Researchers say pig experiment shows promise for humans with liver disease

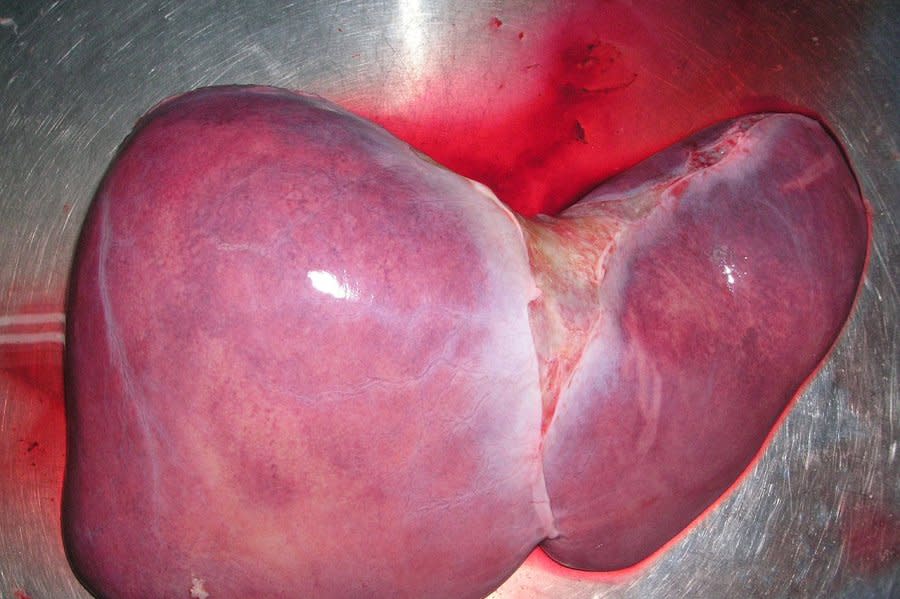

Jan. 21 (UPI) -- Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania say a pig liver attached to a human body has successfully filtered blood, creating hope for patients with liver disease.

They contend the successful experiment bodes well for the future of animal-to-human organ transplants, and could be a step toward trying the technique in patients with liver failure. The process is known as xenotransplantation.

Researchers say it points to a potential "bridge-to-transplant" approach, meaning patients could be connected to the pig liver while they wait on a transplant list for a human liver to become available, a wait that can last as long as five years.

"Across the country, more than 10,000 patients are waiting for liver transplants, and some patients run out of time waiting for a new organ," a statement from the University of Pennsylvania said Thursday.

"Initial results from a research study at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania marked a milestone in the quest for a more effective option to "bridge" critically ill patients to liver transplant.

The research team today announced the first successful completion of an experiment to circulate a recently deceased donor's blood through a genetically engineered pig liver outside their body - an effort they plan to study further in hopes of providing options to save more patients from dying while waiting for transplants."

It is significant that the pig liver was used outside the donated body, not inside. That allows doctors and researchers to better focus on the liver as it works, and also makes it easier to learn more about failing livers and how to support them.

Since the patients were brain-dead, scientists used machines to keep the blood circulating through the body and the externally attached pig liver for 72 hours during the experiment. The Penn team reported the donor's body remained stable and the pig liver showed no signs of damage.

The family donated the patient's body for research, since the organs were not deemed suitable for donation.

The method provides a way for doctors to create a "bridge" to support failing livers by doing the organ's blood-cleansing work externally, much like dialysis for failing kidneys.

Animal-to-human transplants have often failed because people's immune systems rejected the foreign organ. In this case, scientists have genetically modified the pig livers to be more "humanlike."

"I applaud them for pushing this forward," Dr. Parsia Vagefi of UT Southwestern Medical Center, said. Vagefi, not involved in the new experiment but considered knowledgeable in xenotransplantation, called the combination pig-device approach an intriguing step in efforts toward better care for liver failure.

Kidneys from genetically modified pigs have been temporarily transplanted into brain-dead donors to see how well they function, and two men received heart transplants from pigs, but both died within months.

The Food and Drug Administration is considering whether to allow a limited number of Americans who need a new organ to volunteer for studies using either pig hearts or kidneys.

More than 330,000 people require treatment for liver failure in the United States very year, according to the Penn researchers.

Currently, transplantation is the currently the only treatment cure, and "unlike patients with heart or kidney failure, there are no mechanical options available to replace the functions of diseased livers prior to transplant," the Penn researchers said.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News