke back into the fold after the disappointment over the speakership, was glad to restore him to the cabinet.

Mr Brooke was firm in this job too, and threatened tough action against the press after the publication of photographs of Diana, Princess of Wales in a private gym.

He said this affair increased the likelihood of a law on privacy. At one stage he called for a press ombudsman to police newspapers’ adherence to a voluntary privacy code.

Mr Brooke remained a bitter opponent of those seeking to beam pornography on to Britain’s TV screens.

He finally left the Government in the prime minister’s reshuffle in the summer of 1994, and in 2001 he stepped down from the Commons and was given a life peerage.

Mr Brooke, known as P to friends and family, married Joan Margaret Smith in 1964. She died in 1985 following complications after a routine surgical procedure.

In 1991, he married Lindsay Allinson, a former constituency agent he met through the Conservative Party.

He had four sons from his first marriage, one of whom died before him.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News