Roland Dumas, suave French Foreign Minister and Mitterrand ally who became embroiled in scandal – obituary

Roland Dumas, who has died aged 101, was a French resistant, lawyer and politician whose career was borne relentlessly upwards by his great friendships with Pablo Picasso and François Mitterrand; ultimately, however, he was brought down by the suspicion that he considered the civilised expression of power best left to a small number of highly-cultured men such as himself.

This trait was most evident during the five years, from 1988, that he was foreign minister. Dumas’s appointment to the Quai d’Orsay had in itself annoyed staff there, who felt that the job ought to have gone to a ministry insider.

Once in place, Dumas proceeded further to vex his colleagues by making it clear that he was intent on working not in their interests, but in those of President Mitterrand. Sometimes, for days on end, diplomats had no idea where to find their boss, who would be off on a private assignment for the Elysée.

As often as not, this would be a book shopping expedition with Mitterrand – a secretive, private man of few close friends, who seemed to recognise and appreciate similar qualities in Dumas. If the pair were not browsing antique tomes, they could be found strolling through galleries around town. Sometimes, it was rumoured, their cultural excursions were primarily to appreciate the female form.

But Dumas’s exceptional charm was not just reserved for Mitterrand. He also forged close personal ties with his counterparts in Britain and Germany – Geoffrey Howe and Hans-Dietrich Genscher. These relationships were critical in a notable period that included the collapse of the Soviet Union, Maastricht Treaty negotiations, German reunification and the first Gulf War.

Yet – despite his talents and the significance of these events – Dumas’s term at the Quai d’Orsay will be best remembered for his involvement in a corruption scandal that emerged after he had left office.

The Elf Affair, as it became known, gripped France throughout much of the 1990s, when it became clear that hundreds of millions of pounds had disappeared from the state-owned oil company, Elf, and that this money had been used to finance political parties in France, as well as grease the wheels of a shadow foreign policy abroad. Those pulling the strings of this state-sanctioned system of graft, meanwhile, were revealed to be living the high life, bankrolled by Elf.

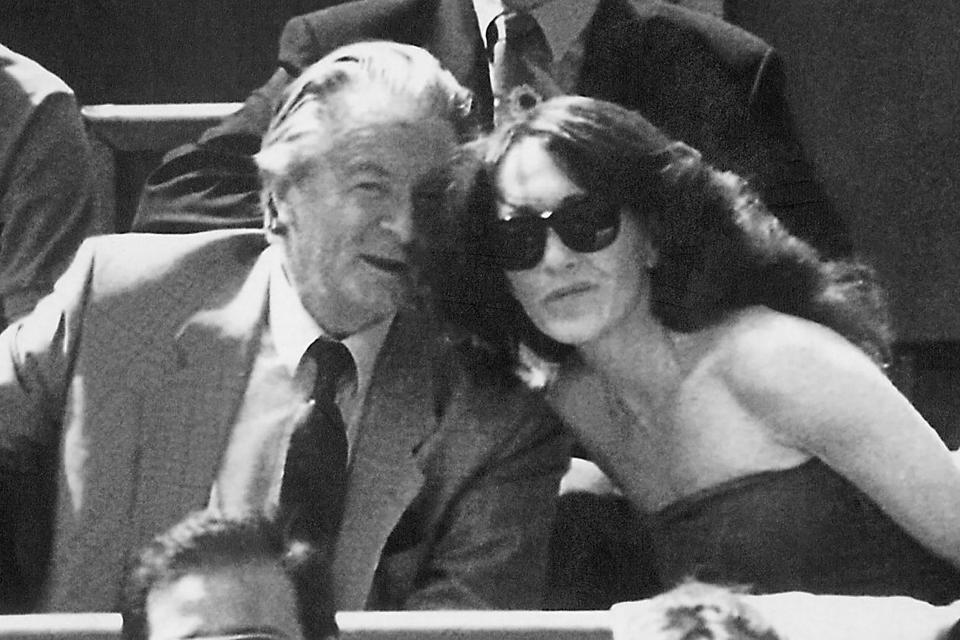

One of these people was a glamorous, twice-married brunette called Christine Deviers-Joncour, who was recruited by the oil company’s bosses in 1989. Over the next four years she was given a generous salary, unlimited expense account, and the use of a fabulous apartment on the Left Bank in Paris.

To magistrates investigating the case it was hard to avoid the conclusion that her principal qualification for this job was the fact that, in 1988, she had met the handsome, erudite foreign minister, Roland Dumas, and that, despite the 20 year gap in age, the two had become lovers.

Their relationship was critical because a French company, Thomson, had proposed a $2.7 billion dollar deal to sell six naval frigates to Taiwan – a deal Dumas had initially opposed because he thought it would damage France’s relationship with China. Two years later, in 1991, he changed his mind, and Mitterrand gave the lucrative sale the green light.

Magistrates discovered that Elf had been used as a go-between to facilitate the arms deal, and investigators focused on deposits made into Dumas’s bank account to see whether money was paid to him by Deviers-Joncour to get him to approve it.

What was certain was that, during their relationship, his mistress gave Dumas several presents which, prosecutors claimed, he must have known were financed illicitly. These included statuettes worth tens of thousands of pounds and, most damagingly, a pair of handmade Berluti boots costing £1,200.

More than anything, it was the suspicion that the silver-haired Socialist minister had trampled the law under such luxurious footware that proved injurious to his reputation. Nor did it help that, as rumour and allegations of misdeeds swirled, he had assumed the august role of president of France’s highest court.

As a former resistant, Dumas’s reputation was crucial to him. At his corruption trial in 2001 he appealed directly to the court. “To run the risk of dishonour at my age is unbearable,” he said. “It is heartbreaking for me to find myself here before the court after a life which began in misfortune and has always been characterised by hard work.” It did no good, however, and he was sentenced to two and a half years in jail, with two years suspended, and fined almost £100,000.

When, in January 2003, he was cleared on appeal, he released a book which aimed to reclaim the honour of which he felt he had been unfairly stripped. By then he was 80, and he lashed out at a cynical collusion between magistrates, politicians and the press.

But some readers could not escape the conclusion that such collusion and subterfuge was precisely how many things had got done during Mitterrand’s reign – a reign in which Dumas had been a key courtier.

As the New Yorker had noted in an earlier profile: “Even in a society accustomed to taking personal freedom for granted, Roland Dumas stands out for having done largely as he pleased with his life.” Dumas seemed to concur. “In politics I’m not a complete professional,” he admitted. “I have freedom. Everything in life is precious.”

He was born on August 23 1922 in Limoges, the son of Georges and Elisabeth Dumas. His father was a tax official and reservist captain who had fought in the Great War and whom Roland grew to admire greatly as he grew up. “I wanted to be like him in all senses,” he said. Roland’s early family life was stable and idyllic to the point that, despite his future achievements, he later looked back and suggested that “everything else has been derisory by comparison.”

He was educated at the lycée in his home town before moving to Lyon, where he studied at a Roman Catholic college. It was while in the city that he started helping the Resistance, of which his father had already become an active member.

His activities were often symbolic: the distribution of Free French literature, or the staging of a protest against a performance by the Berlin Philharmonic, which got him jailed for three weeks. But he also helped Jews flee France into Switzerland, perhaps encouraged by his father, who sheltered Jews at his home.

After his imprisonment ended, Dumas briefly joined a Maquis group in the Limousin, before moving to Paris to study Law, all the while retaining his Resistance contacts. On arriving in the capital he was, he said, provided with money and false papers by a friend of his father’s called Jean Mons. He also began singing with Marguerite Dubois, the daughter of another friend of Georges Dumas’s, and discovered a tenor voice so fine that he would later consider pursuing a career in music.

It was through the Dubois family that Dumas learned the news that was to change his life, when Marguerite Dubois’s father, Eugene, told him that Georges Dumas had been executed by the Nazis.

Dumas père had been arrested by the Gestapo on March 24 1944. Two days later he was one of 25 Resistants shot in the Périgord town of Brantöme. The Occupation in general and his family’s sacrifices in particular were to mark Roland Dumas forever; thereafter his reverence for personal honour was exceeded only by a determination to pursue personal “freedom”.

This latter trait guided Dumas in all things. Alhough he excelled as a lawyer and politician, his subservience to established rules or to the nominal hierarchy of political parties always seemed superficial at best.

It was for this reason that he eventually decided against both music and a career in journalism, the latter of which he dabbled in while pursuing a number of degrees in the late 1940s (one of which was financed by a British grant to the children of fallen Resistance heroes). “As a journalist I wasn’t my own master,” he said. As for musicians, he fretted, they had “many obligations”. Instead, he said, he “wanted to be free – free to do politics”.

But he needed money, and found in the Law a profession libérale which could provide him with capital without trammelling him unduly. After a successful case defending a Resistance leader accused of summarily executing collaborators at the end of the war, Dumas in 1954 joined the defence team for his father’s old friend Jean Mons, then a senior figure at the ministry of defence. Mons, himself a former resistant, had become implicated in the leaking of classified material, but ultimately was cleared of wrongdoing.

The case brought Dumas to the attention of senior government figures, notably the interior minister, François Mitterrand, and the political strand of his career was launched. Two years later, in 1956, Dumas was elected to the Assemblée Nationale for Mitterrand’s Union Démocratique et Socialiste de la Résistance.

Dumas’s political allegiance was never in doubt – its connections with the Nazi Occupation ruled out any possibility of him working with the Right. But he was no ideologue. “For him, the only thing on the Left was the steering wheel of his Porsche,” one diplomat remarked later. Personal loyalties were more important, and in 1959 Dumas made a fierce demonstration of loyalty to Mitterrand that would transform his career.

This occurred when Mitterrand was caught up in a scandal which nearly ended his own political ascent, when a man named Robert Pesquet informed the future president that he had been hired by Algerian militants to assassinate him. Pesquet claimed not to want to fulfil this commission, but feared retribution if he was not seen to make an effort. Accordingly, Mitterrand agreed to a hoax in which he would abandon his car at a certain point, which would then be sprayed with bullets.

Mitterrand was initially hailed a hero who had narrowly dodged death. But then Pesquet turned betrayer and produced evidence of Mitterrand’s complicity in the hoax. Suddenly the politician became a figure of fun who had seemed to want to boost his standing with a ludicrously-fabricated murder plot. Many friends and allies deserted him, but Dumas did not, publicly taking Mitterrand’s side in the Assemblé. His steadfastness was not forgotten.

But politics were not enough to occupy a man of Dumas’s butterfly temperament; he had also found time to become the lawyer for the celebrated Gallery Leiris, whose owner, Zette Leiris, found him “knowledgeable, very charming, and very alive”. It was through the gallery that Dumas was introduced to Picasso, who in the mid-1960s was looking for a new lawyer.

Dumas represented Picasso from 1966 and the two men got on well, with Picasso making several sketches and one painting of him. But the most onerous legal duties from the relationship began after the artist’s death in 1973. Dumas called Picasso “a fundamentally timid man... who couldn’t make a will, because it raised the question of his death”.

Dying intestate, Picasso left an enormous legacy (2,000 paintings, 7,000 drawings among much else) that took seven years to catalogue and value, with six heirs and the French state all competing for a portion of the artistic treasure trove. Others involved in the process said that, during this time, Dumas displayed his extraordinary talent for diplomacy – calming and cajoling the Picasso family into an agreement that prevented an even more bitter and protracted legal war.

By then Dumas was also in the process of resolving the other great legal hangover of Picasso’s career – the fate of Guernica (1937), which Picasso had been commissioned to paint by Republicans during the Spanish Civil War. The artist was determined that the painting, on extended loan in New York, should not be returned to Spain until democracy was re-established in the country. When asked who should decide if Spain had met this standard, Picasso designated Dumas.

Following Franco’s death in 1975, Spain began to lobby for the return of the picture. Once content that the democratic bar had been reached, Dumas had to decide where the picture should hang – Madrid, Barcelona or Guernica itself. Finally, in 1981, it was installed at the Prado.

The case had seemed to call on all of Dumas’s talents – diplomacy, political instinct, artistic discernment and sensitivity to individuals’ concerns – and he was rewarded with wealth, renown, and Spain’s highest honour, the Order of Isabel la Católica. By then he had also collected, through his connection to artists via Picasso, a substantial art collection, including works by Giacometti, Chagal and, inevitably, Picasso himself.

Dumas’s principal legal client besides Picasso was considerably less glamorous than the artist. But in its way Le Canard Enchaîné, an investigative and satirical newspaper which continues to run irreverently embarrassing exposés of Establishment figures, mirrored Dumas’s own determination not be bound by the rules. Le Canard’s stories often attracted legal problems, and when, in 1969, its editorial board began looking for a new lawyer “with charm as well as ability”, they quickly settled on Dumas.

He won his first case with the paper, against a powerful government figure rumoured to be in charge of France’s secret services. It was a victory over the odds, success which Dumas took further when Le Canard turned the tables and sued the state after a cartoonist walked in on government agents planting listening bugs in the paper’s offices. Several other high profile cases followed, and Dumas’s legal career was assured.

In the 1970s, by contrast, his political career seemed on the wane. He had already lost and regained his parliamentary seat once when he was ejected from parliament for the second time as De Gaulle crushed the Left following les événements of 1968. He dutifully joined the Socialist Party as Mitterrand assumed its helm in 1971 however, and when, a decade later, Mitterrand was elected France’s president, Dumas was again elected to parliament.

Many, Dumas included, presumed his undoubted talent and long-standing friendship with Mitterrand would be rewarded with a ministerial post. That was not to be the case. This exclusion was undoubtedly a bitter blow for Dumas, but the sting did not last long.

In 1983 he was appointed Minister of European affairs, largely to sort out the thorny issue of Britain’s contribution to the EEC budget. As ever he did not approach the issue in adversarial manner. Instead he employed the tactic that had worked so well in reconciling the factions warring over the Picasso legacy – finding a point of common interest between all parties and convincing them to adopt it.

His work won universal admiration and it was typical of Dumas that, despite his staffers reporting his Herculean capacity for work, other delegations described him making the mastery of his brief seem almost boringly easy. He spoke a host of languages, once interpreting for Helmut Kohl and Margaret Thatcher (like everyone else, she thought Dumas “charming”), as they argued with each other.

His most significant failure was in negotiating a deal with Muammar Gaddafi of Libya, in which both Libya and France agreed to withdraw their troops from Chad and prevent a war there. French troops did so, Libya’s soldiers stayed on, humiliating Mitterrand. This reverse, however, did not prevent Dumas’s appointment as Foreign Minister in December 1984, a post in which he served until 1986 and then resumed after Mitterrand’s re-election in 1988.

Thereafter he was kept busy with the reunification of Germany and the collapse of the Soviet Union, though he did again find Libya a source of political discomfort – particularly after France returned Libyan-owned Mirage fighter jets to the north-African country. Three French hostages held by Libyan-sponsored terrorists travelled in the other direction. Dumas’s praise of Gaddafi’s “noble and humanitarian gesture” rankled with many.

He lost his parliamentary job for the last time in 1993, but in 1995 Mitterrand appointed him Président du Conseil Constitutionnel. Under his leadership the country’s highest court pronounced in favour of immunity from prosecution for French presidents while in office. After two years, however, Dumas’s name began to crop up in the Elf Affair. By 1999 he was forced to resign as the case threatened to overwhelm him.

Though he was cleared of charges in the Elf case he was, ultimately, convicted of mishandling the estate of the sculptor Alberto Giacometti. Dumas had arranged a sale of Giacometti works to help settle duties after the death of the sculptor’s widow, Annette. But prosecutors alleged that 1.2 million euros from the sale were withheld by the auctioneer and that a sum of several hundred thousand euros had been paid into Dumas’s account shortly afterwards. Dumas was handed a 12-month suspended sentence and 150,000 euro fine.

Conviction and the threat of jail represented an inglorious end to a life which he had always insisted was founded on honour and freedom. But by then Dumas watchers had already long made up their minds about him.

To his fans he was a man of inordinate talent who found solutions where others could not, whose capacity to charm on a personal level was matched by a lofty intelligence that could analyse and direct strategy on the international stage. To his critics he was an arrogant dilettante of ability but little substance who lived a charmed life during he which he somehow managed to behave just as wished until his belated but well-deserved comeuppance.

Dumas himself seemed little affected by his last judicial reversal, and increasingly abandoned his carefully cultivated air of mystery to appear, sage-like, on television, drawing on his experience to commentate on domestic and foreign affairs.

Roland Dumas’s marriage to Theodroa Voultepsis was dissolved; he subsequently married Anne-Marie Lillet, with whom he had a daughter and two sons. To the end of his life he made an annual pilgrimage to the site of the execution of his father.

Roland Dumas, born August 23 1922, died July 3 2024

Yahoo News

Yahoo News