‘Red alert’ on climate crisis as number of people going hungry around world doubles, UN report says

The number of people going hungry around the world has more than doubled in the past four years, as the world’s leading weather agency sounded a “red alert” on the climate crisis.

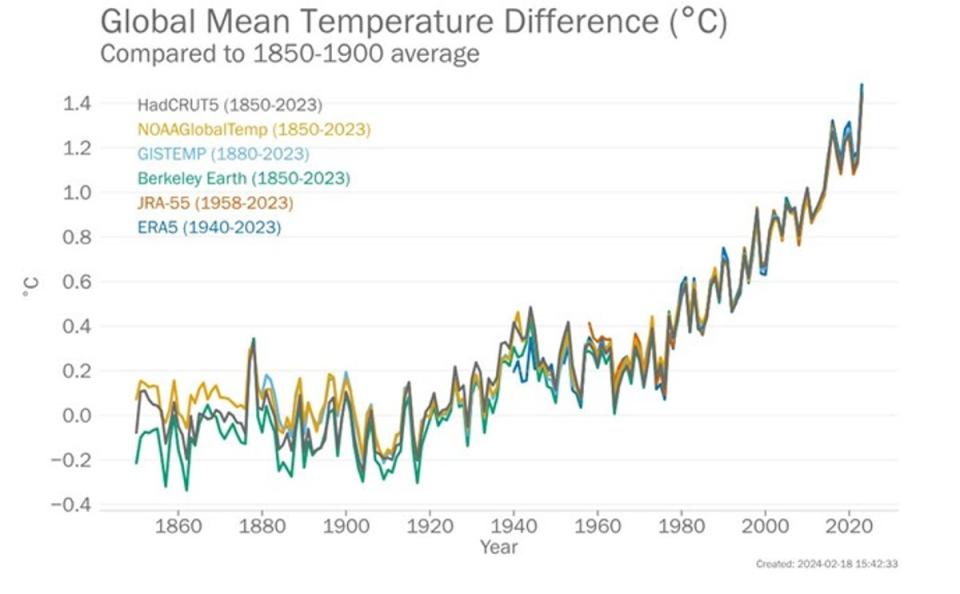

2023 was the hottest year on record, the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) declared on Tuesday, echoing a host of other scientific bodies that have drawn the same conclusion.

The global average temperature was 1.45 degrees Celsius hotter than in pre-industrial times in 2023, drawing perilously close to 1.5C – a critical threshold agreed by world leaders, beyond which lie potentially irreversible impacts.

Scientists have warned that 2024 is shaping up to be another record-breaking year of high temperatures.

“Never have we been so close to the 1.5C lower limit of the Paris Agreement. The WMO community is sounding the red alert to the world,” WMO secretary general Celeste Saulo said.

One of the most concerning findings of the WMO report is the dramatic surge in food insecurity around the world in just a handful of years.

Before the pandemic, 149 million people were classed as “acutely food insecure” – meaning they did not have enough food to meet their daily dietary needs. In just four years, that number has more than doubled to 333 million.

Heatwaves, droughts and floods have played a role in the hunger crisis, the WMO said. The extreme events, many driven at least in part by the climate crisis, have led to widespread crop failures and prompted vast numbers of people to uproot from their homes, with the most vulnerable at the greatest risk.

Prolonged drought in east Africa has pushed millions into food insecurity, with multiple failed harvests and the death of livestock on a large scale. In Zimbabwe, nearly 8 million people, half the population, are severely food-insecure.

“The climate crisis is THE defining challenge that humanity faces and is closely intertwined with the inequality crisis – as witnessed by growing food insecurity and population displacement, and biodiversity loss,” Ms Saulo said.

UN secretary general Antonio Guterres called the report a “distress call” from the planet.

“The state of the global climate report shows a planet on the brink,” he said on Tuesday. “Fossil fuel pollution is sending climate chaos off the charts. Sirens are blaring across all major indicators.

“Some records aren’t just chart-topping, they’re chart-busting. And changes are speeding up.”

The WMO’s 2023 report also found that:

Ocean heat reached a record level in 2023

A third of the world’s ocean cover suffered marine heatwaves daily in 2023 – surpassing the previous record of 23 per cent in 2016

Sea level rise has doubled since the 1990s

Glaciers in western parts of North America and the European Alps went through an “extreme melt season”. North American glaciers lost 9 per cent and Swiss glaciers lost 10 per cent of their volume in just the last two years

Professor Jonathan Bamber, director of the Bristol Glaciology Centre at the University of Bristol, said the speed with which glaciers are melting is “staggering”.

“If that trend continues then we could see much of the Alps devoid of glaciers in a matter of decades,” he said.

The report did contain some good news when it came to renewable energy. In 2023, there was a nearly 50 per cent increase in renewable energy capacity: the highest growth rate in the past 20 years.

The WMO called for an urgent expansion of renewable energy and more finance to help developing countries to transition and adapt to extreme weather.

“The faster we transition to using [renewables], the more money we save the global economy,” said Dr Cameron Hepburn, professor of environmental economics at the University of Oxford.

The money pledged by developed nations for climate action and adaptation measures has nearly doubled so far this decade, the WMO said. However, it still falls far short of what is required, and must increase sixfold to meet the scale of climate challenges.

“Worryingly, the gap between scientific evidence, action, and finance to mitigate and reduce future impacts is not closing, and the climate emergency alarm bells keep on ringing,” said Dr Robert Marchant from the department of environment and geography at the University of York.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News