Reporting on the Iran nuclear deal: 'nothing happens until everything happens'

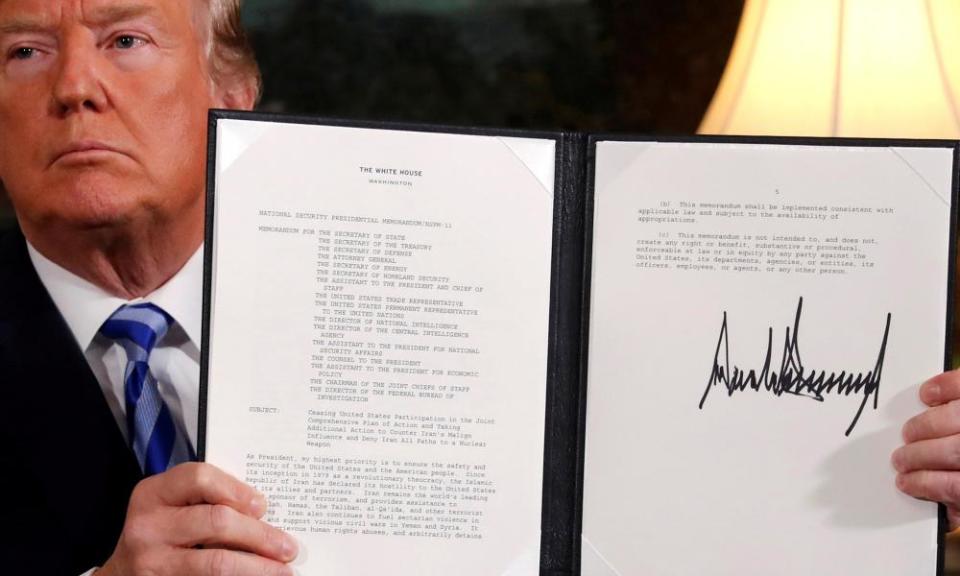

Countries tend to go to war when diplomacy fails. But Washington and Tehran are now facing off because it succeeded. It was because the 2015 nuclear deal was Barack Obama’s proudest foreign policy achievement that Donald Trump was so determined to destroy it.

The US and Iran are sliding back towards the brink of conflict. If a missile had landed a little bit differently in the course of the latest exchange of hostilities, they would probably be at war by now.

As the pendulum has swung one way and then the other, the Guardian has tried to cover the diplomacy with the same depth and emphasis as the military manoeuvres, even when it seems slow-moving and complex.

When formal talks began between the Obama administration and the new government of Hassan Rouhani in September 2013, our foreign editor, Jamie Wilson, decided we should cover the whole process in detail because of the potentially historic nature of success, and the very high price of failure.

That began for me a 22-month odyssey, trailing the diplomats from a number of countries, many a time while perched uneasily in a hotel lobby waiting for them to finish an elaborate and expensively catered meal. My colleagues and I have wondered whether the negotiations might not have moved a bit more rapidly if the parties had been booked into a Holiday Inn Express.

On the other hand, you could add up all the room service and minibar bills over the months and it would still cost less than a brace of cruise missiles. Diplomacy always seems expensive until you consider the alternative.

There was something heroic, too, about the diplomacy back then. The US secretary of state, John Kerry, and his Iranian counterpart, Mohammad Javad Zarif, regularly worked into the earlier hours and everyone else had to follow suit. All that effort in the service of compromise is hard to imagine now.

I first got drawn into the endlessly complicated world of the Iranian nuclear programme through a stroke of luck. In July 2007 I answered the phone to an Iranian diplomat with a special offer. He said a rare opportunity had opened up – would I like to be part of a small group of European and American journalists on a comprehensive tour of Iranian nuclear facilities? It felt, at the time, like finding one of Willy Wonka’s golden tickets, but with a nuclear reactor at the end of the ride in place of a chocolate factory, and Iran’s combative, messianic president at the time, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, as a very unlikely Wonka.

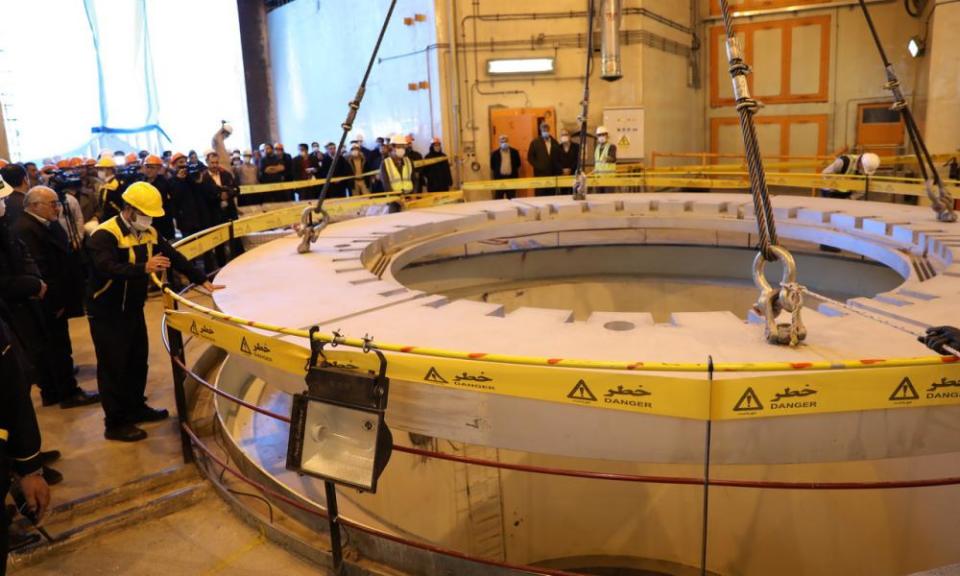

The nuclear programme had been enveloped in intrigue since 2002, when it was revealed that the government had secretly been building a uranium enrichment facility and a heavy water production plant – both possible routes to a bomb.

At the time of the call from the Iranian embassy, the UN security council was days away from passing the first of many resolutions aimed at getting Iran to halt its programme. So when we met at the airport on 19 July, it was as if we were about to enter the eye of the storm.

The mystery tour became somewhat less magical on arrival in Tehran. The foreign ministry, which had invited the eight of us, assumed it had approval from the supreme leader, but it soon became clear that the military and the Revolutionary Guards felt they had not been adequately consulted. Items were crossed off our menu like the specials at a cheap diner at closing time. The enrichment plant at Natanz? That will no longer be possible. What about the heavy water plant at Arak? Ah, that was never possible. The interview with Ahmadinejad? An awkward silence.

Perhaps the low point was driving five hours south to Isfahan to be greeted by the news that the visit to the uranium conversion plant was off, but there was a very impressive steelworks nearby.

The happy outcome of the resulting standoff between mutinous journalists and resolute officials was that we had two days to walk around the old Persian capital, surely one of the world’s most beautiful cities. When Donald Trump threatened to target Iran’s cultural sites this month, it was Isfahan I pictured in flames.

In the end, the authorities relented and we were allowed into the conversion plant (where uranium is turned into a gas that can be enriched to make it more fissile), a cluster of squat yellow-brick buildings, in the semi-desert 10 miles from Isfahan, ringed by anti-aircraft batteries at the foot of sandstone crags.

Once we were inside, staring at gleaming machinery, the underlying absurdity of our trip became evident. We had no independent way of knowing what we were looking at. It could have been a vast dishwasher for all we knew.

The one exception to our collective cluelessness was spotting the red and black wires that stretched from a concrete wall to the giant white tanks full of uranium, passing through a brass seal. This was the safeguard by which inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) hoped to detect whether any uranium was being diverted.

The great unanswered question at the time was whether Iran had a weapons programme and how advanced it was. The US administration was trying to play down reports of covert weapons plots, not wanting to derail the overall deal, while it was the inspectors at the IAEA who were suspicious.

Their suspicions about these possible military dimensions were ultimately published as an annexe to an IAEA report in November 2011. The inspectors did find evidence of weapons design studies but also found there were “no credible indications” that they had continued beyond 2009.

As part of the July 2015 nuclear deal (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA), Iran pledged to cooperate in the IAEA’s inquiries but with no fixed definition of what cooperation would look like. Its critics were also quick to point out it did not address Iran’s missile programme.

Nor did it have anything to say about human rights, an issue that was driven home to us journalists when one of our number, the Washington Post’s Jason Rezaian, and his wife, Yeganeh Salehi, were arrested in July 2014. A few days earlier we had gone for a pizza in Vienna, and he was talking enthusiastically about Tehran and Iranian food. He was held for 544 days on absurd charges of espionage.

For Rezaian – now a Washington columnist – and many of those who saw the worst side of the Islamic Republic, its cruelties are all the more reason to prevent it developing nuclear weapons, and bind it into an international agreement. For others, particularly on the American right, any deal that eased the pressure on Iran’s economy would make the west complicit in Iran’s oppression at home and aggression abroad.

In the end, all those years of diplomacy and all the delicate compromises of the JCPOA, by which the Iranians accepted nuclear limits for sanctions relief, came to naught. Tehran’s nuclear programme is expanding again, and the US and Iraq are back on the brink of conflict.

It is a chilling thought that no one in the US chain of command has the authority to stop Trump if he were to pick up the verification codes on the small plastic card (for some reason called the nuclear “biscuit”) that a US president always has close by, and order up Armageddon.

With that other extinction-level threat, the climate emergency, there is so much happening that it is impossible to keep up. But the nuclear threat is different: nothing happens until everything happens. By the time there is something substantial to report on, it could be far too late.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News