Poorer women in UK have sixth-highest cancer death rates in Europe, WHO finds

Poorer women in Britain have some of the highest death rates from cancer in Europe, an in-depth new World Health Organization study has found.

They are much more likely to die from the disease compared with better-off women in the UK and women in poverty in many other European countries.

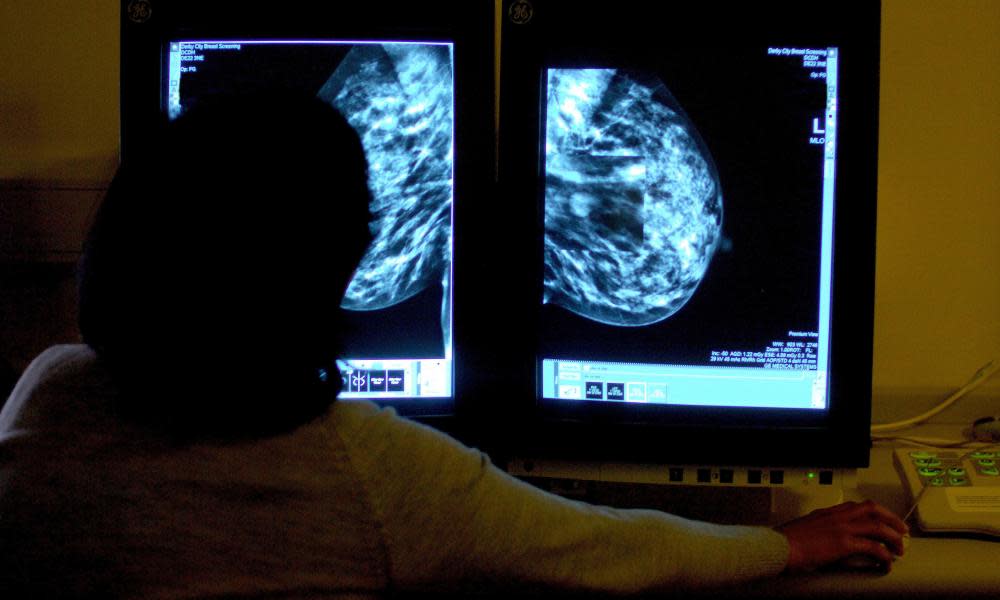

Women in the UK from deprived backgrounds are particularly at risk of dying from cancer of the lungs, liver, bladder and oesophagus (foodpipe), according to the research by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the WHO’s specialist cancer body.

IARC experts led by Dr Salvatore Vaccarella analysed data from 17 European countries, looking for socioeconomic inequalities in mortality rates for 17 different types of cancer between 1990 and 2015.

Out of the 17 countries studied, Britain had the sixth-worst record for the number of poor women dying of cancer. It had the worst record for oesophageal cancer, fourth worst for lung and liver cancer and seventh worst for breast and kidney cancer.

However, the UK has a better record on poor men dying of cancer compared with their counterparts in many of the other 16 countries. It ranked fifth overall, second for cancer of the larynx and pharynx, and third for lung, stomach and colon cancer.

That stark gender divide is most likely because women in the UK began smoking in large numbers some years after men did so, the researchers believe. They pointed to the fact that while cases of lung cancer have fallen among men overall in Britain, they have remained stable or increased among women, and gone up among women from deprived backgrounds.

The research team, which included experts from Imperial College and University College London, used educational attainment as an indicator of deprivation.

“Among men, the UK shows an intermediate level of educational inequalities in all cancers combined, among the European countries included.

“However, among women, the UK shows among the highest educational inequalities in cancer, behind Denmark, the Czech Republic, Poland and Norway,” said Vaccarella.

The study, which is published on Monday in the Lancet Regional Health, Europe, based its conclusions on data collected for adults aged 40 to 79 in 17 countries, including England and Wales. For publication purposes, England and Wales were grouped together.

Far more poor than well-off people die of cancer across Europe as a whole, it found.

“Everywhere, lower-educated individuals systematically suffer from higher mortality rates for nearly all cancer types, relative to their more highly educated counterparts, with a social gradient of increasing risk of death with diminishing education level,” the study concluded.

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) said that women’s health was a key priority and that it is taking action to improve cancer diagnosis and outcomes.

“We are committed to improving the health of the nation and we have put women’s health at the top of the agenda by publishing a women’s health strategy and appointing the first-ever women’s health ambassador for England,” a DHSC spokesperson said.

“We are working at pace to improve outcomes for cancer patients across England, including by improving referral rates. During August, 92% of people started cancer treatment within a month of referral.

“We have also opened more than 90 community diagnostics centres so far, which have delivered over 2m addition scans, tests and checks.”

Related: There is a hidden epidemic of missed cancer cases – here’s how we save lives now | Devi Sridhar

Midnight Meanwhile, the new Tory chair of the Commons health and social care committee has urged the government to clarify whether it intends to bring forward new plans to address the cancer treatment backlog in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Steve Brine, an ex-health minister, told the Press Association that he doubted the government still intends to bring forward a promised new 10-year cancer strategy to improve early diagnosis, treatment and survival.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News