The rush to create the ‘iPhone of AI’ has begun

The Consumer Electronics Show is supposed to be a glimpse at the future. So, of course, this year’s event – held this month in Las Vegas – was saturated with artificial intelligence, or things claiming to be it. AI was put into every day household items and furnishings: there was AI mirrors, AI mattresses and AI washing machines. There were cars with ChatGPT and there were robots with wheels so that they can drive around people’s houses.

But the most discussed product of the event was not artificial intelligence stuck into an existing product, like so many of the other marketing plays on display. Instead, it was an entirely new product built solely for AI.

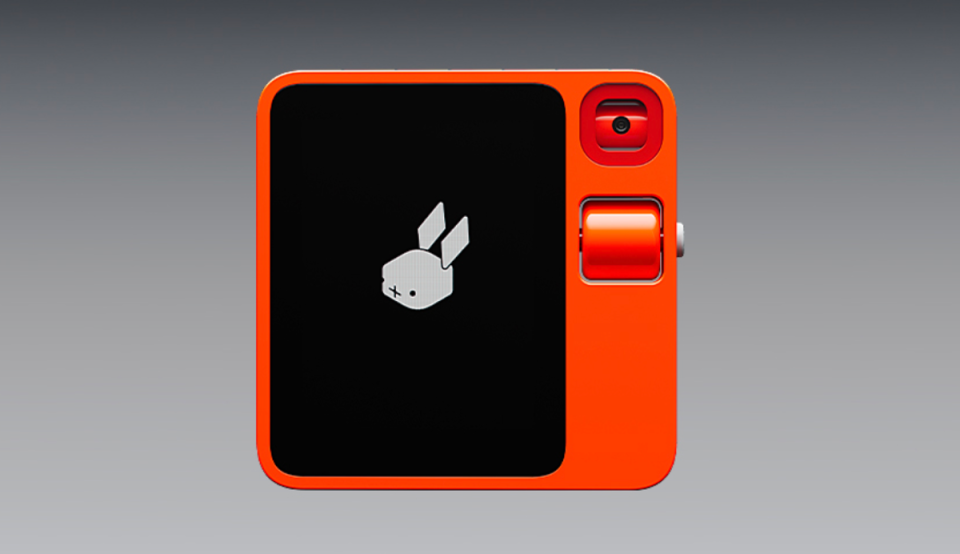

It was the Rabbit R1, and beyond that it’s not quite clear what it is. It looks like a rounded rectangle with a screen, a camera and a scroll wheel to let you get around. It doesn’t really look like a phone, but that is probably the closest comparison. Its creators describe it as the “future of human-machine interface”, and a “pocket companion”.

Rabbit’s R1, however, doesn’t want to be a phone – if anything, it wants to replace it, eventually. The idea is that it will bring different apps together in one interface, controlled by artificial intelligence. It was trained by watching people use different apps: seeing how people choose a song on Spotify, or order an Uber, for instance. Once it has watched that enough then it is, theoretically, able to do it for itself – so that you can just ask for a taxi and have it arrive.

The R1 is just one of a range of new hardware devoted to artificial intelligence. The uniting idea behind them is that AI is not just only another technology that can be accessed through our phone, but potentially a whole new way of interacting with technology. What’s more, they might get rid of the phone entirely, or at least force us to use them less.

That is exactly the idea behind the ‘AI Pin’, a tiny computer made by the previously mysterious company Humane. Humane had been working in secret since it was founded in 2019, but broke its cover late last year to reveal its big plan: effectively a smart brooch that works as a portal to AI.

It clips onto your lapel and aims to do the work of your phone without forcing you to look at its screen. A built-in camera means that you can just ask it to capture a moment, for instance; if you want to know who the current prime minister of Denmark is then you can just ask the built-in ChatGPT rather than tapping away with your fingers.

But as soon as it was released, the AI Pin instantly received mockery. Its launch video was awkward, stilted and included the pin making a basic mistake as it tried to answer a question. Soon after, as the hype around the R1 was building, Humane laid off ten people or four per cent of its employees, with the company describing it as cost cutting measures, according to The Verge.

The reaction to the R1 has been wildly different. The $199 device immediately sold out and has released four more batches since, all of which have also sold out. It’s not clear exactly why the R1 has done so much better than the AI Pin: it might be that the product is a little more fun, and its promoters a little less self-serious; it might be because it aims to be a fun glimpse of the future rather than the bright beacon of progress.

It might also be that people are not quite sold on Humane’s vision of getting rid of phones. It has become the basic assumption in technology that everyone feels a kind of magnetic resentment towards their phone: unable to tear themselves away, but hating themselves as they do so. That sentiment seems to have guided the AI Pin, at least in its marketing.

Tech companies are clearly aware of the increasing concern over the questionable effects of spending too much time looking down at our devices. Everyone from Apple to Meta has over recent years introduced “digital wellbeing” tools, intended to help people be more mindful about how they spend time with their devices. It’s not clear of course whether they too were responding to actual sentiment or just the sense that everyone else is worried about their devices, but it was a clear recognition that people at least consider there to be a problem.

In some cases, the people apparently trying to free us from our phones were actually responsible for them in the first place. Imran Chaudhri, the chief executive of Humane, spent more than 20 years at Apple, and is credited with some of the central parts of the iPhone’s design.

But Chaudhri might have done too good a job in the first place. It may not be true that people want to give up their phones – after all, the iPhone still sells in vast numbers. Apple and other phone manufacturers are racing to integrate artificial intelligence into their devices, and it might be that the glass rectangle remains the best way of interfacing with technology, even if the technology itself changes. (And if people want to avoid looking at their phone then they can just speak to their AirPods – which Chaudhri also worked on.)

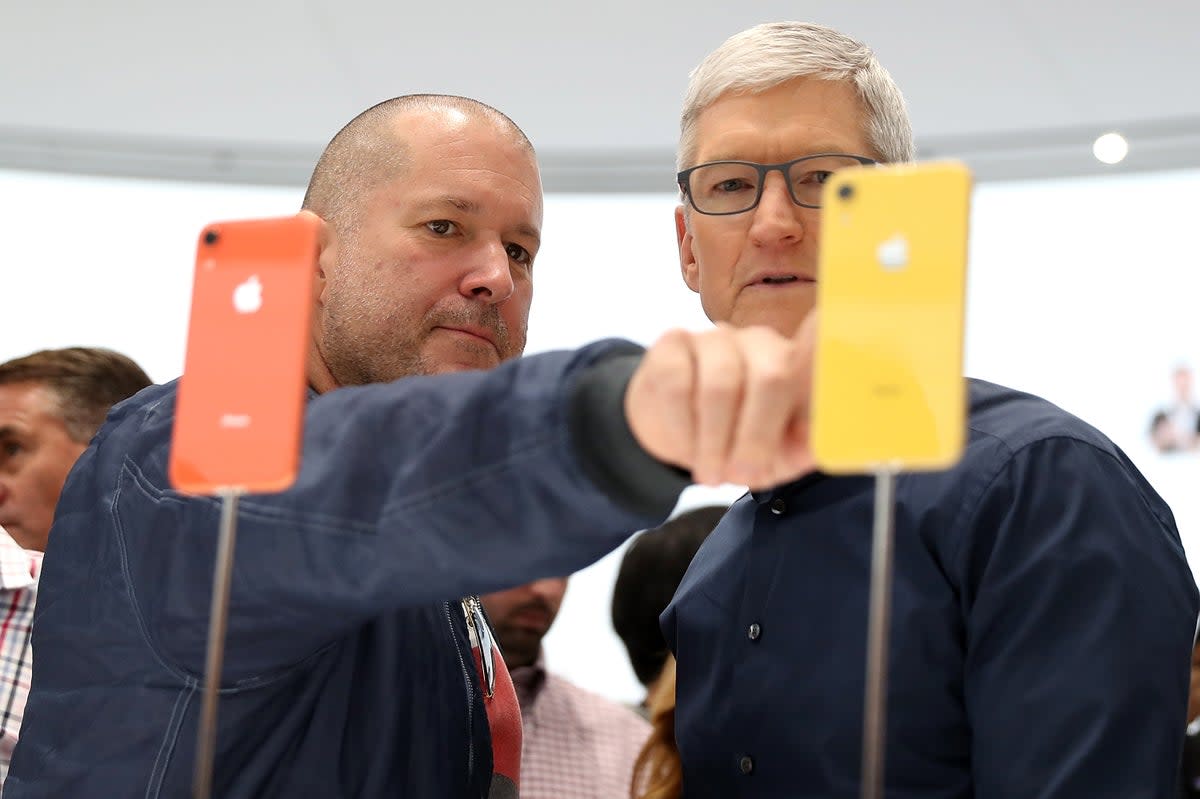

There are rumours of yet more devices to come. Towards the end of last year, it was reported that ChatGPT creator OpenAI had been working with former Apple design chief Jony Ive, with the plan of building the “iPhone of artificial intelligence”. It is another product oriented mainly around the hardware: the aim of to allow for a more natural user experience when using AI, according to The Information, which first reported the plans.

Once again, that has big backing: reports indicate that it has been funded by Softbank chief executive Masayoshi Son, who has spent more than a billion dollars on the effort. But once again it could be beaten by one of its designers’ previous successes: why can’t the iPhone be the iPhone of artificial intelligence?

Yahoo News

Yahoo News