Is it really healthy to use tradition as a comfort blanket? | Catherine Bennett

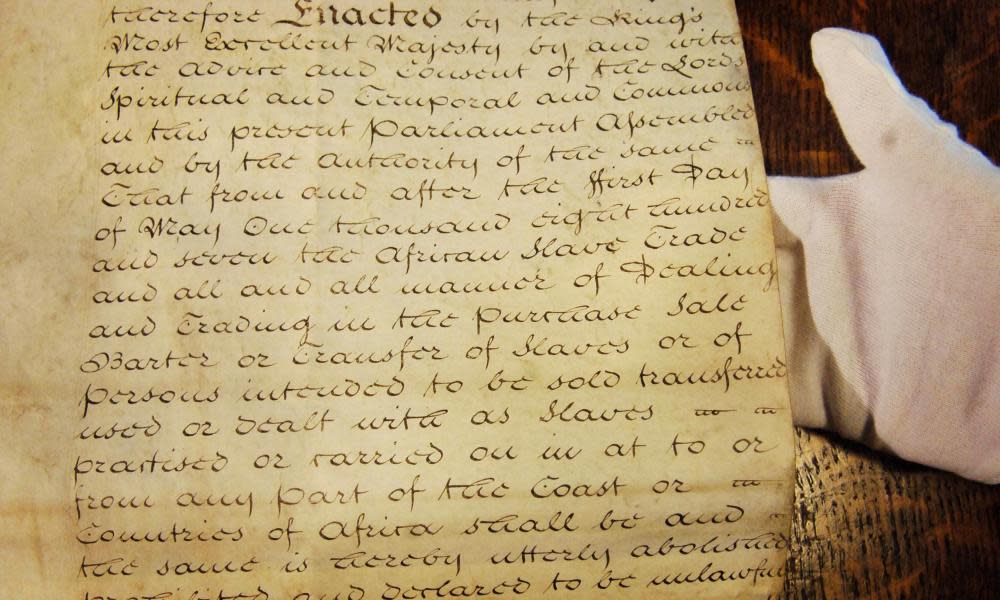

It may yet to be reflected in the crime statistics, but, as of January, Britain’s laws have been, to quote Jacob Rees-Mogg, “in some sense lesser”. That, at least, was his mournful prediction in the Guardian, should parliament choose to give up recording public statutes on vellum – calfskin – and print them on cheaper, archival paper instead.

Woeful indeed, Rees-Mogg warned last year, as the vellum argument raged back and forth, between the pro-vellum Commons and the anti-vellum Lords, would be the consequences if, for an estimated annual saving of £80,000 (excluding a replacement printer), some laws ceased to be written on a material first introduced to Britain in the middle ages.

The practice of printing parliamentary statutes on vellum began rather later, in 1849. Though only a child at that time, Rees-Mogg clearly appreciated the metaphorical significance of choosing tough, long-lasting vellum over flimsy, newfangled paper. “The permanence of vellum,” he argues, “is a statement that the law is important, which indeed it ought to be.” The creators of the Ed Stone are finally, you take it, vindicated.

After a brief reprieve, which came courtesy of the like-minded Matthew Hancock, the minister of state for digital and culture, the end of the vellum tradition has been announced, with consequences for law and order at which we can only guess. Supposing Hancock was not being fanciful, when he argued, while defending vellum in the Commons, that this material uniquely “underlines the point that the law of the land is immutable and that the rule of law is steadfast”, we stand to lose, as a society, more than an obscure, if relatively recent, parliamentary tradition. We are looking at a traditionalist crime wave.

Can paper statutes hope to restrain those of us who only respect laws that have been printed on finest quality calfskin, from the country’s last vellum producer? Hardly, and the risk must be, it follows, all the greater from vellum-addicted homes where parental respect for the law is most strongly linked to the physical aspects of its preservation.

Who would wish to be living near the Rees-Moggs clan, with their five children, in the new era of “lesser” laws “not worth the vellum they were once written on”? Perhaps it is no coincidence that Rees-Mogg, a keen Brexiter revered by the far-right Traditional Britain Group, was among the first to challenge the rule of law following the article 50 judgment in the high court. “There has been a growing problem of judicial activism,” he complained: a foretaste of the paper-induced sociopathy to come?

If, on the other hand, society can be protected from the vellum-deprived criminal mind, by, say, exemplary sentencing, some of its champions may regret that they did not argue – as the only possible reason for printing on calfskin – that this tradition is at least as old as tartan, therefore time-hallowed and unimprovable. Do away with printing on vellum purely because, as its opponents say, it is an unjustifiably costly, nonsensical affectation whose significance, supposing it had any, is bound to be lost on the vast majority of the public, and where do you stop?

Next thing, the modernisers will want to get rid of the snuff, kept in a wooden box with a silver lid, which is still on offer to MPs off to study their iPads in the Commons chamber. Lose parliamentary vellum for practical reasons and you might as well jettison parliamentary ermine, robes, prayers, maces, the preservation of Norman French, shouts of “hats off, strangers”, bowing to the cloth of estate, rituals so numerous and arcane that they require lengthy handbooks for the induction of new members.

It might not stop there. Abandon vellum, for which in an unsentimental market economy there is no justification beyond tradition, and in no time any similarly phony constitutional requisite could be at risk, not excluding the coach rides and fancy-dress outfits that are so critical in distinguishing Prince William, member of the Order of the Garter, from the averagely challenged yah in a jumper and desert boots. Admittedly, it’s possible that the survival of most of the above is dependent on their remaining as hidden as possible.

Whereas the luxury of a royal family is clearly synonymous with a supply of showy routines, including those choreographed in 1948, the ceremonial depicted in the recent BBC2 series, Meet the Lords, only broadcast the inanity of that entire institution. Almost more eye-opening than Black Rod prancing about in his stockings and breeches, the dedicated dresser and hereditary coathooks, the Yeomen of the Guard looking for gunpowder – to say nothing of the traditional gluttony and servility on display – was the obvious conviction, among many of its mediocrities, that their play-acting was impressive.

Yes, their then Speaker, Baroness D’Souza, admitted, some lords were taking the piss, stipend-wise, but we knew that. More revelatory, surely, and no less damaging, was the place’s investment in rituals, including by shamefaced participants who could have declined their honours, to the point of making the Commons’ champions of vellum look au courant.

Alas, now is not the time, to borrow the phrase of the moment, to expect any mystique-depleting modifications. In any case, it’s a measure of the Lords’ self-awareness about impenetrable tribal customs that, during a recent in-house attempt to reform the place, proposed by Jenny Jones, one of the twerps rebuked her for speaking like a normal person. “Would the noble baroness permit me to ask her to address the house and not individuals within it?” said Lord Elton. “We do not say ‘you’, we say ‘noble lords’”.

True, this was just before non-lords had a chance, courtesy of the BBC, to see what happens to the brains of noble lords who have gone native, but, as memories of that horror subside, there is probably every reason, as Brexiters crave symbols of British exceptionalism, for peers to feel complacent about their services to tradition, the national comfort blanket.

Boris Johnson, along with others who should know better, is already agitating for a replacement Britannia. Such a craft, Lord Lexden, the Conservatives’ historian, wrote to the Telegraph (which is campaigning on this account) would fulfil a “deep longing” for Britain to show that it is “confident about our capacity to shape a new national destiny”. Had it not been for Blair, we might have one already. “History and tradition,” Lexden said, “meant nothing to New Labour.”

If there is anything less confident, more inadequate, than a country that needs a new symbolic boat to feel good about its future, it is probably a lawmaker who fears that laws won’t work without special parchment or a legislature whose stature relies as much on regal props as on reason. You don’t have to be a poptastic, Blair-style neophile to lament the quite random objects and conventions that parliament makes time to fetishise, merely an opponent of magical thinking in government.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News