‘She’s badass’: how brick-throwing suffragette Ethel Smyth composed an opera to shake up Britain

She was bisexual, served a prison sentence and was so outraged by cuts to her opera The Wreckers that she stormed the orchestra pit. Finally, this summer, it will be heard as its extraordinary composer intended

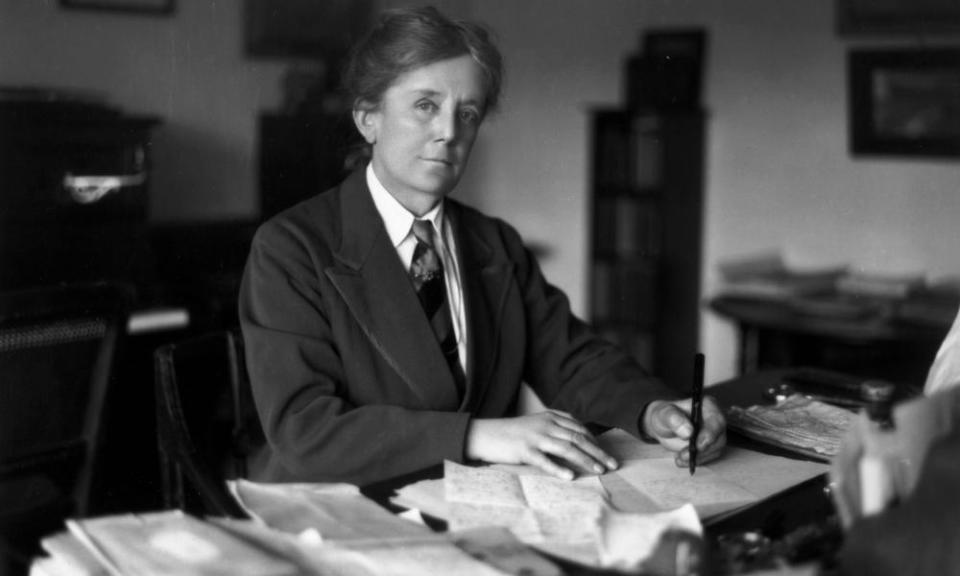

‘She was a stubborn, indomitable, unconquerable creature. Nothing could tame her, nothing could daunt her,” said conductor Thomas Beecham, speaking in 1958 about the composer Ethel Smyth. “She is of the race of pioneers, of path-makers,” agreed her friend Virginia Woolf. “She has gone before and felled trees and blasted rocks and built bridges and thus made a way for those who come after her.”

“She’s badass. I’d love to have met her,” says Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts. The tenor sings in a new production of Smyth’s 1906 opera The Wreckers, which makes its debut at Glyndebourne on 21 May, and will be performed at the Proms this summer. Her music is “incredible”, the conductor Robin Ticciati says. “She uses the brass and the timps as weapons, blades!”

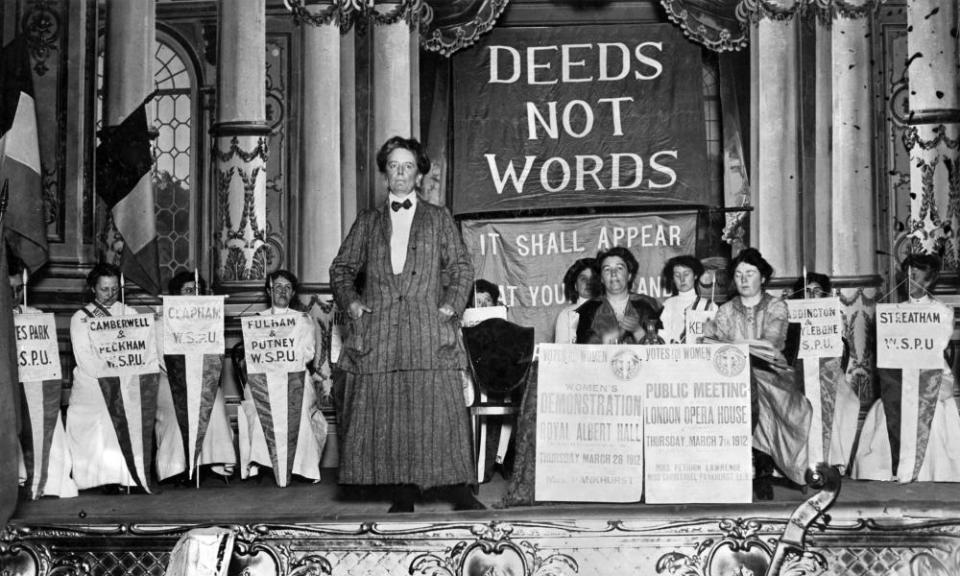

Smyth wrote six operas, a mass, countless chamber works and even a ballet, but she is best known today for her 1910 song The March of the Women, which became the official anthem of the suffragette movement. She was a passionate activist, throwing bricks through the windows of the homes of cabinet ministers – which led to a two-month jail sentence. Beecham recalled visiting her in Holloway prison: “On this particular occasion, the warden said: ‘Come into the quadrangle.’ There were a dozen ladies, marching up and down, singing hard. He pointed up to a window where Ethel was leaning out, conducting with a toothbrush, also with immense vigour and joining in the chorus of her own song The March of the Women.”

The Wreckers is set in a remote corner of 18th-century Cornwall where villagers live a precarious existence plundering ships lured on to the rocks, and invoking ancient salvage rights that allow them to murder shipwrecked crew for profit. But when two of the community resist this and the strictures of their own roles, tragedy ensues.

She subverts operatic tropes. She made the moral heart of the opera a mezzo – normally consigned to witches, bitches or breeches roles, and the soprano is outspoken and feisty

Lauren Fagan sings the role of Avis, one of the two central female characters. “She’s a really awesome and exciting person to sing,” Fagan says. “She makes bold decisions. I’m feeling quite empowered and strong, even if at the end Avis too is cast out of the community.”

For the director, Melly Still, the work reflects the defiant, unorthodox views of its creator. “Librettist Henry Brewster and Smyth were clear that they weren’t making this a piece about the Cornish people and wrecking specifically,” Still says. “For them it was a symbol of Britain and its insularity.”

Little about Smyth was ordinary, from her bisexuality to her determination to compose on her terms, and refusal to accept that her voice was any less important than that of her male counterparts. “I would certainly call The Wreckers a feminist opera,” Still says. “It’s about the women in it finding their voice. Its central character, Thurza, tries to break free from the restricted world she is forced to live in. And Smyth subverts all the operatic tropes. She made the moral heart of the opera a mezzo, a voice type normally consigned to the witches/bitches/breeches roles; and the soprano, Avis, is a really feisty character – not the classic transgressor saved by a prince charming.”

As much as it’s about defiance and individual freedoms, Ticciati adds, the opera is about how a community turns into a mob. With its dark narrative of scapegoats and violence and its remote coastal setting, the work has parallels with Benjamin Britten’s opera Peter Grimes, although Britten said he did not know Smyth’s work. It’s hard to imagine he didn’t come across bits of it at the Proms: in the 35 years between 1913 and 1947, 27 separate Prom seasons featured either The Wreckers’ Overture or its Prelude to act 2. Productions and complete recordings, however, were few and far betweeneven during Smyth’s lifetime, and Glyndebourne’s staging is the first professional one done in French, the language in which the opera was originally written.

The history of Smyth’s opera is as dramatic as the Cornish coast where it is set. Smyth’s librettist, Brewster (her lover and lifelong friend), was a bilingual French/English speakers. Smyth, who studied in Leipzig, was steeped in European musical traditions and spoke German and French fluently. Their decision to write the libretto in French is likely to have been a pragmatic one. “The conductor at the time at Covent Garden was the French-born André Messager. Perhaps she thought ‘a French conductor is bound to put this on,’” Still says. Smyth also hoped that a French-language opera would find a more receptive audience over the Channel where she felt there wasn’t the same divide between “composers” and “female composers”. She was, however, wrong on both counts, and it was in German, not French or even English, that the Wreckers was premiered, in Leipzig in 1906.

The performance was well received, but Smyth was horrified by cuts made to the third act and, when the conductor refused to reinstate the missing passages, she marched into the orchestra pit herself and removed the musicians’ parts and the full score, and took them on a train to Prague. An under-rehearsed performance there was a disaster and although her work had found a fan in Gustav Mahler, his hopes to put her opera on in Vienna in 1907 came to nothing.

Back in England the indomitable Smyth persuaded Beecham to listen to her work, as he recollected. “She came to me in a very excited state. She said, ‘You have got to conduct my opera The Wreckers … Will you come and see me, and I will go through it with you?’ She played the whole piece through, mostly the wrong notes, but with a vigour and elan that was really very inspiriting.”

And so 1909 saw six performances at Her Majesty’s theatre, and then, the following year, at Covent Garden – the first opera by a woman to be produced there. “Smyth and a poet friend of hers translated the French into a very kind of baroque Edwardian ladies’ poetry, and there were cuts to shorten the work. But as soon as you start cutting, the character and all the complexity vanishes and it all becomes quite two-dimensional,” Still says.

Even so, Smyth’s opera was a success – even King Edward VII came to see it – but then her work all but disappeared from opera houses. A semi-staging at the Proms in 1994 brought her back to the Royal Albert Hall, and in 2006 Cornwall’s Duchy Opera staged a reduced and newly translated English version of The Wreckers in its centenary year.

At the same time as thinking: ‘What did Ethel want?’, we’ve also been asking ourselves: ‘What can we do to make this piece live at its best?’

Conductor Robin Ticciati

The opera has however, never been performed as Smyth originally wrote it. “We wanted to go right back to the source” says Ticciati.

“Opera in its original language flows better,” says James Rutherford, singing Laurent. “The minute you change something there’s always a compromise. Going back to the original makes you think: ‘OK, this is obviously what was intended.’”

“We’re all still waiting to hear what it sounds like,” l Ticciati. The London Philharmonic Orchestra are yet to join rehearsals at Glyndebourne to bring Smyth’s passionate and rich score to life; up to this point, Ticciati, Still and the cast have had only fragments of recordings; rehearsals have been with a pianist repetiteur rather than the full orchestra. And what will it sound like?

“When you don’t know a composer and their language, you start by comparing their music to others,” says tenor Rodrigo Porras Garulo, who sings Marc. “She has such a big vocabulary that sometimes you think you’re singing Cavalleria Rusticana, sometimes you think you’re singing Debussy, sometimes a Schubert song, other times Irish folk songs. It’s very mixed, and that’s the beauty of it.”

“My role starts with light French melodies, then there’s a dramatic duet, then I have a crazy full-on aria where I have to murder a rat, and by the final act I’m doing my best Wagnerian dramatic soprano interpretation, high and loud,” Fagan says.

Much of Ticciati and the music team’s work these past two years has been detail-focused as they sought to create the Ur-score. “We’re sharpening, chamfering, varnishing everything to make it have the wings so that it can fly,” Ticciati says. Smyth never even got to hear her opera as she had first written it. “At the same time as thinking: ‘What did Ethel want?’, we’ve also been asking ourselves: ‘What can we do to make this piece live at its best?’”

For everyone involved, the freedom of not having previous recordings or productions to refer to is exhilarating – and scary. “Actually that’s made me a bit nervy … that every person who comes to see this will never have heard it in this way,” says Lloyd-Roberts. “That gives us a different kind of responsibility and obviously we want this opera to be a huge success.”

“I hope it’s a beautiful assault on our senses – and on our expectations,” Still says. Ticciati is confident the drama and power of the music will speak for itself. “I hope that it’s going to be tidal and it’s going to hit audiences in the face – whhhooomph!”

• The Wreckers is at Glyndebourne festival from 21 May to 24 June, and at the BBC Proms on 24 July. The production will be available to watch later in the summer on Glyndebourne Encore.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News