Exclusive: Public Health England will not deliver Covid vaccines on Sundays

Public Health England has decided not to work on Sundays to deliver Covid-19 vaccines to NHS hospitals, according to leaked documents, amid growing questions over the urgency of the UK roll-out.

Guidance issued to NHS Trusts warns that PHE will not deliver vaccines on Sundays or after agreed "cut-off points" every lunchtime, even if supplies are running low.

It comes despite the Boris Johnson's pledge to use "every second" in the coming weeks to put an "invisible shield" around the vulnerable and elderly through mass vaccination.

The standard operating procedures issued to NHS Trusts for ordering vaccine supplies from PHE warn that next-day deliveries should only be expected from Monday to Friday, as long as orders are placed before 11.55am.

Orders placed on the PHE portal on Friday afternoons and Saturday mornings will not arrive until Monday, while orders placed on Saturday afternoons will not be delivered until Tuesday, according to the documents seen by The Telegraph.

"An emergency delivery schedule is not available," the guidance warns. "Orders after cut-off will be processed the next day."

A PHE source insisted on Tuesday night that exceptions would be made – including Sundays – if hospitals were genuinely at risk of running out of vaccine supplies. "You need a cut-off point or the whole system would fall over. And we agreed the six-day week with the NHS," the source added.

An NHS source said trusts expected PHE to move to a seven-day schedule once further vaccine supplies came on stream.

Meanwhile, Mr Johnson suggested on Tuesday night that any delays in the supply of Britain's approved Covid vaccines were being caused by the necessary safety checks.

The regulator – the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) – insisted it was working with AstraZeneca, the pharmaceutical giant that has developed the Oxford University jab, to ensure vaccine batches are approved for use "as quickly as possible".

The Prime Minister hinted at delays, saying: "The rate-limiting factor at the moment is making sure that we can get enough vaccine, where we want it fast enough.

"And one of the problems is that the AstraZeneca vaccine, which has just come on stream, needs to be properly batch tested, properly approved before it can be put into people's arms, and this is just a process that takes time to do. But we will be ratcheting it up over the next days and weeks."

Senior Government sources said on Tuesday night that there was no frustration with the MHRA and that the NHS and drugs companies were on track to deliver two million vaccinations a week. The source said any slow start was due to the need for AstraZeneca to scale up production in the run-up to receiving approval.

The Government is confident it can deliver more than two million jabs a week by February, but not confident enough to go public in case the production cycle hits any unforeseen snags.

New figures released on Tuesday showed 1.3 million people have now had a first dose of a Covid-19 vaccine in the UK. Most have had the jab produced by Pfizer/BioNTech, including about 700,000over the age of 80 – amounting to almost a quarter of the 80-plus population in the UK.

The Oxford/AstraZeneca roll-out began on Monday, and it is available in only six hospitals for the first few days to ensure the process runs smoothly.

Based on current figures, the Government is a long way from delivering the two million doses a week needed for Mr Johnson to fulfil his promise to offer first vaccinations to everyone over 70 as well as the clinically vulnerable – a total of 13.4 million people – by mid-February.

The drugs companies have dismissed suggestions they cannot supply the vaccine quickly enough. Pfizer has about five million doses available in vials and ready for use in the UK, while AstraZeneca has four million in vials, of which 3.5 million still need safety approval from the MHRA before use.

A further 15 million doses are frozen and stored in bulk, waiting to be shipped and then defrosted and put in glass vials in a process known as "fill and finish".

Ministers and officials had suggested that a shortage of vaccines threatened to disrupt the roll-out, but the drugs companies involved in the manufacturing chain are adamant supply is on track.

Suggestions of issues with such mundane items as the acquisition of tens of millions of glass bottles to contain the vaccine doses have been scotched.

Pfizer said its supply was on track, while AstraZeneca said it had also experienced no delays. Oxford Biomedica, the main manufacturer of the "raw" vaccine in the UK for the Oxford/AstraZeneca jab, said it was running at full production, having stepped up its manufacturing in October.

The frozen vaccine is then sent to "fill and finish" plants outsourced by AstraZeneca, including the main hub in the UK at Wockhardt, in Wrexham. That stage of the process takes less than a week, according to AstraZeneca, including a day or two for the large-scale vaccine to thaw before it is put in sterilised vials.

Wockhardt said its production processes were running as planned. A source said: "It isn't experiencing any supply issues with regards to vials. Wockhardt is operating on a 24/7 basis to supply the fill-finish process of the Astra-Zeneca Covid-19 vaccine to the NHS for the UK Government."

Health sources have said that the vaccine was never going to be rolled out at two million jabs a week from the get-go. Sources said launching the biggest mass vaccination programme in history from scratch was always going to be a difficult logistical exercise that would take time. Mr Johnson may not have time.

But there will be anxiety that MHRA checks may hold up an already difficult process. It is unclear how the MHRA was able to approve 500,000 Oxford doses within hours of giving the vaccine emergency approval just after Christmas but that 3.5 million doses – many days later – are still awaiting batch clearance.

An MHRA spokesperson said: "We are working closely with the manufacturer, AstraZeneca, to ensure that batches of the vaccine are released as quickly as possible."

The MHRA added: "Biological medicines, such as vaccines, are very complex in nature and independent testing, as done by the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, is vital to ensure quality and safety.

"NIBSC has scaled up its capacity to ensure that multiple batches can be tested simultaneously, and that this can be done as quickly as possible, without compromising quality and safety."

The MHRA pointed out batches can contain "many thousands of doses" and that "the production of complex biological medicines, such as vaccines, cannot be controlled in the way it can for chemical-based medicines like paracetamol". It meant t"in-depth laboratory testing for quality of the final product is needed".

Around 13.4 million Britons fall into the top four priority categories set out by the joint committee on vaccination and immunisation (JCVI) and vaccinating them all would prevent around 88 per cent of deaths, offering the first real escape route from the pandemic.

The mass programme is far beyond anything attempted by the NHS to date, vastly exceeding the numbers achieved by the winter flu jab.

Around nine million people receive the flu jab each year, and that programme is rolled out over a five-month period between September and January, peaking around October when up to 180,000 injections a day are given.

But that is well below the levels required to hit coronavirus targets of 300,000-400,000 which will be needed.

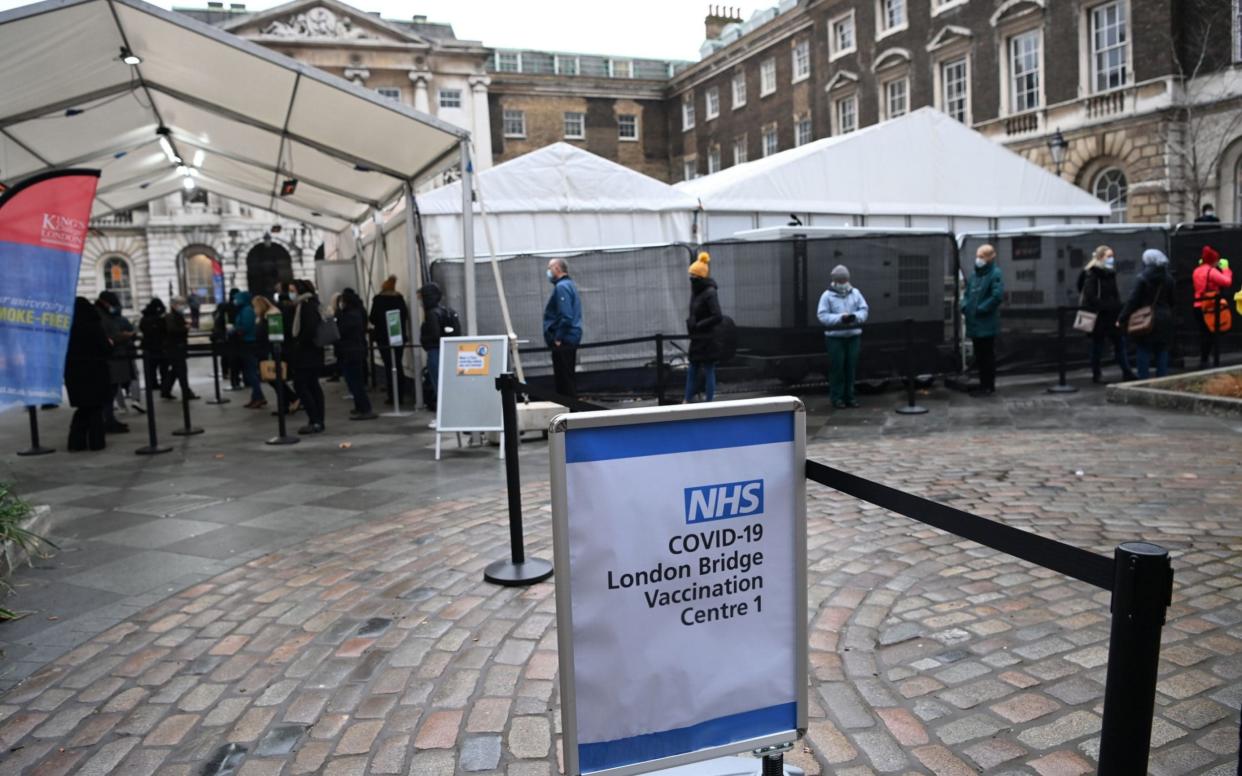

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) said that 730 vaccination sites are already live across Britain and 1,000 will be open by the end of the week. The NHS initially drew up plans for 1,500 vaccination centres to be ready by December 1.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has called on the Government to allow pharmacists to administer the vaccinations, and take pressure off doctors and nurses.

“Community pharmacists already provide flu and travel vaccinations,” said Sandra Gidley, president of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society.

“Through pharmacies, the NHS has a ready-made workforce of skilled vaccinators who should have the opportunity to play their part to speed up delivery of the jab to priority group.

“They could provide easy, local access for patients to the Oxford vaccine and we are working with the Government and the NHS to help make this happen.”

But analysis by Imperial College suggests that it is possible to achieve the goal. They suggest ramping up to 400,000 doses per day, seven days a week for 50 days to meet adequate coverage.

“It’s an ambitious target and needs everything to click every day,” said Professor Nilay Shah, head of the department of chemical engineering, Imperial College London.

“But we should aim for it and give it focused attention from everyone in the system.

“Our analysis indicates that at steady-state it would be possible, with a great deal of coordination of manufacturing, logistics, rapid training of vaccination administration personnel, co-operation of patients, it should be possible to reach daily vaccination levels of 300,000 to 500,000 doses per day.”

Michael Brodie, interim chief executive of PHE, said: “We run a seven-day-a-week service and have fulfilled 100 per cent of orders from the NHS on time and in full – with routine next-day deliveries six days a week as agreed with the NHS and the capability to send orders on Sundays if required. We are working around the clock to distribute millions of doses all over the UK and can deliver as much available vaccine as the NHS needs.”

On Tuesday night the World Health Organisation recommended that two doses of the Pfizer jab are given within 21-28 days.

It comes after the UK decided a second dose could be given as much as 12 weeks after the first dose.

"We deliberated and came out with the following recommendation: two doses of this (Pfizer) vaccine within 21-28 days," Alejandro Cravioto, chairman of the WHO's Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE), told an online news briefing.

The panel said countries should have leeway to spread out shots over six weeks so that more people at higher risk of illness can get them.

"SAGE made a provision for countries in exceptional circumstances of (Pfizer) vaccine supply constraints to delay the administration of the second dose for a few weeks in order to maximise the number of individuals benefiting from a first dose," Mr Cravioto said.

He added: "I think we have to be a bit open to these types of decisions which countries have to make according to their own epidemiological situations."

On Tuesday night Professor Chris Whitty, the UK's chief medical officer, defended the decision to delay the second dose, which he said was endorsed by scientific and medical bodies.

He added: "We've done this based on a number of different scientific lines of decision-making, and that is to allow us to maximise over the first 12 weeks a number of people who can be vaccinated.

"That should provide a high degree, not the complete protection, because everybody should have their second dose at 12 weeks, but that should provide a high degree of protection."

Yahoo News

Yahoo News