Reform’s polling surge threatens Tory seats, but has it hit its peak?

The Labour lead in the opinion polls has been 20 percentage points throughout the campaign. But the polls haven’t been entirely static.

Over the past five weeks there has been one key change in polling that has the potential to turn a historic defeat for the Conservatives into an obliteration when the election is called.

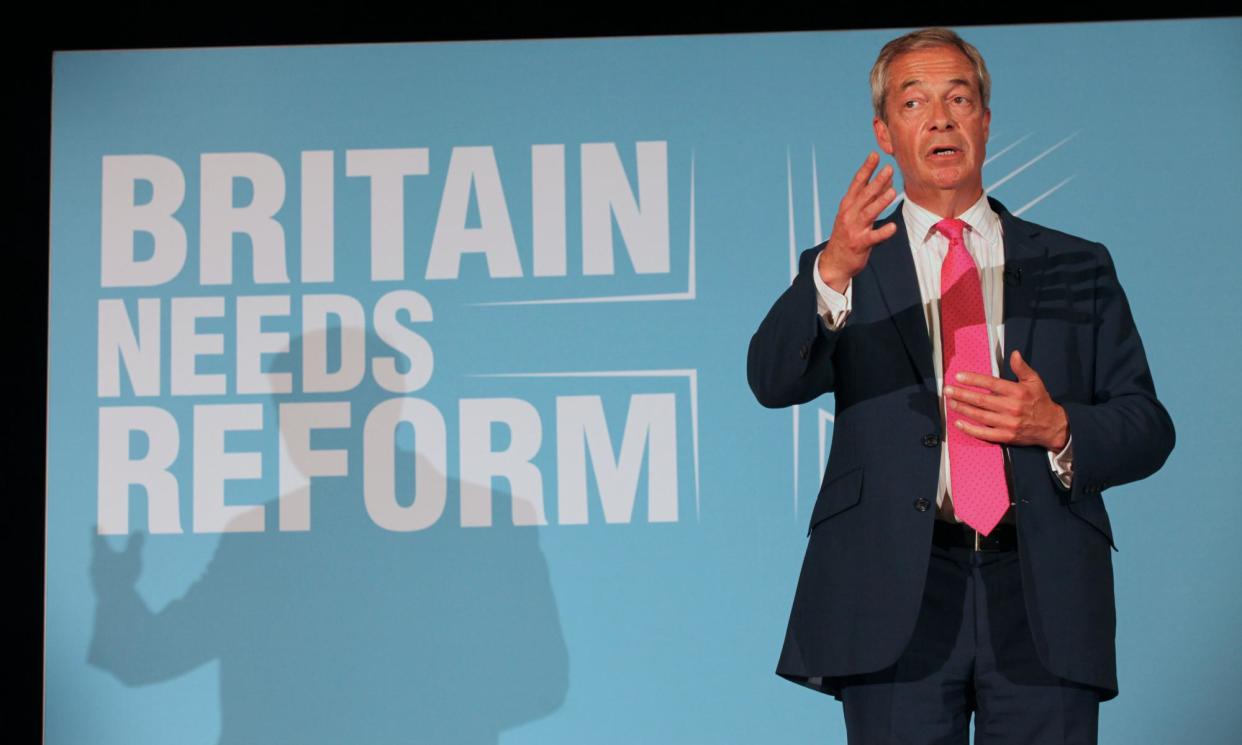

Reform UK started the campaign on an average of 11% in the polls. The return of Nigel Farage as leader, and the greater exposure that gave the party, has led to a rise in share, standing at an average of 16% with six days to go.

Should this translate into a similar vote share on polling day it would be a remarkable success for the party. At its peak in 2015 Ukip managed 12.6% of the vote.

Related: Polls mask many ‘undecideds’ and fuel Labour worry about mobilising voters

At the start of the campaign, a key part of the Conservative strategy was to squeeze the Reform vote.

Underperformance relative to expectations in byelections and high levels of uncertainty among the public about what Reform UK stood for, meant many thought the vote might be “soft”, overrepresented in polls, persuadable for the Tories or unlikely to turn out to vote.

The return of Farage at the helm not only pushed the vote share higher (though it may have risen anyway in the light of campaign difficulties for the Conservatives), but it also made those votes less likely to return to Rishi Sunak’s party.

Since an initial rise in support there seems to have been a levelling out of Reform UK’s vote share. Because the Conservative party vote share is now regularly below 20%, this produces a small number of polls where Reform UK is marginally in second place.

But there doesn’t seem to have been any further surge in support since the first of these was published two weeks ago. Over the last week, Farage has made comments suggesting the west provoked Putin into going to war in Ukraine, and more recently, Channel 4 uncovered evidence of racist remarks made by Reform canvassers in Clacton. If anything, polling over the last week has shown a slight falling back in Reform support.

The damage to the Conservatives, however, may already be done. Farage on the campaign trail and the coverage of Reform more generally after polls placed them second means the profile of the party has been raised, and with candidates in almost all seats: these are votes the Tories cannot afford to lose.

Some of the safest seats in the country look marginal under the combination of a relatively strong Reform UK vote, an improved Labour performance in key Conservative held areas and efficient tactical voting on the left.

Three in four voters in Castle Point voted for the Conservatives in 2019. Most seat level predictions from MRP models have it leaning Conservative but too close to call, while one suggests Reform UK could take it and another suggests Labour could squeeze into first place past a split vote on the right.

A split vote on the right puts high-profile Conservative MPs at risk. Liz Truss’s South West Norfolk seat had a majority of more than 50 percentage points in 2019 but is now predicted to be close on election night.

This partly reflects a much-improved Labour performance in the area, but is mostly down to Reform UK – who didn’t stand here in 2019 – being expected to gain more than 20% of the vote.

Should the Conservatives be able to win back some of the Reform UK vote it may make seats such as South West Norfolk winnable, and seats such as Castle Point safe again.

We can expect to see a final week of the campaign that focuses on trying to spook the Reform vote, trying to convince the electorate that the size of Starmer’s majority matters, and that the Labour leader and his party have radical intentions.

But those voting Reform UK are as frustrated with the Conservatives as those voting for other parties and it is not clear that any strategy could win them back.

Highly organised and efficient tactical voting to defeat incumbent Conservatives by those on the left appears to be happening at a scale not seen in Britain since 1997.

At the same time, the vote on the right is splitting in a way that is especially damaging under first past the post.

Together these could lead to electoral devastation for the Conservatives. Not long to go until we will find out.

Paula Surridge is professor of political sociology at the University of Bristol

Yahoo News

Yahoo News