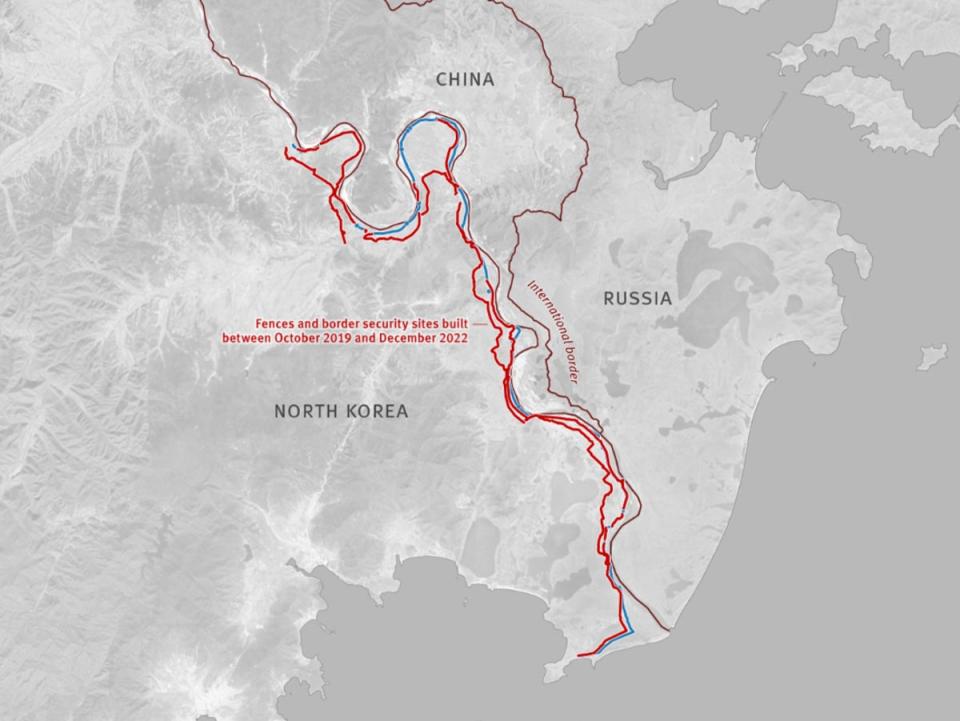

Satellite images show how North Korea has transformed its border with China

Since the start of the Covid pandemic, North Korea has systematically sealed the country’s borders using “expanded fences, guard posts, strict enforcement, and new rules, including a standing order for border guards to shoot on sight”, a new report from Human Rights Watch has revealed.

Analysis of the satellite images of hundreds of square kilometres of North Korea’s northern border shows how key trade and crossing points were fortified after the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic began. The satellite images also show the level of security infrastructure before and after 2020 on the border and “the scale, efforts, and resources that the North Korean government has invested in fortifying the border through new fencing, infrastructure, and its increased deployment of security personnel”.

The HRW report titled, “A Sense of Terror, Stronger than a Bullet: The Closing of North Korea 2018–2023” was released on 7 March and shows how between 2017 and 2023, the already isolated country effectively closed off North Korea from the rest of the world and “stopped almost all cross-border movement of people, formal and informal commercial trade, and humanitarian aid”.

In its analysis of the satellite images, HRW concluded that between 2020 and 2023 North Korea built a total 482 kilometres of new fencing in the areas and enhanced another 260 kilometres of primary fencing that had existed before.

Satellite images from April 2023 showed some fencing still under construction, it added.

Captured between 2019 and 2023 and spanning approximately a quarter of its northern border, the images also reveal the construction of new guard posts and the establishment of buffer zones.

The report adds: “Ostensibly to address the Covid-19 pandemic, North Korean authorities instituted strict border and regional lockdowns, issued a shoot-on-sight order to guards—still in effect in January 2024—for any person or wild animal approaching the northern border, fortified or built new border fences and security facilities”. It states that the country “imposed strict limitations on foreign trade and domestic travel and distribution of food and essential products… and implemented excessive and abusive restrictions on freedom of movement and quarantine measures.”

Human Rights Watch identified 6,820 border security installations along the 321 kilometres of the border that were analysed, and that encompassed guard posts, watchtowers, and garrisons.

“The overall number of border security facilities in the areas analysed increased 20-fold since 2019. There was a massive increase in the number of guard posts, which mushroomed from 38 before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, to 6,506,” the report noted.

The report highlighted the devastating consequences for the North Korean people of the government’s worsening isolation from 2019 until late 2023.

One of the cities that the report covered was Hyesan, which serves as the main gateway to and from the Mount Paektu and Samjiyon tourist areas. HRW analysis showed the area has seen significant redevelopment efforts since Kim Jong-un designated their transformation a national focus in 2013.

Interviews with over 30 North Koreans who have ties to Hyesan city and fled the country post-2011 reveal a common sentiment: it’s rare to find a family in Hyesan without at least one member who has defected to South Korea.

North Korea has a standing order for border guards to “shoot on sight” anyone approaching the border w/out permission. The govt’s expanded border security has made almost all unsanctioned travel impossible, including to escape the country. New @HRW report. https://t.co/hSv8UtGLtl

— Bill Frelick (@BillFrelick) March 7, 2024

P Su Ryun, a former merchant in her forties with a wide network within Hyesan said: “There are no honest people left in Hyesan city.” She explained that everyone she knew there had at some point engaged in activities deemed illegal by North Korean authorities: unauthorised trade, consuming forbidden information or media, communicating with people outside North Korea, and watching South Korean films and TV shows.

L Young Mi, a former herbal medicine trader in her 30s from Ryanggang province who now lives overseas, said a relative in North Korea told her in November 2022 that nobody could get close to the border: “My [relative] said there were no words to describe how hard life was. There was no [informal] trade with China, not even to get some rice or a bag of wheat. If [authorities] heard of a soldier allowing that, that person would just disappear ... Soldiers are very scared… My [relative] said people in [her area] said there is not even an ant crossing the border.”

The report also states that in August 2020, the authorities issued a shoot-on-sight order on the northern border and set up a “buffer zone” and there was a nighttime curfew imposed from 8pm to 5am from April to September that year and from 6pm to 7am from October to March.

“Media and an activist with contacts inside the country said this curfew remained in place in many areas long after Kim Jong-un’s declaration of ‘victory’ over Covid-19 in August 2022, and the buffer zone was still in place in the northern border area as of January 2024.”

HRW notes that “very few North Koreans have been able to escape the country since 2020”. In 2021, 2022, and 2023, only 63, 67, and 196 North Korean escapees arrived in South Korea — a significant decrease from the 229 arrivals in 2020, the 1,047 arrivals in 2019, and the 2,706 in 2011.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News