Richard Sharpe, submariner who helped move under-sea Cold War tactics into the nuclear age – obituary

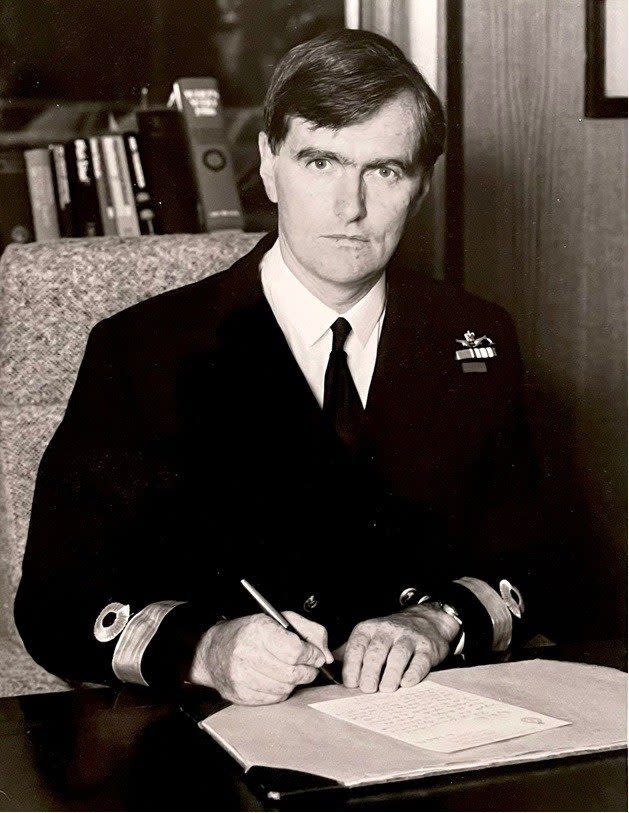

Captain Richard Sharpe, who has died aged 87, was one of Britain’s leading submariners during the Cold War and for 14 years editor of Jane’s Fighting Ships.

In March 1975, Sharpe was commanding the nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarine Courageous in the Mediterranean when he was cued to intercept a Soviet Echo-class submarine.

Sharpe later explained that detecting and remaining in contact with a Soviet submarine was the most important and obscure of the submariner’s black arts – extremely difficult, nowhere near as simple as portrayed in Cold War fiction or Hollywood films.

A simple analogy, Sharpe wrote, was crossing a field through a herd of cows in pitch darkness, when “you could hear [by sonar] munching, the swish of tails, footfalls and the occasional stomach rumble, but only a fool would claim that he knew the exact location of all the cows.

“It was difficult enough when the noise source is constant like a cavitation of a surface ship’s propeller, but you really do need first-hand experience of submarine operations to understand what is happening. Even so, you only have bearings and range analysis to help, and active sonar is no good because it instantly gives away your own position.”

Nevertheless, Sharpe covered 300 miles underwater in 17½ hours to intercept his target in a known homeward-bound lane of the Soviet northern fleet.

He detected the Echo-class boat at eight miles range and trailed it into Soviet waters covertly, remaining at a range of between 10 and 15 miles and at speeds up to 15 knots, while keeping a running commentary on his target: “Target clearing stern arcs to port. Compressed cavitation. Changing blade nosing position. Rattles and bangs. Ringing tones.”

As a result of this successful operation, Courageous won the coveted US Navy “Hook Em” award for excellence in anti-submarine warfare. For this and other submarine operations, Sharpe was appointed OBE.

Richard Grenville Sharpe was born on August 10 1936 into a naval family, and educated at Parkfield prep school in Haywards Heath. He rated the headmaster the most influential man in his early life, and left after six years with a good grounding in religion, leadership and self-discipline, without having been taught to work, but with a scholarship to Sherborne.

Sharpe joined Dartmouth as a 16-year-old cadet: always good at games, he played for the college rugby XV and cricket XI, but found the academic courses unchallenging and, though criticised for his insouciance, rose effortlessly to be a House Cadet Captain.

His 18 months as a midshipman in a cruiser in the Far East, which he likened to a modern student gap year, included some weeks seconded to the Gurkhas on jungle patrols in Malaya.

This was followed by four months in an elderly submarine based in the Clyde, and eight months at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich, doing an undemanding junior staff course and with easy access to the lights of London.

Early on, Sharpe found that “to me it was curious that although I was never in any sense a ‘clubbable’ man, I seemed effortlessly able to exercise authority over my peers.”

In the late 1950s, he chose to become a submariner, and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 found him in a boat loaned to the Royal Canadian Navy and deployed into the Atlantic to intercept Soviet merchant ships: it was a timely reminder that the Navy was not all peacetime exercises and cocktail parties.

On his return to Britain he became first lieutenant of the submarine Talent, and soon afterwards of the Singapore-based Oberon, and he saw action during Konfrontasi.

Sharpe passed the make-or-break “Perisher” course in 1966 and gained command of the conventionally propelled Malta-based boat Aeneas. Aeneas was in Haifa when the Six-Day War of June 1967 erupted and Sharpe hurriedly sailed.

Running submerged across a bay of the Ionian Sea at night, he made a rare navigational mistake. Aeneas grounded and slid inadvertently up to periscope depth. It was still dark, but the view through the periscope suggested land on all sides except astern: he hurriedly surfaced and made a stern board out of the bay.

His reconstruction showed that he had passed between two rocky headlands and had grounded on the only stretch of sand in 10 miles of coast. “You have to be lucky,” he noted.

On the passage home Aeneas took part in the filming of You Only Live Twice, when at the end of the film a submarine is shown surfacing under a yellow dinghy holding Sean Connery and his Japanese co-star.

He noted: “As this manoeuvre is impossible, what you are actually seeing is the submarine diving astern and floating the dinghy off the casing. The film is then run backwards. The two people in the dinghy were an engineer officer and a Wren borrowed from the Gibraltar garrison.”

Between 1968 and 1970 Sharpe worked in naval intelligence. He liaised with the US Navy, spent some weeks in a specially fitted intelligence-gathering submarine in the Arctic, and, when he learned that a Soviet submarine would be open to visitors in Casablanca, flew there.

He found that the submarine backwater which he had joined in the 1950s had been swept by the nuclear age into the front line of naval affairs in the Cold War.

On the nuclear engineering course at Greenwich, he stretched his brain for the first time since leaving school and found the course “a real pleasure, back to maths and science with a clearly defined end product”.

Promoted to commander in 1972, after further submarine appointments in 1977-78 Sharpe became the first operations officer of the newly created Task Force 311 at Northwood, where he successfully moved submarine warfare tactics and operational control into the nuclear age.

Sharpe’s luck changed, however, after he took command (1980-81) of the guided missile destroyer Norfolk, when he fell out with two successive senior officers who flew their flag in his ship.

He had not served in the surface fleet since he had been a midshipman, had no time for the niceties of being flag-captain, and bluntly told the first senior officer that his priority was improving the ship’s operational performance, which was not up to Sharpe’s standards.

The second senior officer did not share Sharpe’s teetotal habit at sea, and Sharpe made his disapproval clear.

As for the ship, he proved “a hard taskmaster,” said Alan West (Lord West of Spithead), the future First Sea Lord, who was Norfolk’s operations officer. “[Sharpe] didn’t suffer fools gladly, be they senior or junior to him. His absolute priority in command was the fighting capability of the ship.”

Nevertheless, two adverse reports sank his career and though he fulfilled further high-profile shore appointments, he was not promoted to admiral.

From 1987 to 2001 Sharpe edited Jane’s Fighting Ships, the encyclopaedia of navies; at this he excelled, and was admired across the world’s navies, even by those not too friendly to the West.

His list of worldwide contacts was vast, and he cultivated many collaborators among the presumed enemy, who respected his integrity.

His annual 20,000-word executive overviews were always balanced, accurate, highly detailed and yet fair and honest when highlighting defects – poor procurement decisions, for example.

He was saddened to catalogue the decline of the Royal Navy and chagrined to become better known in Washington than in London.

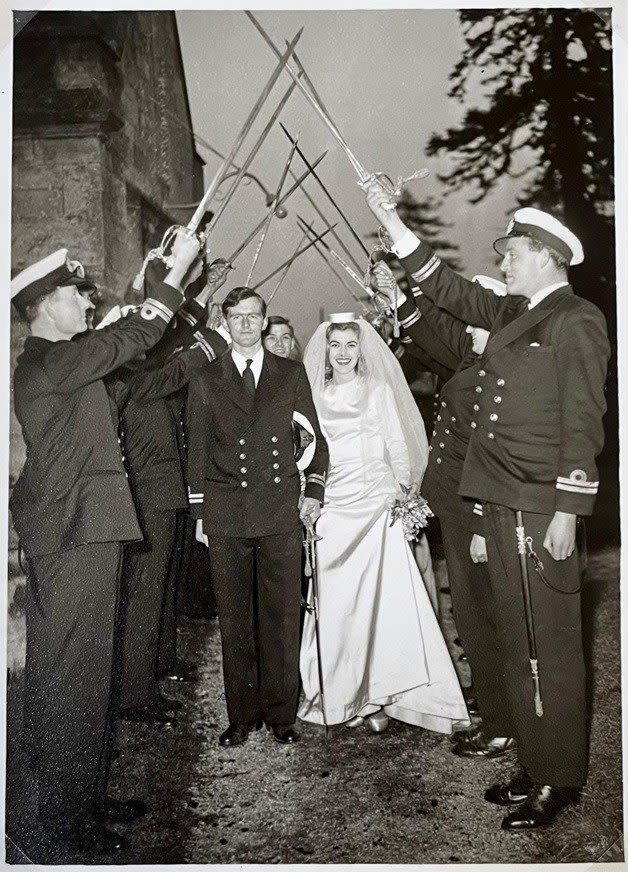

In 1961 Sharpe married Joanna Mansfield, the daughter of a naval engineer, who survives him with their two daughters and two sons.

Captain Richard Sharpe, born August 10 1936, died June 22 2024

Yahoo News

Yahoo News