Scientists have built a ‘digital twin’ of Earth to predict the future of climate change

Scientists have built a highly accurate digital simulation of planet Earth to provide reliable information about extreme weather and climate change.

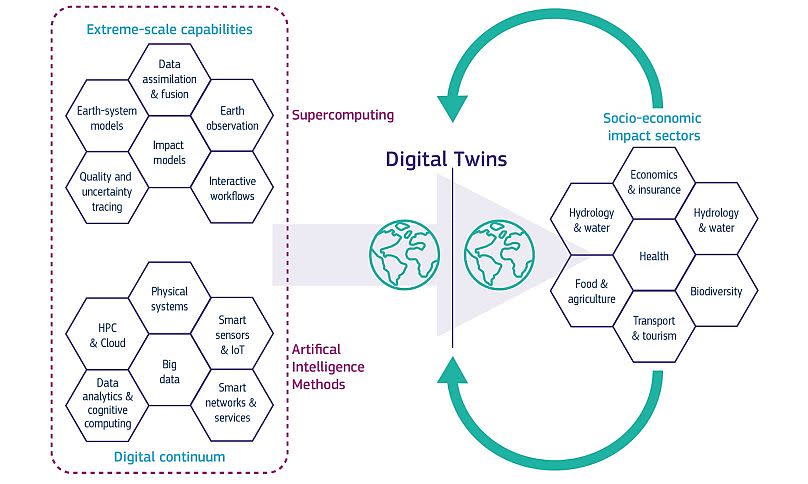

This AI-powered “digital twin” virtually simulates the interaction between natural phenomena and human activities to predict their effect on things like water, food and energy systems.

In the past, climate and weather predictions have either focused on local regions or larger global systems. The new project, known as Destination Earth (DestinE), brings all of this information together alongside human actions to “depict the complex processes of the entire Earth system”.

The project, activated by the European Commission on 10 June with over €315 million in funding from the Digital Europe programme, hopes to provide a method of testing scenarios that will help policymakers and scientists to prepare for the future.

"The launch of the initial Destination Earth (DestinE) is a true game changer in our fight against climate change," says Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice-President for a Europe Fit for the Digital Age. "It means that we can observe environmental challenges which can help us predict future scenarios - like we have never done before... Today, the future is literally at our fingertips."

DestinE currently consists of two models - one focusing on climate change adaptation and the other on weather-induced extremes - which draw on data from sources like Copernicus.

It is expected to continually evolve over the coming years, completing a full digital replica of the Earth by 2030.

Why do we need a 'digital twin' of Earth?

With our weather becoming more severe, there is a growing need to estimate the impacts of the climate crisis. Over two million people died in extreme weather-related events between 1970 and 2021, according to the WMO.

Extreme heatwaves in 2003 and 2010 accounted for 80 per cent of weather-related deaths in Europe during this period - and climate disasters are getting worse, with May breaking the global temperature record for the 12th month in a row.

DestinE will be used to help Europe respond to natural disasters more effectively, adapt to climate change, and assess the potential socioeconomic and policy impacts of such events.

Hypothetical scenarios such as building wind farms across Europe and information on where to plant crops as our climate changes could be provided by the model.

“If you are planning a two-metre high dike in The Netherlands, for example, I can run through the data in my digital twin and check whether the dike will in all likelihood still protect against expected extreme events in 2050,” said Peter Bauer, co-initiator of Project Destination Earth, when the project was initially announced in 2021.

‘Without farmers, Sicily as we know would not exist’: Drought takes its toll on crops and livestock

What went wrong for the EU election-losing Greens and Liberals?

How will a ‘digital twin’ help Europe reach its climate targets?

For Destination Earth, the European Commission has partnered with the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), the European Space Agency (ESA) and the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT).

The European Union is making a big investment in green technology as part of the bloc’s plan to become the first climate neutral continent by 2050. The EU hopes this project will enable more sustainable development and support environmental policies in the coming years.

Supercomputers used to power the simulation

But the climate impact of the simulation itself could be significant. In a 2021 study, researchers estimated that they would need a supercomputer with 20,000 graphics processors consuming around 20MW of power to create the highly complex model.

DestinE relies on Europe's High-performance computers (EuroHPC), including the LUMI supercomputer in Kajaani, Finland.

Although it is unclear how the system will be powered, computing experts previously stressed the importance of carbon-neutral energy in its development. Finland gains almost half of its energy from renewable sources, coming second only to Sweden in the EU.

By 2027, the team aims to have additional digital twins and services up and running. The data from these simulations will then be combined to create “a full digital twin of Earth” by the end of the decade.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News