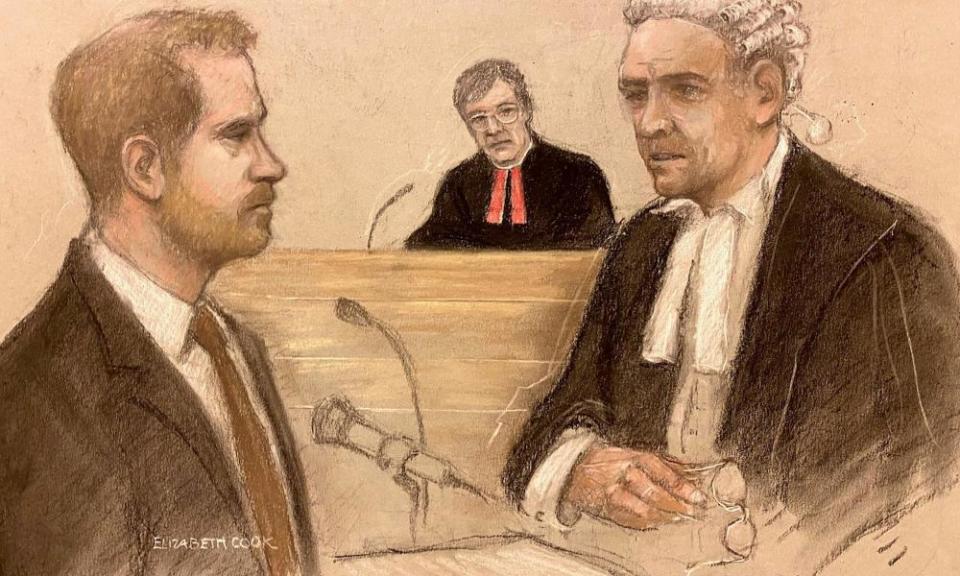

A royal rumble: Prince Harry’s clash in court left him lost for words – but not defeated

Watching Prince Harry in court last week, it was tempting to believe that he had no idea what he had let himself in for. That King Charles’s son had been horribly ill-advised in bringing his phone-hacking case against Mirror Group Newspapers to the King’s Bench and therefore committing himself to an unprecedented day and a half’s cross-examination from a forensic King’s Counsel.

Certainly that was the impression that those newspapers which had most at stake in this case seemed keen to advance. Their reports screamed how the Duke of Sussex “was in the land of total speculation”, that he was “rattled and mumbling … as his case fell apart”, and that “he was not aware of any evidence that he had been hacked”. What could he have been thinking?

One answer to this lay in Harry’s witness statement, released on Wednesday morning, which was a cri de coeur against his lifelong treatment by sections of the press; the mere thought of his and his wife’s nemesis “Piers Morgan [editor of the Mirror for part of the period covered by this case] and his band of journalists earwigging into my mother’s private and sensitive messages (in the same way as they have me) makes me feel physically sick,” he wrote.

In the light of Thursday’s headlines it was hard to miss the statement’s ironies. Looking back on his life, Harry suggested that “it was a downward spiral, whereby the tabloids would constantly try and coax me, a ‘damaged’ young man, into doing something stupid that would make a good story and sell lots of newspapers … such behaviour on their part is utterly vile.” And here he was again, on the front pages, stepping up to play the part of the tabloid “thicko”.

In those reports, a good deal was made of the prince’s admission in court that the case had not even been his idea. He confessed it had come about because of a chance meeting with the so-called “barrister to the stars” David Sherborne. Harry and Meghan, it turned out – from his memoir Spare – had been introduced to the lawyer in 2018 by their friends Elton John and David Furnish while the couples holidayed together in the south of France. Sherborne had suggested to Harry and his wife an “elegant workaround” of the traditional royal veto on using the courts: they could hire him at their personal expense. The implication, in reports, was that what felt like a good idea beside Elton’s swimming pool, looked less appealing in the harsher light of the Royal Courts of Justice.

Several of the papers writing those reports had, a cynic might argue, good reason to cast some shade on the prince and his lawyer. The current case is one of three that Harry is pursuing. Sherborne will also represent him – and Elton John and others – in phone-hacking cases against both Associated Newspapers, parent company of the Daily Mail and The Mail on Sunday, and Rupert Murdoch’s Sun (both of which strongly deny his allegations of illegal newsgathering and argue, with the Mirror Group, that defendants have waited too long to bring their cases). The lawyer – who also acted for Coleen Rooney and Johnny Depp in headline-making cases last year – is easily parodied. He enjoys a year-round tan and luxuriant hair; he sometimes appears more interested in the sonority of his questions than the substance of the answers. But his confidence here is not all misplaced.

It was Sherborne who successfully argued the landmark case, in 2015, that sets some of the context for the current proceedings. That case resulted in total damages of £1.2m paid to eight victims of phone hacking by Mirror Group Newspapers (including Sadie Frost and the Coronation Street actor Shobna Gulati, after whom the “Gulati judgment” is known). That ruling followed an admission and apology by the Mirror Group that “some years ago voicemails left on certain people’s phones were unlawfully accessed”. In his damning 200-page judgment, Mr Justice Mann referred to the “enormity … of what happened” and allowed that a “generic case” could be made of systematic hacking over a period of years in the early 2000s, even though specific call records and other data had been lost or destroyed. Since then the Mirror Group (now Reach) has paid an estimated £100m in out-of-court settlements and associated legal fees to victims of hacking. A further £50m has been set aside. If Harry (and the three other “representative” plaintiffs in this action) are successful, then perhaps a hundred more claimants wait in line.

It is with good reason, then, that the Mirror Group’s counsel, Andrew Green KC, is adamant that Gulati provides no useful precedent and there is “zilch, zero, nil, de nada, niente, nothing” to prove that the hacking of Harry’s phone took place (prior to the trial the defendants accepted and apologised for one instance of illegal information gathering in relation to Prince Harry, but not to phone hacking). In his cross-examination of Dan Evans, the former “designated hacker for the Mirror”, now whistleblower, Green was at pains to emphasise that among scores of acknowledged targets of hacking there had never been a mention of the Duke of Sussex.

With the prince in front of him in court, Green then went painstakingly through the 33 Mirror articles about Harry that were the substance of his case and showed how almost all could have relied not on interception of voicemails or other illegal methods, but on information already in the public domain. Many of the details Harry had found “highly suspicious” could, Green demonstrated, simply have been lifted from earlier reports in the Daily Mail or the News of the World or had come from palace briefings or, in one case, from an 18th birthday interview Harry had given.

The prince was repeatedly made to seem ill prepared and unused to this kind of rigour. Invariably he admitted that he could not remember reading the story in front of him at the time of its publication. “If you hadn’t read it, how did it cause you distress?” Green asked. “They were all distressing to me,” the prince replied.

Watching this performance was to be reminded of the sheer scale of invasive scrutiny that the prince, like his mother, had endured over the years – a kind of national pathology of surveillance. He was right to argue in his witness statement that “journalistic privileges” designed to hold the powerful and criminal to account had been “hijacked” in those years by certain editors, including Morgan, to uncover royal private lives and trivia. (Morgan denies knowledge of hacking.)

It was hardly an exaggeration to suggest, as the Duke of Sussex did in court, that there had been “millions” of stories about him; stories that from childhood informed the world in obsessive detail about his bruised thumb or his broken heart. Though in her evidence on Thursday, the former Mirror royal correspondent Jane Kerr repeatedly refused to accept knowledge of any illegality in the production of these stories, it was not in dispute that it would be the usual practice for her news desk to employ private investigation agencies (including some now known to have been involved in hacking) to help stringers and photographers ambush the young royal on the beach or in the street.

The currency of Mirror “world exclusives” – into which Morgan himself, Kerr said, sometimes inserted the odd sentence – might be a detail of Harry’s tiff with his first love Chelsy Davy, or a poker night with his mates, or the frequency of phone calls from his army postings (details supplied by “royal sources” or “pals”). The “public interest” justification for many of these stories rested on that unspoken pact between tabloids and monarchy, that meant the nonsense of the hereditary principle and the palaces went unquestioned as long as the bullying invasions of privacy were tolerated.

Harry (address him as “your royal highness” on introduction, Sherborne suggested to the court, embarrassingly, and then plain old “Prince Harry” after that) had very long ago reached the point of “paranoia and depression” about that compact. Asked by his barrister how it felt to go through these articles again, particularly those about his mother and his doomed relationships, Harry appeared genuinely choked up and lost for words: “It’s a lot”, he eventually said, and nobody could disagree.

In this final questioning it seemed striking, nonetheless, that Sherborne was keener to ask the prince about feelings than about facts. In the light of the Gulati ruling, however, the comparative absence of the latter (“not one item” of evidence of phone hacking, Green said) may not be the fatal flaw in Harry’s case that some observers assume. Sherborne referred frequently to the alleged “mass deletion” of emails and other evidence that may have had a bearing on this case. Earlier in proceedings, Graham Johnson, a former Sunday Mirror investigations editor, who received a suspended sentence for phone hacking in 2014, told the court that hundreds of people at Mirror Group Newspapers had been involved in a cover-up of illegal behaviour. “I investigated drug gangs in Liverpool, fraud factories in south-east London, and street gangs in Birmingham,” he said. “The Mirror Group is no different from an organised crime group in that respect. This is a true crime story.”

In cross-examination, Green suggested that Johnson was a “convincing faker”, and had “utterly, utterly embellished” his accounts.

Still, sitting in court, watching the fifth-in-line to the throne floundering, you found yourself occasionally wondering this: was it really plausible that an organisation that had previously been found to have hacked into, say, Alan Yentob’s voice mails twice a day over a period of years, never once employed the same methods against “Hooray Harry” or his small circle of intimates?

That may yet be the question that also gives Mr Justice Fancourt pause.

The case continues.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News