From Rebus to The Responder, it’s time to bury the defective detective

In the 1920s, during the so-called Golden Age of crime writing, a Catholic theologian and literary critic, Ronald Knox, published a list dubbed the “Ten rules of detective fiction”. This was an attempt at trope-busting in a genre that, all too frequently, slipped into hamminess and absurdity. Under Knox’s instruction, writers were restricted to “not more than one secret room” and banned from the use of “twin brothers” altogether. But perhaps the most obvious of Knox’s prohibitions was a simple one: “The detective must not himself commit the crime.”

Yet within the first three minutes of the BBC’s new adaptation of Ian Rankin’s Rebus novels – titled simply, like the ITV/Ken Stott version of the Noughties, Rebus – the protagonist, a detective inspector, is beating the bejesus out of a suspect in custody. The line between the men (and it is usually men) who solve crimes and those that perpetrate them is a thin one. For all of Knox’s proscriptions, he failed to eradicate cliche from the genre. One cliche simply gives way to another, and none has been more pervasive or resilient than the copper dealing with a mountain of personal issues. Is it time, then, to add an 11th commandment to Knox’s list: the detective’s life must not be totally falling apart.

Look, detectives have always had their vices. Hercule Poirot’s was vanity, Nero Wolfe was an agoraphobe, Sherlock Holmes was a junkie. On TV, these personal failings are all the more pronounced: Martin Rohde (The Bridge) is a philanderer, Rust (True Detective) is an alcoholic, Fitz (Cracker) goes in for just about every iniquity on offer. Mother of God, even Line of Duty’s Ted Hastings, the avuncular uncle of TV detectives, went bankrupt and ended up living in a Travelodge. In fact, writers deploy this trope with such frequency that it even has its own name: the defective detective.

The reasoning behind it is simple writer’s logic. The detective is the voice of authority, who must have a spark of either genius or pragmatism that serves the administration of justice. To offset this, and avoid entering banal superhero territory, they must also have a foible or two that makes them relatable, and usually scuppers the simple, and quick, progression of the case. Think about how effective Gregory House would’ve been at triaging his exotic patients if he weren’t addicted to Vicodin. A better doctor perhaps, but, like his inspiration Sherlock Holmes, a less engaging character.

This was all well and good when the crimes were bloodlessly dispatched bodies in libraries, or when the milieu was an Oxford college or the colourfully rendered streets of Victorian London. But, in recent years, the police procedural has become the preeminent form of televisual social realism. The tensions and ills of society – from institutional racism to opioid addiction, knife crime to human trafficking – provide much of the backdrop to notional “detective” shows. This is perhaps why we now call them “crime dramas” rather than “murder mysteries”. These shows seem to proclaim that it’s a f***ed up world – but murder is already a f***ed up crime and these detectives are all totally f***ed up too, and, frankly, that’s too many f***s for one sentence.

Patricia Highsmith, arguably the greatest crime writer of the second half of the 20th century, authored a book on thriller writing, in which she observed that “it is possible to make a hero-psychopath one hundred percent sick and revolting, and still make him fascinating for his very blackness and all-round depravity”. But most of the current spate of TV dicks could hardly be called “fascinating”. The Responder, Bloodlands, Strike, True Detective, Unforgotten, Marcella, and now Rebus. Our detectives are depressed, corrupt, drunk, socially dysfunctional, and violent. They scream and shout, punch and kick (and then maybe get weepy with a token woman, perhaps a therapist or ex-wife), but display little of that redemptive quality: charisma.

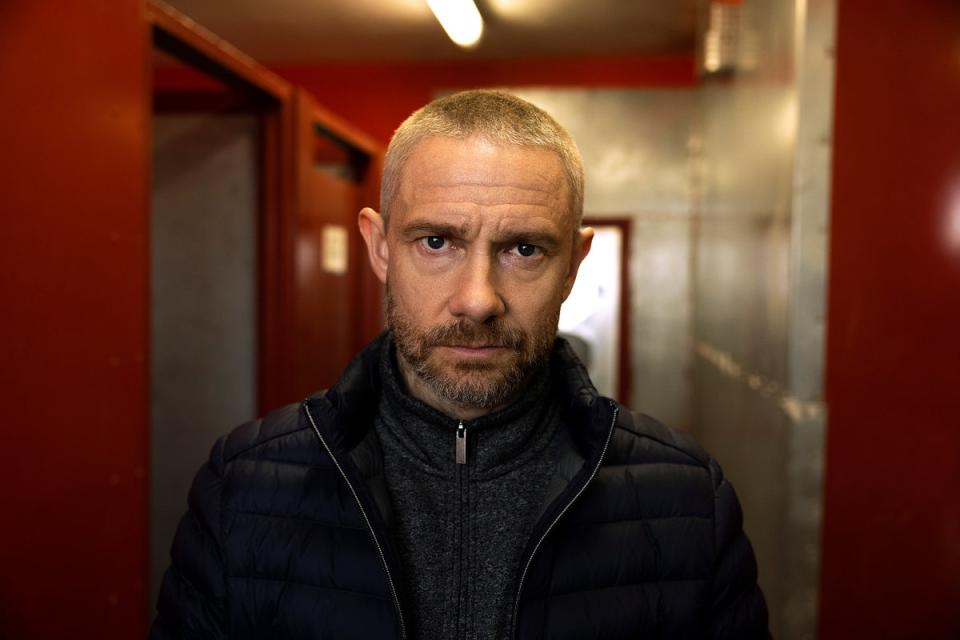

With Inspector Rebus returning to our screens this week for the first time since 2007, we are surely due a reappraisal of whether the heroes of crime dramas need to be so tediously, and predictably, fragile. Happy Valley was a success because of its fusion of Hitchcockian elements and earthy Yorkshire wit. The trauma and PTSD of Catherine, the show’s heroine, was an important motivator for her character, but never allowed to supersede a commitment to entertainment. But watching Martin Freeman cruising around nocturnal Liverpool in The Responder, cursing his lot in life, it’s hard not to wish that some of that Calder Valley charm could make its way into the Scouse gloom.

Rankin – whose Rebus novel series was seen as a progenitor of “Tartan Noir”, a school of hard-boiled Scottish fiction – was a key player in reshaping expectations about the detective novel. But as the opening music of the new Rebus plays (“Truth be told,” a voice warbles, “I’m not the man that I once was”), it’s hard to escape the feeling that far from being a reinvention of a tired, fusty formula, these troubled detectives have become the dead-eyed default. What began as a reaction to the twee eccentricity of Golden Age gumshoes – from Peter Wimsey to Miss Marple – has become just as staid, just as removed from the real spectrum of human experience.

So whether in a shallow grave, under your mother-in-law’s patio, or weighed down and sleeping with the fishes, perhaps it’s time to finally bury the defective detective, once and for all.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News