President Javier Milei’s Radical Plan to Transform Argentina

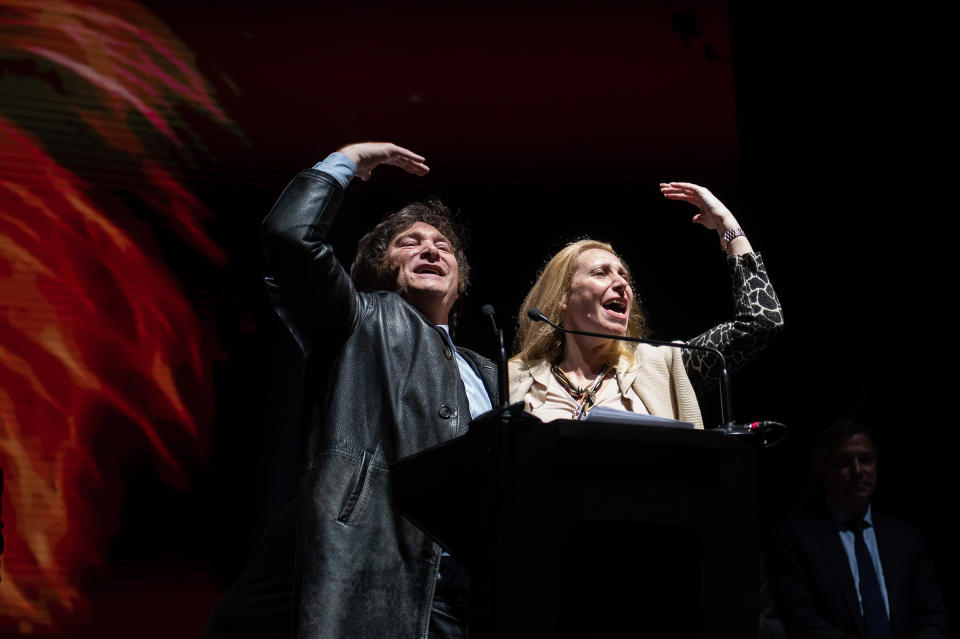

The President in the Casa Rosada on April 25. Credit - Irina Werning for TIME

President Javier Milei hates his new office. The Casa Rosada, with its historic blue chair and ornate paneled walls, feels tainted by his predecessors, who he believes drove Argentina into ruin. But there is one detail Milei loves. Engraved into a fireplace mantle is a bronze lion, the animal he adopted as a symbol during his dizzying rise to power. Showing me around the vast second-floor space, Milei gestures to a blown-up photo of the lion, propped on his desk as a totem of his destiny. “He was waiting for me here,” he says.

Milei may be the world’s most eccentric head of state. Not long ago, he was a libertarian economist and TV pundit known as El Loco—the madman—for his profane outbursts. The oddities of his campaign often overshadowed the stark austerity program he promoted to pull the country out of its economic crisis. Milei, who has bragged about being a tantric sex guru, brandished a chainsaw at rallies to symbolize his plans to slash government spending, dressed up as a superhero who sang about fiscal policy, and told voters that his five cloned English mastiffs, which he reportedly consults in telepathic conversations, are his “best strategists.” He pledged to eliminate the nation’s central bank, derided climate change as a socialist conspiracy, and assailed Pope Francis, the first Argentine Pontiff, as a “leftist son of a bitch.” Last November, he won in a landslide.

The unlikely ascendance of a self-described “anarcho-capitalist” reflects the strength of a right-wing populist movement that has won elections around the world in recent years. Like his counterparts from Italy to Hungary, Brazil to Peru, the U.S. to India, Milei vowed to dismantle a corruption-riddled state ruled by shadowy elites. “Let it all blow up, let the economy blow up, and take this entire garbage political caste down with it,” he said during the campaign. But none of his counterparts is quite like Milei, with his volcanic temper, mad scientist’s bearing—he claims not to comb his wild mop of hair because the “invisible hand of the market” does it for him—and messianic streak. And none of them leads a nation like Argentina, a resource-rich regional power plagued by decades of political mismanagement and economic instability, which has now become a test case for the governing theories of a radical ideologue. “Crossing from the laboratory into the real world is marvelous,” he says with a broad grin. “It’s fantastic!”

Since taking office, Milei, 53, has frozen public-works projects, devalued the peso by more than 50%, and announced plans to lay off more than 70,000 government workers. So far, he sees signs that his economic “shock therapy” is working. Inflation has slowed for four months in a row. The International Monetary Fund has hailed Argentina’s “impressive” progress. Two days before we sat down on April 25 for an hour-long interview, he had given an address to the nation celebrating the “economic miracle” of the country’s first quarterly budget surplus since 2008. Milei thinks he is pioneering an approach that will become a global blueprint. “Argentina will become a model for how to transform a country into a prosperous nation,” he tells me. “I have no doubt.”

Others do. While Milei vowed the “political caste” would bear the brunt, his austerity measures have pummeled ordinary Argentines. The annual inflation rate is still nearly 300%, among the highest in the world. Many Argentines have been forced to carry bags of cash for even small transactions; some stores have given up on price stickers entirely. Milei’s moves—cutting federal aid, transport and energy subsidies, and getting rid of price controls—have caused living costs to spike. More than 55% of Argentines are mired in poverty, up from 45% in December. Milei may be running out of time before his popular support crumbles. “Everybody knew the cost would be huge,” says Argentina’s Foreign Minister Diana Mondino, a close adviser. “What we’re experiencing, nobody likes it. But there’s no other way.”

Argentina’s economy has been bad enough for long enough that polls show a majority of the nation’s 46 million people remain willing to give Milei a chance. Yet it’s not clear the iconoclastic new President is interested in forging the political alliances required to push his sweeping structural reforms through Argentina’s legislature. There are also signs that Milei has misread the scope of his mandate. He won by presenting himself as an antidote to political and economic mismanagement. But it’s clear he also sees himself as part of a broader cultural battle. He has embarked on an international speaking tour, casting himself as a global crusader against socialism, attacking everything from gender-equity laws to climate activists. And in a nation still haunted by the legacy of its brutal military dictatorship of the 1970s and ’80s, Milei’s broadsides against the press and threats against political “traitors” can take on an authoritarian cast. “Much of the support for Milei was for his economic program, not his libertarian vision or anti-woke agenda,” says Benjamin Gedan, director of the Wilson Center’s Latin America Program. “But his view is, ‘You wanted me, and you got me. And I’ll plow ahead.’”

To meet with Milei, you have to go through the person he calls El Jefe, the boss: his sister. On the day of our interview, Karina Milei, sporting silver sequined flip-flops, guarded the door to the President’s office before allowing me in. Karina, 52, is a former tarot reader who until a few years ago was selling cakes on Instagram. Now she controls which journalists her brother speaks with, which photos of him are released, and, reportedly, what Cabinet ministers are hired and fired. (She declined to be interviewed for this article.) One of Milei’s first acts as President was to change a decree barring relatives from Cabinet positions in order to appoint her General Secretary of the Presidency.

Milei’s tight relationship with his sister is an exception. He is said to have few close friends, and is recently single after breaking off a relationship with a glamorous TV actress. Instead, he moved into the presidential residence at Los Olivos with the 200-lb. cloned dogs he calls his “little four-legged children,” each of them named after a famous economist.

Raised in a Buenos Aires suburb, Milei had a troubled childhood. He has said he was physically abused by his father, and declared in TV interviews that he regards his parents as “dead to me.” While he played goalkeeper in a soccer club and sang in a Rolling Stones cover band, classmates mainly remembered him for the furious outbursts that first earned him his nickname.

Milei became interested in economic theory during Argentina’s bout with hyperinflation in the 1980s. He spent the next 20 years as an economics professor, publishing dozens of academic papers and serving as a financial analyst for think tanks, banks, and private companies. In 2015, he began to appear on TV as a pundit, becoming notorious for expletive-ridden tirades against the “political caste.” He emerged as a national figure during the COVID-19 pandemic, going viral on TikTok for his rants against government lockdowns. In 2021, he decided to jump into politics. Karina managed his successful campaign for a seat in the lower house of the legislature, which included an ad that showed him destroying a model of the Central Bank with Thor’s hammer.

Later that year, the Milei siblings created La Libertad Avanza, a new political coalition, to allow him to run for the presidency. At the time, people close to him said in interviews that Milei, who was rumored to hire mediums to communicate with his deceased pet and dead philosophers, believed that God had told him to run for the presidency. “Milei’s driving force is that he truly believes he’s on a divine mission,” says his biographer Juan Luis González. At rallies, fans wore hats with the words “The strengths of the heavens,” a reference to a favorite Bible verse. “I didn’t come here to lead lambs, but to awaken lions,” a leather-clad Milei roared at his events.

He also drew inspiration from outside the country. He pledged to “Make Argentina Great Again,” and his campaign rallies featured posters of Donald Trump and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, along with the Gadsden flags once ubiquitous at Tea Party rallies. Milei channeled widespread anger at Peronism, the left-leaning political movement that has dominated Argentine politics since the 1940s, which championed social justice and workers’ rights but produced an economy that has defaulted on its sovereign debt nine times and owes a staggering $44 billion to the IMF. “He capitalized on the crisis in the old political order,” says Argentine political consultant Sergio Berensztein.

“Viva la libertad, carajo!” became Milei’s famous rallying cry: “Long live freedom, damn it!” Milei has an absolutist’s faith in free markets: he favors loosening gun restrictions to “maximize the cost of robbery,” and has said he would support the sale of human organs. “At first, I told him he would have to take it down a couple of gears,” says Luis Caputo, his Economy Minister. “But it was amazing how the people responded. After a few months, I told him, ‘Never mind—actually, take it up even further!’”

As a running mate, Milei chose Victoria Villarruel, a conservative from a military family involved in Argentina’s “Dirty War” in the 1970s and ’80s. During that period, the ruling junta forcibly disappeared, imprisoned, tortured, or killed tens of thousands of suspected dissidents—a dark chapter in the nation’s history that both Villarruel and Milei have downplayed. Milei vowed he would not bow to “cultural Marxism” and criticized public education as “brainwashing.” The ticket at first drew support from young men who liked his diatribes and social media persona. But faced with the choice between Milei and then Economy Minister Sergio Massa, millions of Argentines were so weary of the economic morass that they were willing to give the outsider a chance. He won with 56% of the vote. “Today one way of doing politics has ended and another begins,” he told supporters. “There is no way back.”

The new way of politics in Argentina is playing out on Milei’s social media feed. The President often stays up until the early morning hours, scrolling on X, formerly Twitter. He’s so prolific on the platform that an Argentine programmer set up a popular website called “How many tweets has our President liked today?” On the day we spoke, he liked or retweeted 336 posts, much of it delirious all-caps praise of himself. “It doesn’t interfere with my job,” says Milei, who tells me he is “addicted to work” and takes breaks only to eat, travel, read economic texts, and play with his dogs in the specially made kennels he had built at the presidential residence.

The administration’s early motto has been “No hay plata”—There is no money. Milei’s austerity measures caused prices to soar, from transportation and food to health care costs. He told Argentines that the effects of his plan would look like the letter V—a steep economic descent before hitting rock bottom, followed by a sharp rebound. In his interview with TIME, Milei declared the worst part was over. “I said that the road would be tough, but that this time it would be worth it,” he tells me, referring to his inauguration speech, in which he asked the public for patience.

But for many, patience is hard to come by. “It’s easy to have patience when you have enough to eat,” said Jorge Alvarez, a 62-year-old street vendor who says the rise in bus fare has made it almost pointless to commute to his jewelry stall in central Buenos Aires. “We all desperately want this to work, but I can’t buy meat anymore,” says Alvarez. “My son can’t go to physical therapy. I can’t travel to see my parents. These are our lives, and there’s a limit to how much we can take at a time.”

The real test, according to both domestic and foreign analysts and officials, will be whether Milei can advance long-term structural reforms while minimizing the social disruptions and backlash that have sunk previous attempts. Milei’s party represents a small minority in both chambers of Argentina’s legislature. Emergency decrees can go only so far; lasting change will require winning elections and making new allies. That, in turn, requires a deft political touch, which is still not Milei’s strong suit. Since taking office, he has branded lawmakers who disagree with him “traitors”; called Colombian President Gustavo Petro a “terrorist murderer,” leading Colombia to expel Argentine diplomats; and blasted Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s wife as “corrupt” at a far-right rally in Madrid, prompting the country to recall its ambassador.

Milei’s first 100 days came and went without any legislative achievements. An omnibus bill that would have given him sweeping executive powers and included measures ranging from the privatization of state entities to penalties for protesters stalled in committee. “If they expected that the President would change the way he is, that’s never going to happen,” Manuel Adorni, his exhausted-looking spokesman, told me in his small office in the Casa Rosada, sipping maté. Earlier in the day, Adorni had spent his press briefing shooting down questions from reporters about his boss’s mental health, spurred by Milei’s repeated reference to having five dogs, even though one is known to have died years ago. (“If the President says there are five dogs, there are five dogs, and that’s the end of it.”)

The media is among Milei’s favorite targets. He has shuttered Argentine state news agency Télam, the only service that covers and reaches into the country’s provinces, accusing it of being a mouthpiece for leftist propaganda. His open hostility to critical journalists, whom he derided in our interview as “extortionists” and “liars,” is amplified by an aggressive network of online supporters. Many who interact with Milei say he sees the world through the lens of right-wing memes. “The place in the world where he is comfortable is social media,” says Lucía Vincent, a political scientist at the National University of San Martín. Milei divides the public into two camps, Vincent adds. The first is “supporters who only see your actions as a crusade for good,” she says, “and anyone beyond that border as an enemy who must be exterminated.”

One day in late April, more than a million Argentines took to the streets in what turned into the largest protests of Milei’s presidency. Tens of thousands crowded into the Plaza de Mayo in central Buenos Aires, lifting books above their heads in opposition to the drastic budget cuts to public universities. The sunny day had the atmosphere of a festival, with vendors selling choripán and ice cream, and young demonstrators dancing to Latin rock.

Among the most common signs hoisted by protesters was a simple plea: “Cuidemos lo que funciona” (Let’s protect what is working). Budget cuts and ongoing inflation had led university officials to declare a financial emergency, warning they would soon run out of money. At the renowned University of Buenos Aires, hallways were dark; classrooms went without air-conditioning in an effort to save on energy bills. “We have never experienced this situation before in the last 40 years of democracy,” says the university’s chancellor, Ricardo Gelpi, calling the cuts an “extremely grave situation compromising the future of hundreds of thousands of Argentines.”

It was clear that Milei had touched a third rail of Argentine society, which prides itself on its public higher education. But the President lashed back. In posts on X, he accused the universities of “indoctrination” and tweeted a cartoon of a lion drinking a mug of “leftist tears.” When I raise the protests during our interview, he immediately flashes the fury that first made him famous on television. “Are you then in favor of a group that, because they lost the elections, tries to stage a coup?” Milei asks me, leaning over the table and raising his voice. “They made up a lie, which led society to march,” he tells me, dismissing the student protests as a cynical ploy by left-wing opponents. “Those people complaining are the same ones who sank Argentina.” Then he leans back with a placid smile, as if a switch had been flicked. “Everything we’re accused of is false.”

The realities of the office have prompted Milei to ease off a few of the targets of his ire. Backpedaling from his broadsides against Pope Francis, who is widely beloved in the predominantly Catholic country, Milei visited him in Rome with alfajores cookies. During our interview, Milei seemed to soften several key campaign positions, including plans to replace the peso with the dollar and refuse to do business with China’s “communist assassin” regime—a policy evolution that likely owes to Argentina’s dependence on Chinese investment and trade.

Milei’s antipathy toward Beijing, which invested heavily in Argentina over the past two decades as part of its bid to exert influence in the region, is a break from his predecessors. He withdrew Argentina from a plan to enter the BRICS alliance, which includes Brazil, Russia, India, and China, and instead asked to join NATO as a global partner. Despite their obvious differences, the Biden Administration has scrambled to seize the opportunity to forge ties in a region where China has been ascendant. A parade of high-ranking officials have trekked to Buenos Aires, from Secretary of State Antony Blinken to General Laura Richardson, the U.S. Southern Command chief. In April, the U.S. announced $40 million in foreign military financing. American officials say Milei is surprisingly easy to work with. He is reachable directly on WhatsApp, where he swaps messages freely, exchanging lion emojis with U.S. Ambassador Marc Stanley.

Milei has also tempered his prior criticism of President Joe Biden, whom he once labeled a socialist. “Given my current role, I handle things cautiously,” he says. Yet it’s clear whom he favors in the 2024 elections. In addition to aping Trump’s campaign slogan, Milei has spoken at CPAC and given interviews to right-wing media figures like Tucker Carlson and Ben Shapiro. “President!” he shrieked in a video posted of a February encounter with Trump, enveloping him in an ecstatic hug. “I hope to see you again, and the next time I hope you will be President.” For his part, Trump—as he is wont to do—took credit for Milei’s victory. “He ran as Trump,” the Republican said in December. “Make Argentina Great Again. It was perfect.”

But in important ways, the two men are very different. “Milei is a rigid ideologue, a true believer,” a senior U.S. diplomat told me, “and Trump only believes in himself.” Milei believes he was elected for his promises of a broader cultural revolution, not in spite of them, and he is intent on realizing that mission no matter the political costs. Making the nation “Great Again” means “returning to those libertarian values that made Argentina a leading global power,” he told me. “That is my vision.”

Instead of traveling to meet other heads of state, Milei has been appearing at international conferences to rail against socialism. At Davos, Switzerland, he warned “the West is in danger” and accused its leaders of being “co-opted” by “radical feminism” and “neo-Marxists.” He has met twice with Tesla CEO Elon Musk, whom he sees as a prominent ideological ally. “There’s an economic battle, a political battle, and a cultural battle,” Milei says. “We believe post-Marxism ... could lead the world to ruin.” But while he relishes his rising international profile, Milei knows his success will be determined at home. On April 30, he notched his first legislative win when a curtailed version of his omnibus bill was approved by the lower house of Congress. “We strongly believe this is the only way,” Mondino, the Foreign Minister, says of Milei’s severe austerity program. “When the French Revolution started, lots of people died. It was chaos. But 15 other countries opened up within 60 years.”

Success will require Milei to make new allies, including members of the political “caste” he has spent years railing against, and to maintain public support amid brutal cost-cutting. Unlike perhaps any other leader elected in the wave of right-wing populism that carried Argentina’s anarcho-capitalist leader to power, Milei has shown he will follow through on the radical plans he campaigned on. “The world is watching,” says Caputo, the Economy Minister. “Because if Argentina manages to reverse this, it means that anyone can.”

Write to Vera Bergengruen at vera.bergengruen@time.com.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News