Geomagnetic storm severe enough to bring northern lights to California?

A severe geomagnetic storm is impacting Earth and could produce powerful northern lights displays across portions of the United States on Sunday and Monday, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said.

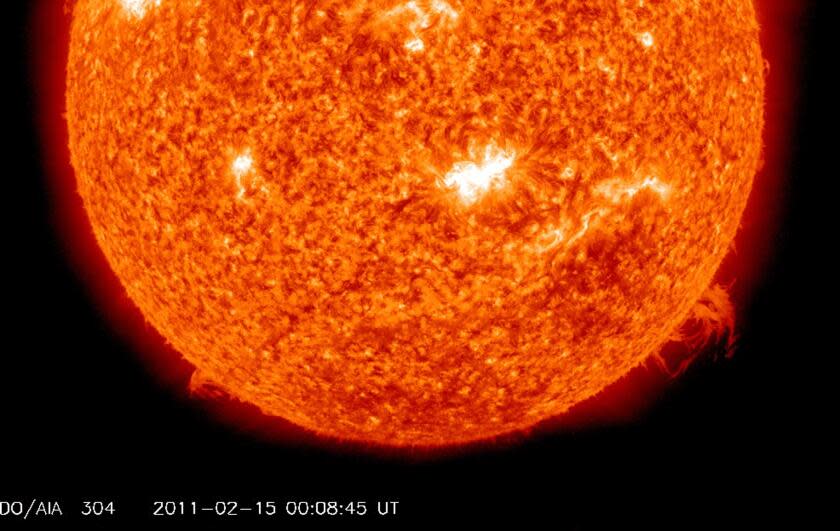

The agency's Space Weather Prediction Center first issued a geomagnetic storm watch Saturday, warning that a coronal mass ejection — an explosion of plasma and magnetic material from the sun — was making its way toward Earth.

On Sunday afternoon, the agency upgraded the storm's strength to G4, or "severe," indicating a major disturbance in Earth's magnetic field. The storm is expected to remain at a "strong" G3 level or higher through at least Sunday evening.

"The public should not anticipate any adverse impacts and no action is necessary," the SWPC said.

However, geomagnetic storms can have effects on technology, including increased and more frequent voltage control problems and higher chances of anomalies or effects on satellite operations. The center has notified infrastructure operators — including those of power grids and satellite and communications agencies — to prepare for possible effects, according to Bill Murtagh, program coordinator with the SWPC.

“If they don't take action, we can have some significant problems with our satellites, our communication systems, our navigation systems, our electric power supply,” he said.

The 23 March CME arrived at around 24/1411 UTC. Severe (G4) geomagnetic storming has been observed and is expected to continue through the remainder of the 24 March-UTC day and into the first half of 25 March. pic.twitter.com/CDXQtyv4yp

— NOAA Space Weather (@NWSSWPC) March 24, 2024

Personal items such as cellphones and GPS tools tend not to be affected. The geomagnetic currents disturb the power grid, not electronic devices, he said.

He noted that a strong geomagnetic storm in 1989 knocked out power to much of the Canadian province of Quebec.

“It's happened before," Murtagh said, "and our big concern is if we get a big enough storm, it could occur right down here in the lower 48."

This is the third geomagnetic storm to reach G4 status during the current 11-year solar cycle, which began in 2019, according to Murtagh.

"The eruption occurred on the sun on Friday evening," Murtaugh said, "and it pumped out this big coronal mass ejection, which made its way along the 93-million-mile transit from sun to Earth in just over 37 hours — which is actually quite fast, probably the fastest this solar cycle."

The two previous G4 storms this cycle occurred in March and April 2023.

Geomagnetic storms are known for creating the dazzling visual displays auroras, also called the northern lights when they appear in the Northern Hemisphere.

Auroras are formed by interactions between the sun's solar wind and the Earth's protective magnetic field. They become brighter and more active as geomagnetic activity increases — and become visible farther from the poles.

The SWPC's latest aurora forecast favors a strong display over Alaska and Canada on Sunday and Monday nights, as well as potential visibility across Washington, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, Minnesota, Michigan and Wisconsin. Visibility may expand as far south as Oregon, Wyoming, Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois and New York, the forecast shows.

Read more: Some Californians saw a rare display of the northern lights. Here's why it happened

Although California does not appear to be in line for the show, that could change, Murtagh said. He noted that a similarly strong storm last March did deliver northern lights to portions of Northern California.

"The solar wind speed is still high, the magnetic field is still strong, and it's just the way it's oriented," Murtagh said. "We just cannot predict if or when that will shift more to a southerly direction."

If the storm does shift and begin to bring in more energy, it could generate lights visible in Northern California, he said, adding, "We haven't ruled it out."

Even if Sunday's show doesn't make it to the Golden State, there should be more chances in the next three or four years as the solar cycle peaks. The odds also tend to increase around equinoxes — the vernal equinox occurred last week — due to a more favorable tilt in the Earth's axis, Murtagh said.

"We're in that favorable time right now — it's solar maximum, we are seeing these eruptions, and we'll see plenty more of them in the next several years before we start winding down by 2029 or 2030."

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News