Roy Cohn: Ruthless McCarthy lieutenant-turned-Trump mentor so universally loathed he was ‘a new strain of sonofab****’

He was a lawyer with a two-syllable name, a colourfully complicated personal life and a Rasputin-like grip on United States politics – especially in New York.

The very mention of Roy Cohn during his four decades of headline ubiquity could spark anything from anger to hatred to fear; his shadowy legend persists nearly 40 years after the death of a man dubbed a “new strain of sonofabitch” – by his own autobiography co-author, no less.

Now those that missed Cohn’s infamous antics the first time around will meet him in a new film premiering at Cannes, The Apprentice, by director Ali Abbasi. Pop culture darling Jeremy Strong from Succession stars as Cohn, the Joseph McCarthy lieutenant who created the blueprint that Donald Trump followed all the way to the presidency.

The Deadline announcement calls the first Trump biopic “a mentor-protege story,” with a film’s summary on the Cannes site explaining that it “charts a young Donald Trump’s ascent to power through a Faustian deal with the influential right-wing lawyer and political fixer” himself. A still of the film shows the pair in the back of a town car, Strong as Cohn fixing his steely eyes on Sebastian Stan, who plays Trump.

Trump’s name inspires a range of emotions mirroring those elicited by any mention of Cohn. The future 45th president was guided and represented by the Bronx-raised lawyer during his ascent through the ranks of New York business and society; one need only give a cursory read of Cohn’s eponymous memoir to see Trumpisms.

The word “losers?” It’s on the third page of Chapter One. “Lousy?” It’s on Page 37.

“Donald Trump is Roy Cohn,” Matthew Tyrnauer, director of the 2019 documentary Where’s My Roy Cohn, said in an interview with NPR the year of his film’s release.

“He completely absorbed all of the lessons of Cohn, which were attack, always double down, accuse your accusers of what you are guilty of, and winning is everything,” Tyrnauer continued. “And Trump absorbed these lessons and has applied them in every aspect of his life and career.”

Cohn worked on his eponymous memoir with journalist Sidney Zion, who notes a “point of order” after Chapter 11 – when the book turns “from Roy Cohn telling the Roy Cohn Story to me telling Roy Cohn stories” as the lawyer faded with illness.

Even before Cohn gleefully recounted within the book’s pages his legal battles against indictments – (sound familiar?) – he also took a stab at imagining his own obituary on the same opening page. He used words like “notorious,” “explorer” and “writer.”

Cohn rightly predicted that most obituaries would recall him as “McCarthy Investigations Aide” – because, years before Cohn’s tutelage of Trump, he first became a household name and tabloid staple through his pivotal role in one of America’s greatest witch-hunts.

The McCarthy hearings may have launched Cohn into adversarial infamy, but his shrewd and manipulative brand of power-brokering had its roots far earlier. The only child of a well-connected Bronx judge and doting Jewish mother, Cohn wrote in his memoir that “virtually every heavy hitter in politics, law, the judiciary made it to our apartment while I was growing up.

“Looking back on it now, I guess I always took for granted that I’d be around powerful people; it was normal, which may help explain why in this way at least my life never changed,” he continued.

In that way, as well, his life was unusual from the start – and he made quick work of ensuring the continuation of that markedly different streak. Cohn finished high school early and completed both undergraduate and law degrees before the age of 20 – still too young to be eligible to pass the bar exam. Once he did, however, he finangled a job as an assistant US attorney in New York. He made a name for himself as ambitious and fiercely clever by prosecuting such high-profile anti-Communist cases as the Rosenbergs, the couple convicted in 1951 of spying for the Soviet Union and subsequently sent to the electric chair.

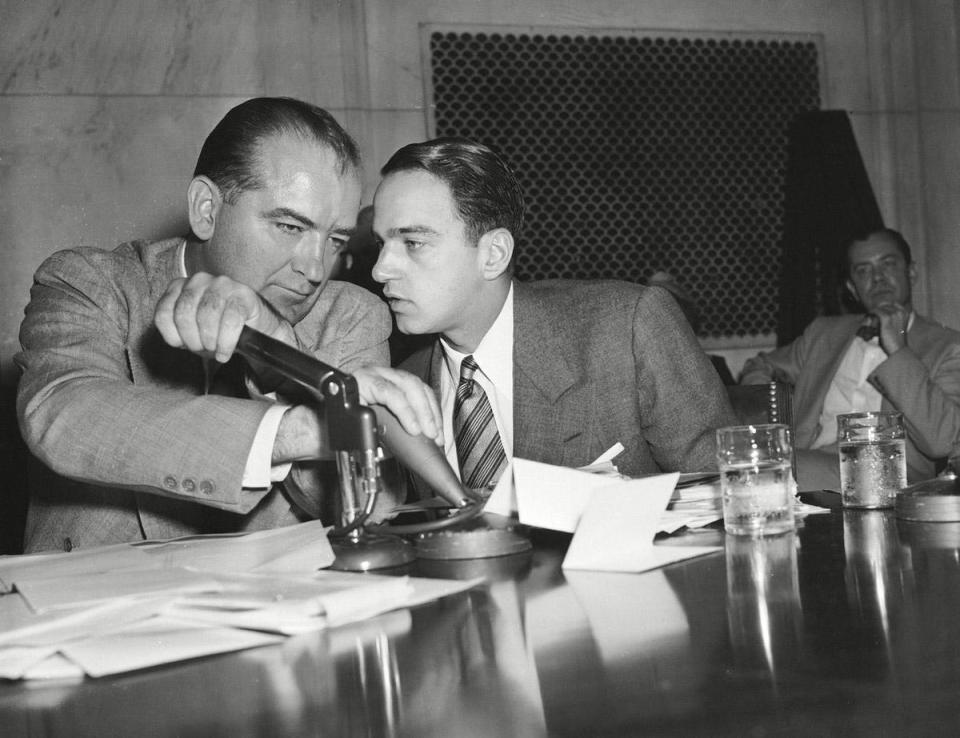

Cohn’s “brand of anti-Communism,” as his New York Times obituary would one day describe it, soon landed him a job as chief counsel to Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s investigations subcommittee, which further thrust him into the national spotlight amidst the crusades of the day – though not always for favourable reasons.

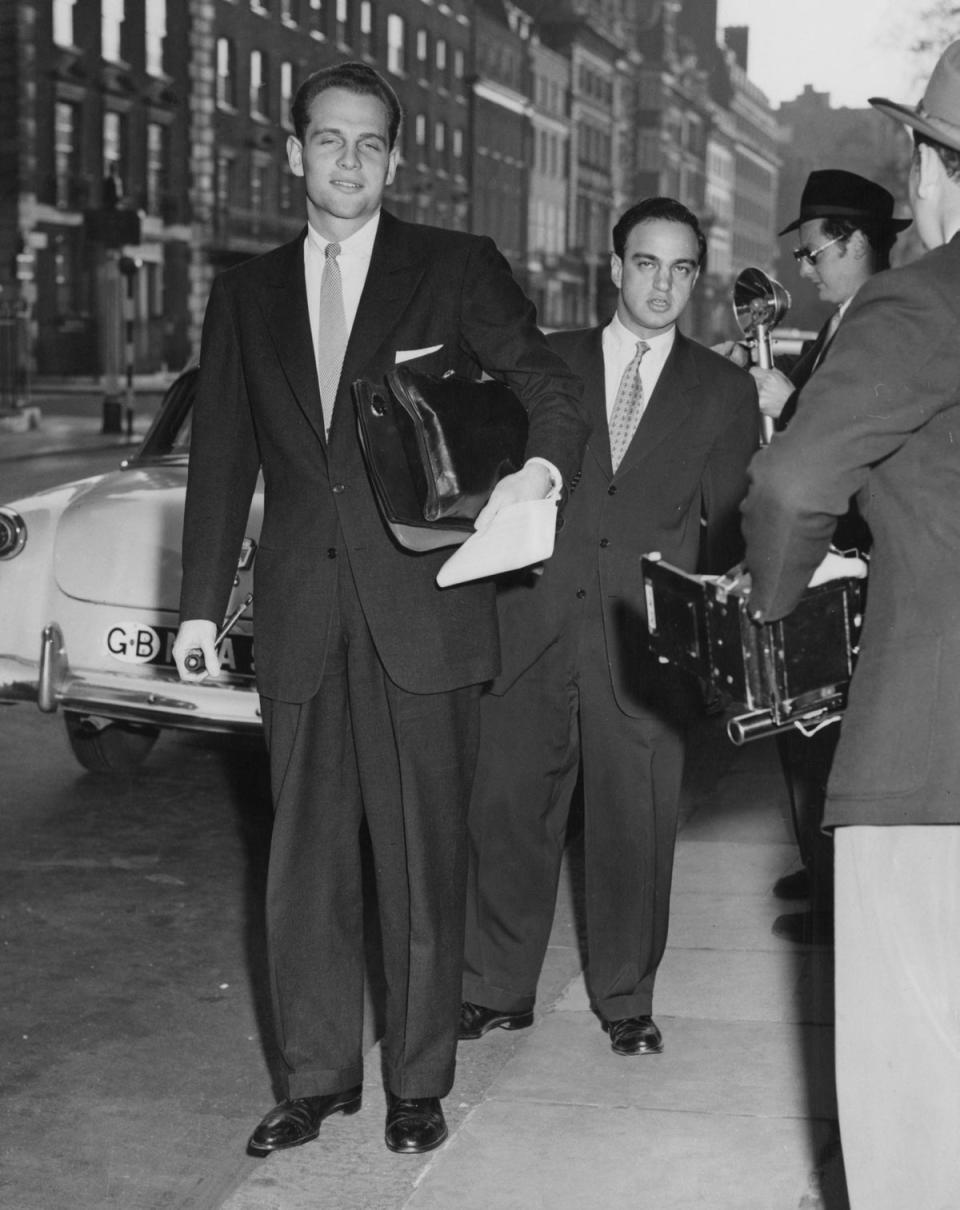

Cohn’s very close friendship with a good-looking heir and unpaid committee consultant, David Schine, fueled not only rumours of homosexuality but allegations of a vendetta against the military because he was attempting to get Schine special Army favours.

“Mr. Cohn, Mr. Schine and Senator McCarthy, all bachelors at the time, were themselves the targets of what some called ‘reverse McCarthyism,’” The Times wrote in its Cohn obituary. “There were snickering suggestions that the three men were homosexuals, and attacks such as that by the playwright Lillian Hellman who called them ‘Bonnie, Bonnie and Clyde.’”

A Studio 54 regular who flaunted flamboyant romances while living “in a closet with neon lights,” as Zion put it, Cohn died from AIDS without ever admitting that he was gay (or suffering from the disease, for that matter.)

“The fact of my controversiality exists and always will,” Cohn wrote years 15 earlier, on the first page of his first book: A Fool For A Client: My Struggle Against the Power of a Public Prosecutor.

Cohn was known to hang around beautiful women but ignore them; he at one point nurtured some type of relationship with Barbara Walters. But he also brought young attractive men along to high-society and political soirees, and regularly threw parties at his Upper East side townhouse and property in Greenwich, Connecticut. “They attract a chorus line of judges, mayors, elected and party officials, monsignors and priests, publishers, gossip columnists, writers, models, actors, landlords, businessmen, celebrities,” reads a 1978 profile of him in Esquire by Ken Auletta. The piece notes that at a party held that spring, Trump (still referred to as a “builder” in the piece) toasted host Cohn.

Tyrnauer, who interviewed relatives and associates of the lawyer for the documentary, pointed to Cohn’s hypocrisy as another major reason for the malevolent reputation.

“He and McCarthy were also going after gay people in the government,” Turnauer told NPR in 2019. “Cohn himself was a closet homosexual, yet he and McCarthy conspired to ruin many gay people’s lives because they were accusing them of disloyalty. And this hypocrisy and this bare-knuckle win-at-all-costs philosophy — which, I will add, he passed on to his great student, Donald Trump — is what caused people to consider Roy Cohn to be an evil person.”

Cohn’s well-heeled and wide-ranging social circle – with clients from the mob to the Catholic archdiocese – all turned a blind eye to his personal life, focusing instead on the lawyer’s formidable and sustained courtroom success. Many of those victories involved beating charges levelled against himself; Cohn was indicted time and time again, and the IRS went after him for decades. After he was charged in 1969 with bribery, extortion, blackmail and conspiracy, Cohn went to trial and delivered his own closing statements after his attorney had a heart attack.

“It tells you something about Roy’s Machiavellian reputation that there are those who believe the heart attack was feigned so Roy could offer his own summation,” Ken Auletta wrote in the 1978 Esquire profile.

“The advantage of defending himself, however, was clear: Since Roy had not been called as a witness in the trial, he was now free to offer his own testimony without being cross-examined. For two days, without a note, Roy delivered an eloquent seven-hour summation, ending with a protestation of love for America. Tears streamed down Roy’s and the jurors’ cheeks.”

He was found not guilty on all counts.

Cohn’s quick-witted eloquence may have never filtered down to his friend Trump, but the two were instead bonded by an anti-establishment love of loopholes, chicanery, favours and gymnastics around the truth – and the legal. When Trump’s organisation was being sued in the 1970s by the federal government for racial discrimination in housing, other lawyers told the future president “You have a good case, but it’s a sticky thing,” Trump told Esquire. Cohn, on the other hand, told him: “Oh, you’ll win hands down!”

Trump also “turned to him with his most important case, the Trump Tower tax abatement, and Roy gave it everything,” Zion wrote near the end of Roy Cohn.

Through it all, however, Cohn’s career was tinged by a sinister bent in the eyes of many.

“If you were in his presence, you were in the presence of evil,” one interviewee says in Where’s My Roy Cohn? – the 2019 documentary which took its name from Trump’s reported utterings bemoaning a lack of an attack-dog attorney.

Decades after his 1978 Esquire piece about Cohn, Auletta called the lawyer “the worst human being I’ve ever profiled.”

Telling a 2022 podcast Cohn was “beyond flawed,” he added: “He was evil in some ways, and yet he was brilliant.”

Cohn’s relentless McCarthyism and ruthless death penalty prosecution of the Rosenbergs forever tainted him in some circles; in others, it was the lawyer’s representation of mobsters, perceived guilty parties or twisting of the truth that made him anathema.

In the end, there were not throngs of friends who remained loyal to Cohn as the lawyer’s star fell. Not only did he contract HIV in the 1980s, but his famed tussles with governmental prosecutions were no longer going in his favour.

“There were other troubles, stemming from legal dealings that many of Mr. Cohn’ s fellow lawyers considered shady,” the New York Times detailed in his obituary. “It was four of these cases that led to his disbarment.’

In one of the cases, a Florida court found that Cohn had tricked a dying multimillionaire into changing his will. When that case and others eventually led to his disbarment, Cohn lashed out, claiming a smear campaign against him.

I like to fight. You might want a nice gentle fight, but once you get in the ring and take a couple of pokes, it gets under your skin.

Roy Cohn

“That kind of combativeness came naturally to Mr. Cohn, who once said: ‘My scare value is high. My area is controversy,’” the obituary quoted him. “‘My tough front is my biggest asset. I don’t write polite letters. I don’t like to plea-bargain. I like to fight. You might want a nice gentle fight, but once you get in the ring and take a couple of pokes, it gets under your skin.’”

Cohn ultimately, however, lost fights on simultaneously crushing fronts. He was disbarred in June 1986 and died just weeks later – from what he maintained until the end was liver cancer.

“It mattered little to Mr. Cohn that he was called ‘a legal executioner’ by Esquire, that the American Lawyer magazine labeled him an ‘an embarrassment’ and that the National Law Journal pronounced him an ‘assault specialist,’” The Times wrote in its August 1986 obituary.

“He shrugged off such criticism … in fact, he seemed to cherish the celebrity that Senator McCarthy maintained even long after his death, and did not mind sharing that limelight,” the Times wrote.

It included Cohn’s response “when asked about his own part in making McCarthyism a household word.

“I sleep well at night,” Cohn told his hometown’s historical paper of record. “I won’t be saying ‘please forgive me’ on my deathbed.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News