The rise of white terrorists who set out to kill minorities and immigrants

One autumn afternoon in the German city of Zwickau, a woman splashed 10 litres of gasoline around her apartment, then set it on fire.

She had been dreading this day for years, hoping it wouldn’t come to this. But on 4 November 2011, it did, and she needed to act quickly to save her two cats from the flames. Their names were Lilly and Heidi. She scooped them up, put them in their carriers and walked downstairs to the street.

A passing neighbour recognised the woman by her ‘strikingly long, dark hair’. Everyone seemed to fixate on this feature, perhaps because nothing else about her appeared distinct. She was 5ft 5in, the average height of women in Germany. Her face was wide, flat, expressionless, with thin lips and grey-blue eyes. Later, when her face became famous across Germany, there was one trait that nobody seemed to use to describe her. Which was strange because it was the only one that mattered: the woman was white.

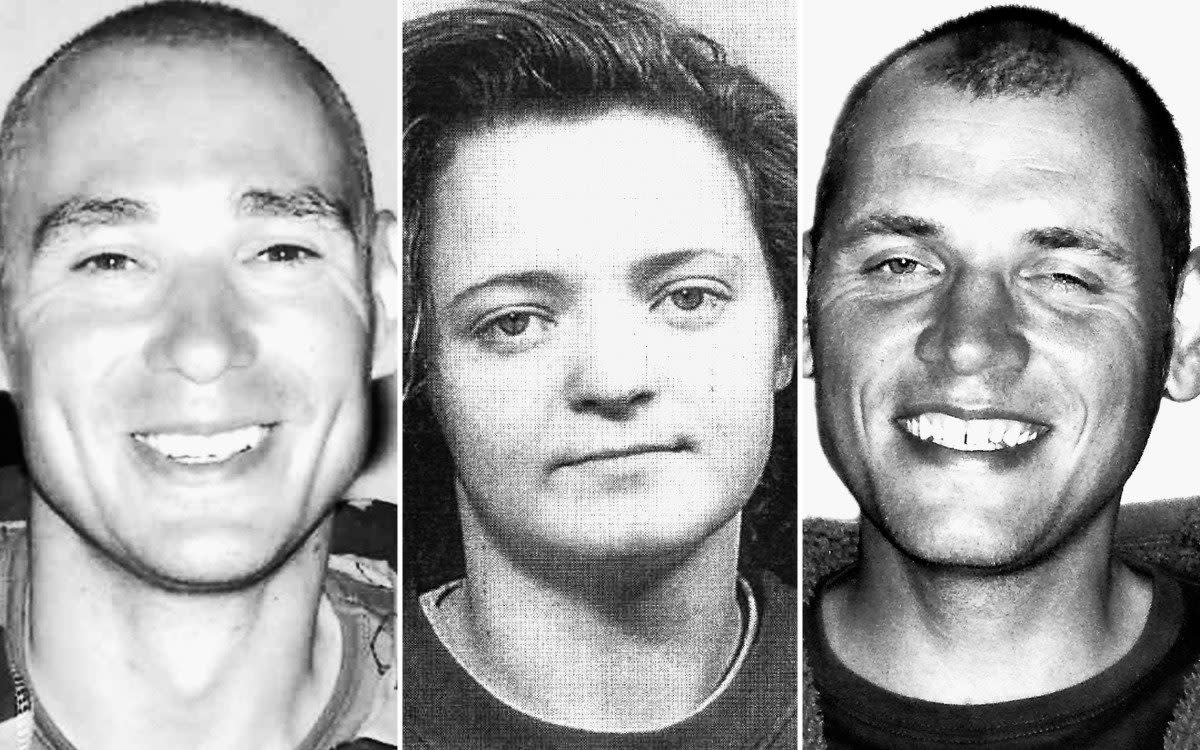

German investigators appealed for knowledge of Beate Zschäpe with this photo in 2012

She would later claim that she had waited to set the fire until the two men renovating the building’s attic left for a break, so they wouldn’t be hurt. That she had tried to warn the older lady who lived downstairs – who sometimes looked after the cats – buzzing at her door to tell her to run from the flames. She’d taken great care, her lawyer would add, to save lives the day she set the fire. The lives of other white Germans.

She wouldn’t have needed to set the fire if only the 15th bank robbery had gone as well as the 14 before it. For over a decade, her two best friends, and sometime lovers, had been robbing banks at gunpoint across Germany. In that time, they’d stolen hundreds of thousands of deutsche marks and euros, worth nearly a million dollars today. For their 15th heist they drove two hours from Zwickau to Eisenach. One wearing a gorilla mask, the other a mask from Scream, they pistol-whipped the bank manager. They pedalled away on bicycles with €72,000 in a bag, then loaded the bikes into a white camper van and drove off.

Hours passed without any sign of them. But at four minutes past noon, police spotted a white camper van parked a few miles north of the bank. Two officers approached it. Just then, they heard a gunshot, then another. The officers took cover. Then the van went up in flames.

Firefighters rushed to the scene and extinguished the blaze. Inside, lying on the floor, with a Pleter 91 submachine gun, a Czech-made semiautomatic pistol and a black handgun nearby, were the bodies of the two bank robbers, each with a bullet through the head. After setting the van on fire, one of them had shot the other, then turned the gun on himself.

When news reports began circulating about what had happened, one person in Germany knew who the men were: the white woman with the cats. She knew that they weren’t just money-driven men with a death wish. Knew that while robbing banks had been a talent of theirs, it was only a means to a more sinister end: murdering immigrants, to keep Germany white. They weren’t merely bank robbers, the woman knew – they were serial killers, terrorists. She knew it because she was one, too.

Over many years, and in many cities, they’d shot immigrants where they worked and bombed the neighbourhoods where they lived. Shot them in their corner stores, kebab stands, a hardware shop. Bombed them in a grocery store, a barbershop.

German authorities didn’t catch on to what they were doing. Perhaps they couldn’t bring themselves to believe that 60 years after the Holocaust, some white Germans could still be radicalised to the point of carrying out racist mass murder. Police blamed immigrant crime syndicates instead. And meanwhile men of Turkish and Greek background continued to be murdered one by one. 13 years passed before the trio’s violence finally ended.

After setting fire to their home – an apparent attempt to destroy evidence – the white woman ran before turning herself in. Beate Zschäpe’s five-year trial would captivate the country, and reveal that she and her friends, Uwe Mundlos and Uwe Böhnhardt, had formed the core of a much larger terrorist cell called the National Socialist Underground (NSU).

Germany’s reckoning unfolded in a courtroom in Munich packed with former far-Right skinheads and former Leftist punks. In 2018 Zschäpe was found guilty of 10 murders and being part of a terrorist group. Four supporters were also given jail terms for their roles in helping the NSU.

The case would force Germany to grapple with what drove a seemingly ordinary woman and her seemingly ordinary friends to carry out a serial assassination of innocent people – people selected for the country from which they came, their accents, the colour of their skin. It also revealed an epic failure by German law enforcement to monitor neo-Nazis or recognise their racist attacks.

I have spent eight years investigating this case and the world of Germany’s white supremacists. It quickly became apparent that the three friends were not predestined to become killers. It was the culmination of their decade-long indoctrination into Germany’s far-Right world. They didn’t radicalise alone, but as part of a white supremacist community. In eastern Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall, far-Right youths called themselves National Socialists – Nazis. They refused to participate in their nation’s collective shame. As far-Right Germans saw it, there was nothing to atone for.

For a German teenager with a penchant to provoke, nothing could be more incendiary than becoming a Nazi. Mundlos in particular relished the role, embracing anti-Semitism and expressing it through dark jokes. And by the time he and the others in the core NSU trio were coming of age, Nazi nostalgia had gained a foothold in Jena, a small city in the state of Thuringia. With his political dogma, Mundlos gave Böhnhardt’s brashness a purpose that vindicated the younger man’s predilection for violence. Those who knew Böhnhardt tended to describe him in the most explosive of terms. ‘Böhnhardt was like a bomb,’ a ‘loose cannon’ who ‘failed at school, stole gasoline and cracked cars’ then took them on joyrides.

Later, those who knew Zschäpe would be unable to put a finger on what sent her down her violent far-Right path. While she had Right-wing leanings, so did many Jena youth at the time. ‘We hated the state, foreigners, the Left – just about everything,’ her cousin Stefan would recall. The original Nazis had, too, but there was a difference: they’d chosen their far-Right path at a time when most people around them were doing the same. Millions of Germans were complicit in the Holocaust, even if not all of them participated directly. But Zschäpe embraced white supremacy at a time when her countrymen didn’t. She befriended others who did the same, and together they tiptoed across the line between extremist speech and violence.

Like the original Nazis, they blamed minorities for their ills. They despised Jews and didn’t consider them part of the white race. They derided blacks. But above all they fixated on immigrants: working-class men and women and their children, from Turkey, Vietnam, and Greece. ‘Turks are s—t, Africans are s—t – everything is s—t,’ Böhnhardt would bemoan. To the three friends, these immigrants posed an existential threat to the white nation they wanted Germany to be.

After it all ended, a country that liked to think it had atoned for its racist past would be forced to admit that violent prejudice was a thing of the present. The NSU would compel Germans to acknowledge that terrorism isn’t always Islamist or foreign. More often, it’s homegrown and white. And in an age of unparalleled mass migration, the targets of white terrorism are increasingly immigrants.

A few months after the verdict, in October 2018, Katharina König-Preuss, a German activist and politician in the Left party, followed some 700 white supremacists to the town of Apolda, Thuringia, for a neo-Nazi music show. As she photographed the event, she could see in the distance the smokestack of the Buchenwald concentration camp, which the two Uwes once visited in Nazi uniforms. It enraged her to watch these new Nazis pick up where the NSU trio had left off.

As the full gravity of the NSU’s terror had begun to sink in, Thuringia’s lawmakers had formed a committee to investigate the group and their network. König-Preuss had secured herself a seat. Although her committee didn’t have the power to indict anyone or press charges, it could still summon people to testify. König-Preuss and its other members used this power to peel back the layers of what German authorities had ignored about the NSU.

As to the question of who should be held responsible, König-Preuss’s committee concluded that Thuringia’s authorities had acted with ‘sheer indifference to finding the three fugitives’ – and that the state intelligence agency’s delays and refusals to share intelligence with police may have amounted to ‘deliberate sabotage and deliberate thwarting of the search’. It was a damning report of institutional failure. But all Thuringia’s legislature could do was compensate the NSU’s victims.

‘This monetary compensation cannot be regarded as an adequate redress,’ König-Preuss said, ‘but we would like to demonstrate that we are aware of our responsibility.’

For those whose loved ones had been murdered, the money did little to ease the pain. Ever since burying her husband in Turkey, Elif Kubaşık felt torn between two worlds. ‘Part of me is in Turkey, part of me in Germany,’ Kubaşık explained. ‘Germany is my home,’ but, ‘Germany is also the country where my husband was murdered.’ Just like Adile Şimşek, wife of Enver, another victim, Kubaşık eventually left Germany, returning to the country from which she’d emigrated decades before.

Others, such as Tülin Özüdoğru, wife of Abdurrahim, who was slain in his tailor’s shop in Nuremberg, determined to stay. Officials in Nuremberg placed a large stone engraved with the names of the murdered men in the city’s centre, one of several memorials erected by cities across Germany to commemorate the NSU’s victims. But in the weeks after the verdict, some memorials were vandalised with graffiti, presumably by the NSU’s neo-Nazi admirers.

Ayşen Taşköprü, whose brother Süleyman had been slain in their Hamburg grocery store, reflected on those admirers. ‘Instead of asking us victim families about our feelings, the journalists should rather ask the [native-born] Germans: why do you have such a hard time with people of different nationalities or skin colours? Why don’t you have the tolerance to change yourselves so that people can integrate here?’

One day when Taşköprü visited Hamburg’s city hall to do some paperwork, a clerk informed her young son that he was not German. Taşköprü laughed. She watched with amusement as her son insisted earnestly that he was. He even had a German passport to prove it. At the time Taşköprü thought little of the encounter – a mistake, nothing more. But later, it made her feel unwelcome in her own country, conjuring memories of the disregard authorities had shown to her family.

By the time Beate Zschäpe’s trial ended, the NSU was a household name in Germany. For many it was a black spot on the nation’s reputation. For more than a few, it was an incredible achievement: in the years since the NSU came to light, it had earned far-Right admirers across the country and the world. From one prison cell to another, Anders Breivik, the Norwegian terrorist who murdered 77 people in 2011, wrote a fan letter to Zschäpe, praising the NSU’s terror and calling her a ‘martyr’.

When the three white Germans began their anti-immigrant spree, white terrorism was already a global phenomenon, though few yet knew it by that name. Today, some Germans want to confront their domestic extremists. But many wish to look away. It’s a sentiment shared around the world. No one wants to believe that their neighbours may be radicalising around them, or that white terror is on the rise.

But it is. By the end of 2022, there were some 38,800 far-Right extremists in Germany, 14,000 of them potentially violent, according to the federal domestic intelligence agency – up markedly from 33,900 and 13,500 the year before. Xenophobic far-Right assaults were up 16 per cent from the previous year.

In November of last year, police arrested an 18-year-old German far-Right extremist who had obtained two rifles and ammunition and had been making threats online. Authorities allege he may have been plotting some sort of attack. Another 18-year-old was on trial last year accused of inciting far-Right attacks on the messaging service Telegram, building four homemade explosives and planning his own extremist attack. In 2020 a 23-year-old electrician who kept a copy of Hitler’s Mein Kampf was sentenced to prison for plotting to massacre ethnic and religious minorities at a synagogue or mosque.

And in December 2022, some 3,000 police and special forces officers raided 150 properties across the country and arrested 25 suspected far-Right extremists from the Reichsbürger conspiracy movement, who had been plotting to overthrow the government.

By 2023, attacks against refugees or their accommodation had almost doubled from the previous year. Having briefly earned a reputation as a haven for refugees, Germany is now struggling to protect them from violence by native-born whites. ‘There are those in the east and the west who want to see Germany as an open society’ that embraces immigrants, said Heike Kleffner, a German journalist who investigates the far Right. But there are others who would like to make Germany white. ‘This rift is played out in families, in small towns, big cities, villages. It’s a battle about defining this country.’

Earlier this year Chancellor Olaf Scholz urged Germans to oppose far-Right ‘fanatics’ and lauded the more than 1.4 million people who turned out to protest following the revelation that members of the far-Right party AfD had plotted to deport migrants and citizens of foreign heritage en masse. ‘Right-wing extremism is a major threat to our democracy and social peace. It wants to divide us, turn us against each other, and we will not allow that to happen,’ he declared.

Many Germans are demanding their government ban the AfD altogether. In January a German court cut off state funding for the neo-Nazi Die Heimat party, formerly the NPD. But any attempt to ban the AfD is likely to backfire: to even attempt it could give credence to previously unfounded AfD claims that its democratic political speech and ideas are being censored under the guise of Holocaust repentance. The country should instead focus on the very real, more immediate threat: preventing far-Right ideas from escalating into violence.

Olaf Scholz’s predecessor, Angela Merkel, was similarly outspoken against far-Right extremism – and similarly too slow to act. It was only under extreme pressure that her government removed Germany’s Right-wing intelligence chief Hans-Georg Maassen after he downplayed a wave of far-Right attacks against migrants in Chemnitz in 2018.

Today, as Germany’s economy starts to stagnate, many are calling on Scholz and the country’s other leaders to appease near-Right voters through economic stimuli or by further tightening asylum and immigration (the latter process he has already begun – in October, he told Der Spiegel, ‘We must finally deport on a large scale those who have no right to stay in Germany’). But jobs are not an antidote to deep-seated xenophobia. At best, attempts to appeal to anti-immigrant voters are merely stop-gaps until the next wave of refugees is forced to seek shelter at Germany’s door. One 2015 study in Canada even found that making concessions to far-Right voters actually ‘tended to increase far-Right attacks’.

Across the Atlantic, Donald Trump has once again been fanning the flames. ‘[Immigrants are] poisoning the blood of our country,’ he said last year, paraphrasing Nazi-era language. Over recent years Trump’s rhetoric has emboldened Germany’s far-Right. Once, while covering a rally in Dresden by the anti-immigrant Pegida movement, I watched as some 2,500 protestors shouted in unison for refugees to ‘go home’. Chants of ‘Deport them!’ echoed through the streets. People carried signs: ‘No Islam in Saxony.’ ‘Today we are tolerant. Tomorrow we are foreigners in our own country.’ ‘There is a TV crew here from Texas called Infowars,’ a speaker told the crowd. ‘They are the good ones – they are for Trump. Be nice to them.’

In the aftermath of the NSU attacks, German legislators amended the nation’s criminal code to require judges to consider racist, xenophobic, or other discriminatory motives as grounds for stricter sentences. And while the NSU trial was still underway, the Bundestag sifted through some 12,000 files, questioned more than 100 witnesses, and published thousands of pages of documents about the group’s terrorist spree.

But the resulting 1,300-page report didn’t mention that institutional racism was to blame for the authorities’ failure. Neither did two subsequent, in-depth reports.

The NSU case found its way into literature, art, entertainment and popular culture. In 2018 a German playwright named Michael Ruf created the NSU Monologues, in which actors recount the stories of Adile Şimşek, Elif Kubaşık and Ismail Yozgat, whose son Halit was murdered, in their own words. The play is a living memory of the carnage wrought by the NSU. It is also a warning of what white nationalism can do to a nation.

But none of this has achieved what the victims’ families want most: to ensure that German authorities reform so that something like this can never happen again. To that end, some of the families feel disappointed: not one police officer, intelligence agent or informant was charged for negligence for failing to stop, or for enabling, the white terror of the NSU.

Beyond Germany: White Terror in the US and elsewhere

Since 9/11, more people in the United States have been murdered by far-Right extremists than by any other kind, including Islamist ones. In all, they have killed at least 134 people in the US; jihadists, 107; ideological misogynists, 17; and black nationalists, 13.

The year President Donald Trump took office, American white supremacists murdered twice as many people as the year before. In Christchurch, New Zealand, in 2019, minutes before a white man began shooting up mosques, he circulated a manifesto that praised Trump as ‘a symbol of renewed white identity and common purpose’. He wasn’t the first white man to find common purpose in terrorising immigrants and racial minorities, Muslims and Jews. And he wouldn’t be the last. Another white terrorist found it in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where he murdered three young Jordanian-and Syrian-Americans in their home in 2015. In 2017, another one found it in Kansas, where he yelled at two Indian engineers, calling them ‘terrorists’ and screaming at them to ‘get out of my country’, before shooting them.

Another white terrorist found it at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh in 2018, killing 11 people and injuring six. Another found it as he hunted Mexicans in the aisles of a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, slaughtering 23 people. Another one found it in a black neighbourhood in Buffalo, New York, where he entered a grocery store and shot 13 people – almost all of them black – killing 10. Another found it in a shop in Jacksonville, Florida, where, on the 60th anniversary of Dr Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech, in August 2023, he killed three black shoppers, and then himself.

Just as in Germany, most terrorists who strike in the United States are homegrown and white. — Jacob Kushner

Abridged extracts from White Terror: A True Story of Murder, Bombings and Germany’s Far Right, by Jacob Kushner, out on 9 May (Mudlark, £25); pre-order at Telegraph Bookshop

Yahoo News

Yahoo News