Sea crossings, cleaning, and Connery’s coffee: memories of Galicians who came to Britain

The tens of thousands of Galicians who left north-west Spain to migrate to the UK between the mid-1950s and early 1970s, swapping poverty and the straitjacket of the Franco dictatorship for a strange, liberating and often unfathomable new home, endured shock after shock.

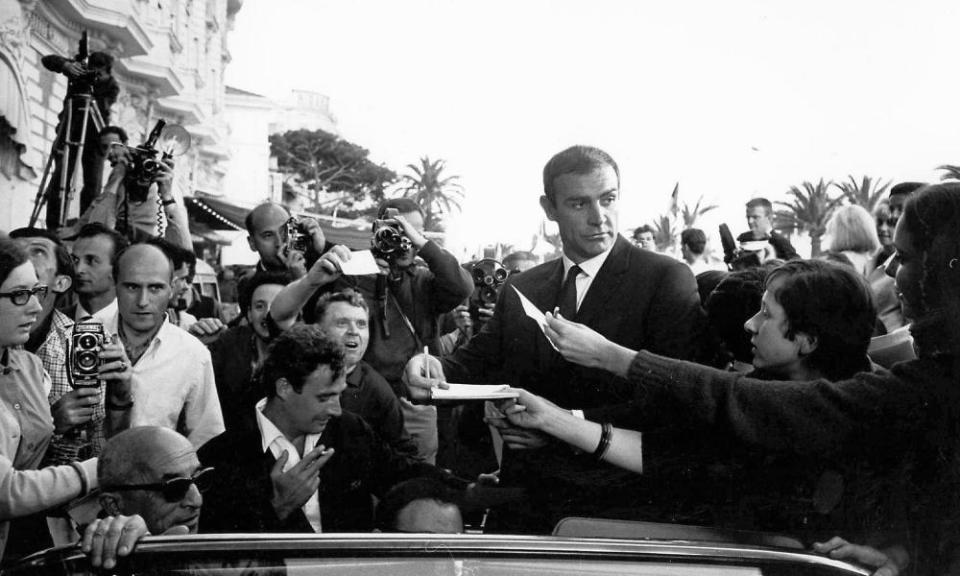

For some, it was the mysterious sprawl of the London tube network; for others, the equally labyrinthine and bewildering British class system. Then there was the lack of the turnip tops so necessary for making a familiar vat of caldo. For the late Amalia López, however, it was forever having to say no to a cup of Sean Connery’s undrinkable black coffee.

Like many of the migrant gallegos, López, who died last year, found work in London as a domestic cleaner – albeit one whose clients included Connery and Terence Conran.

“I grew up hearing all these wonderful stories about Sean Connery’s flat and how he always offered to make Amalia a coffee when she went to clean,” says Xesús Fraga, a Galician writer who is the curator of a new exhibition that commemorates and celebrates a half-forgotten migration.

“She’d always say: ‘No, no, Mr Connery, please don’t bother.’ I once asked her why she refused. ‘Because he didn’t know how to make a damn coffee!’ she said. ‘It was horrible and really black!’ Sean Connery used to laugh and say: ‘Oh, Amalia, not many women say no when I offer them a coffee.’”

Fraga’s exhibition, As xeracións do Montserrat (“the Montserrat generations”) – named in honour of the passenger ship Montserrat, which, with its sister ship the Begoña, brought Galicians to the UK – is a deeply personal undertaking. The award-winning author, journalist and translator was born in London in 1971 to a family that had swapped their Galician home town of Betanzos for the British capital.

His grandmother Virtudes struck out for London in 1961 to earn money to support her three daughters, whom she had to leave behind. Her husband, a dreamer who had headed to Venezuela six years earlier in pursuit of an oil fortune he would never find, had failed to reply to a final plea to come back to the family.

Like her friend Amalia, whose shifts she covered, Virtudes found work as a cleaner – work that would prove vital in supporting her family. Having come from a family of subsistence smallholders, she knew no English and nothing of the country besides its reputation under Francoism “as kind of an evil place” that was too Anglican and too liberal.

When Fraga’s mother, Isabel, then 18, made the crossing two years after her mother, she came with a friend who had taken the precaution of having a local priest bless and protect her purity “so that her body and her soul wouldn’t be corrupted in that dangerous Babylon that was London at the time”.

As Fraga points out, the migration to the UK was led by women because the jobs on offer there were mainly cooking, cleaning and care. In countries such as Germany, Switzerland and France, which attracted more men, the jobs were in factories and manual labour.

“Migration to the UK gave these women a degree of independence and control over their lives that they would never have had in Franco’s Spain, where a woman couldn’t have a passport or a bank account without their husband’s permission,” he says. “They had to fake my grandfather’s signature so my grandmother could go to the UK.”

Despite being starved and ill-treated by the first family she worked for, Virtudes – who came to be known by her English friends as Betty – stayed and flourished. Unlike many of her fellow migrant workers, who only worked as long as it took them to save up to buy a house or flat at home, she remained in the UK for three decades. Isabel, who first lived in England from 1963 to 1967, returned for another stint with her husband, Antonio, from 1970 to 1976.

A photograph showing Virtudes and Isabel on the deck of the Montserrat in 1963 is one of the many items featured in the exhibition at the Kiosco Alfonso in the Galician city of A Coruña.

Others include the typewriter Isabel bought in London – and on which her son would write his school essays and first stories – and the first pound note another woman earned. Even more poignant is the camera a young couple bought so they could take pictures of the baby daughter they left behind and only saw for a month each year.

Other exhibits – such as the English and Spanish versions of Agatha Christie’s Three Act Tragedy that an enterprising young gallego read simultaneously to teach himself his new tongue – reveal the lengths to which the newcomers went to educate themselves.

Fraga, the little Londoner who returned to Galicia with his parents and his Paddington Bear books when he was five, remains a child of two cultures. The boy whose peanut sandwiches blew the minds of his schoolmates as they unwrapped their bocadillos de chorizo has grown into a man who still supports Queens Park Rangers but who, like any good denizen of Betanzos, loathes onion in his tortilla de patatas.

Although his father eventually found a place in Fulham where he could buy turnip tops, Fraga’s family, like many others, came to suffer from a reverse nostalgia when they resettled in Galicia.

“When these people came back, they’d miss things like PG Tips or Sunday roasts, because they’d got used to things in the UK and grown fond of them,” he says. “Mine must have been the only family cooking curries in the 1980s in Galicia because my dad used to cook them.”

Two years ago, Fraga’s memoir, Virtudes (e misterios) – “Virtues and Mysteries” – won Spain’s national narrative prize and he hopes it might one day find an English publisher. Julian Barnes, two of whose novels Fraga has translated into Galician, describes the book as a “window on to a little-known immigration to London: that of Galician ‘guest-workers’ who came here over several generations … [and] moved among us without our noticing”.

Fraga’s own family history certainly borders on the novelistic. In 2000, one of his aunts finally tracked down his grandfather, Virtudes’s husband, in Venezuela, and he came home to live with his wife after almost half a century of separation. “And when I say they lived together, they shared the same bed. It was like: ‘There’s been a 45-year parenthesis, now let’s resume our lives.’”

But, as he points out, all those Galicians have their own tales to tell: that is the idea of the exhibition.

“People are sometimes quite dismissive of migrants’ stories,” he says. “And I’ve met a few people along the way who don’t like to talk about migration because it reminds them of when we were a poor country. It’s like we want to hide that bit of our history. And I think that’s wrong – mainly because people keep migrating from here and we also receive migrants. I’ve got friends in Betanzos from Venezuela, Cameroon and Senegal.”

The show is also a belated attempt to repay the huge debt he owes his grandmother and his parents.

“My family farmed the land and had to pay the landowners in wheat and corn,” he says. “I was the first person in my family to go to university and I’m fully aware of the fact that I’m in debt to their sacrifice and to their vision.”

• As xeracións do Montserrat is at the Kiosco Alfonso in A Coruña until 14 January

Yahoo News

Yahoo News