Robert Plant’s teenage obsessions: ‘Stourbridge was our Beverly Hills’

The Welsh landscape

I was an only child until I was 11, so my childhood was spent in this blissful otherworldly state, cycling with my dad through the Welsh borders, visiting castles and churches. Just 30 to 40 miles from the Black Country, everything would change: the landscape, language, folklore and the remoteness of spirits. As a teenager, I spent so much time riding my bicycle into that area and taking photographs. I was drawn to Bron-Yr-Aur, the cottage [immortalised in Led Zeppelin’s Bron-Y-Aur Stomp] where I holidayed with my folks and from where I would ultimately introduce [guitarist] Jimmy Page to Snowdonia. Meanwhile, at school, the other kids had big brothers and sisters who were awash with amazing, exotic, risque stories, all playing out to the hits of 1961. All this was the beginning of it for me.

Stourbridge town hall

I pushed my stamp collection to one side and found myself cycling into Stourbridge in the West Midlands most nights, and working in Woolworth’s every weekend to be able to buy a ticket to Stourbridge town hall for five shillings. The curtain would pull back and there would be Gene Vincent, Screaming Lord Sutch or the Pretty Things. Everything seemed otherworldly, even the gels used in the spotlights. Suddenly my mates in the lunatic fringe at King Edward VI grammar school had pointed shoes and slicked-back hair and the girls wore petticoats. Everyone was getting ready to become mods, and all this played out among blood, sweat and cheap perfume on a maple sprung dancefloor. To me, Stourbridge was the Beverly Hills of the Black Country. There were three kingdoms: rockers with bikes and Gene Vincent, jazz beatniks with modern jazz quartets and fancy Albert Camus books, and then the blues and folk movement listening to Leadbelly and such. I was obsessed with it all, so became any one of those throughout the week. One night, my schoolmates asked me to sing in their band, the Jurymen, at some gig in Swadlincote. I looked down over the audience into the eyes of true love: to my right, to my left, and a blonde true love over there. Oh, dear … From that moment, I knew what I wanted to do.

Rhythm and blues

I was lusty to get away from family life, so ran away from home a couple of times and then left home, school and college in quick succession. I was singing R&B very badly and living with the families of bands I was in, such as the Crawling King Snakes or Listen. I cut my first record [Listen’s You Better Run, 1966] for CBS, which felt amazing. I’d met my future wife, Maureen, at a Georgie Fame gig and was working at the Plaza ballrooms in Birmingham. I was the opening act. Then I’d rush off and put on a suit to introduce the top acts. One night, I introduced Little Stevie Wonder, who was the same age as me. He sang I Call It Pretty Music But the Old People Call It the Blues, an explosion of craft, skill and soul. I ended up at all-nighters doing leapers [amphetamines] and jumping around, working behind the Coca-Cola machine and sometimes not sleeping for days. I saw Ike and Tina Turner. Before the gloss, she was incredible, primeval. Across the room, Buddy Guy was dropping his Stratocaster on the stage in the chord of A, then I’d hang out with the rude boys at the Zoco Chico West Indian cafe, listening to Delroy Wilson. I was roaring through that whole spectacular mod, underground, black R&B culture. If the mods had been into Showaddywaddy or something it could have ended everything.

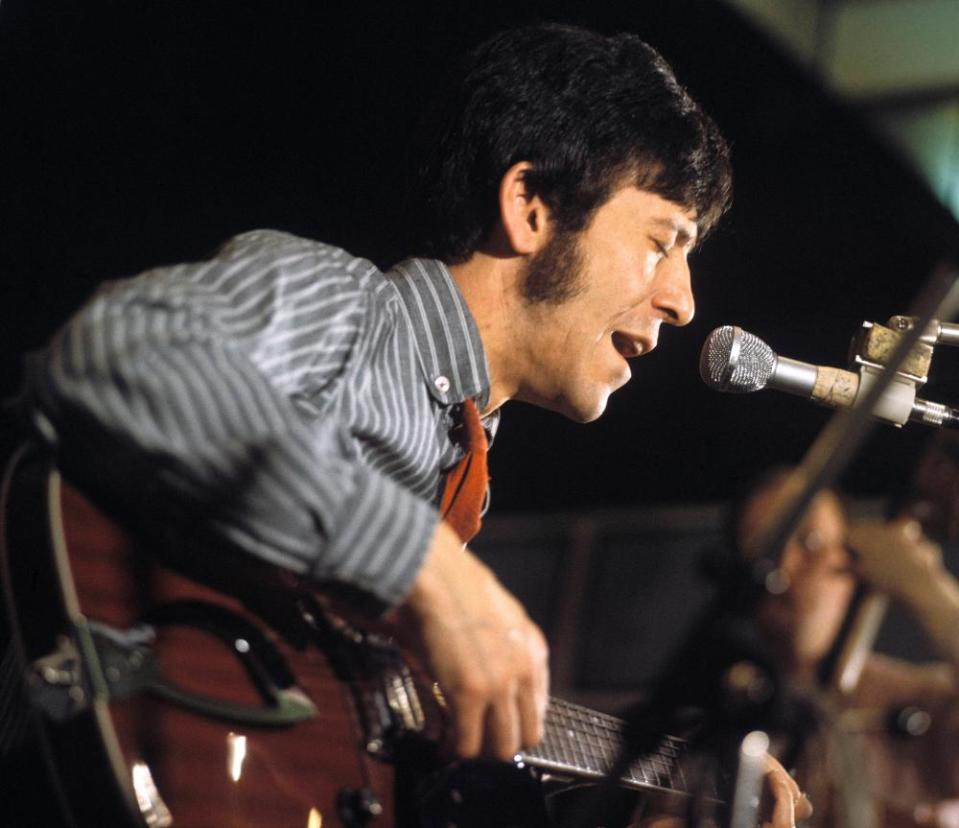

Alexis Korner

I wasn’t earning any money, so ended up tarmacking West Bromwich high street with other musicians walking past going: “Looks like you’re gonna be a big star!” Then I went to see [British bluesman] Alexis Korner play in Birmingham. After one song, I asked if I could play harmonica with him, and he said: “Come and see me in the break.” Then it was: “Play me a bit of Sonny Boy [Williamson] … OK, get up in the second half.” Suddenly I became Alexis Korner’s harmonica player, and carried his bag in and out of gigs. I learned so much from him. He wasn’t Johnny Guitar Watson or Jimi Hendrix, but carried the whole ethos of blues and made it palatable for people who weren’t going to get the Blind Lemon Jefferson stuff on the Riverside label. When I had nowhere to live, I stayed at Alexis’s place on Queensway in London. He’d say: “Goodnight, Robert. You’re the second person on that couch this month. It was Muddy Waters before you.”

John ‘Bonzo’ Bonham

Steve Marriott, Steve Winwood, Cliff Bennett, Terry Farlowe and Terry Reid could really sing. Terry [Reid, who turned down Led Zeppelin, recommending Plant instead] was like a brother, and we ended up doing shows together. We’d sing [Donovan’s] Season of the Witch at some debs’ ball in Chelsea and then attack the kitchen. Jimmy Page and [future Led Zeppelin manager] Peter Grant came to see me, by which time I was in Band of Joy with the drummer from the Crawling King Snakes. I’d first met Bonzo at the Plazas when he came up and said: “You’re all right, but you’d be twice as good if you had the best drummer in the world.” I said: “I’ve already got that, who are you?” That became the tone of our friendship all the way through Zeppelin: we loved each other, but would always have a shoulder-to-shoulder. Before Zeppelin, I always knew when he had a better offer because he’d get his drums out of the van to clean them. He made such a contribution to the extreme power that I was able to switch on because he was thundering behind me, growling away.

Wolverhampton Wanderers

I have followed Wolves for 65 years; it’s a place of solace, where you know it’s not always going to be plain sailing. It started when my dad took me to see them play Liverpool and I thought [Wolves centre half] Billy Wright waved at me. I didn’t take into account that there were 15,000 people standing on that side of the ground. Years later, I met Billy at [children’s TV show] Tiswas when he was head of ATV sport. It was like Zeppelin meeting Elvis. I told Billy I was the kid he waved at in the Waterloo Road stand. He clasped my shoulder and said: “Of course I did, Robert.” I’ve had abuse following Wolves and my daughter Carmen still reminds me that I took her to places such as Ayresome Park in Middlesbrough, when we’d be cowering in someone’s porch while there was a riot going on. I sometimes play Wolves chants before gigs. The audience are sitting in dark, shadowed homage preparing for this wonderful moment, and suddenly it goes: “Who are ya?!” As a greying, ageing, ex-rock god figurehead, I find the important thing is to have a great, humorous life.

• Robert Plant’s podcast Digging Deep Series 4 begins on 24 May, available everywhere including Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Amazon.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News