‘The Shining’: THR’s 1980 Review

On June 13, 1980, Warner Bros. bowed Stanley Kubrick’s psychological horror film The Shining in theaters nationwide. The film, starring Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall, went on to gross $47 million and endure perpetually as one of the titles routinely mentioned as among the scariest movies of all time. The Hollywood Reporter’s original review is below:

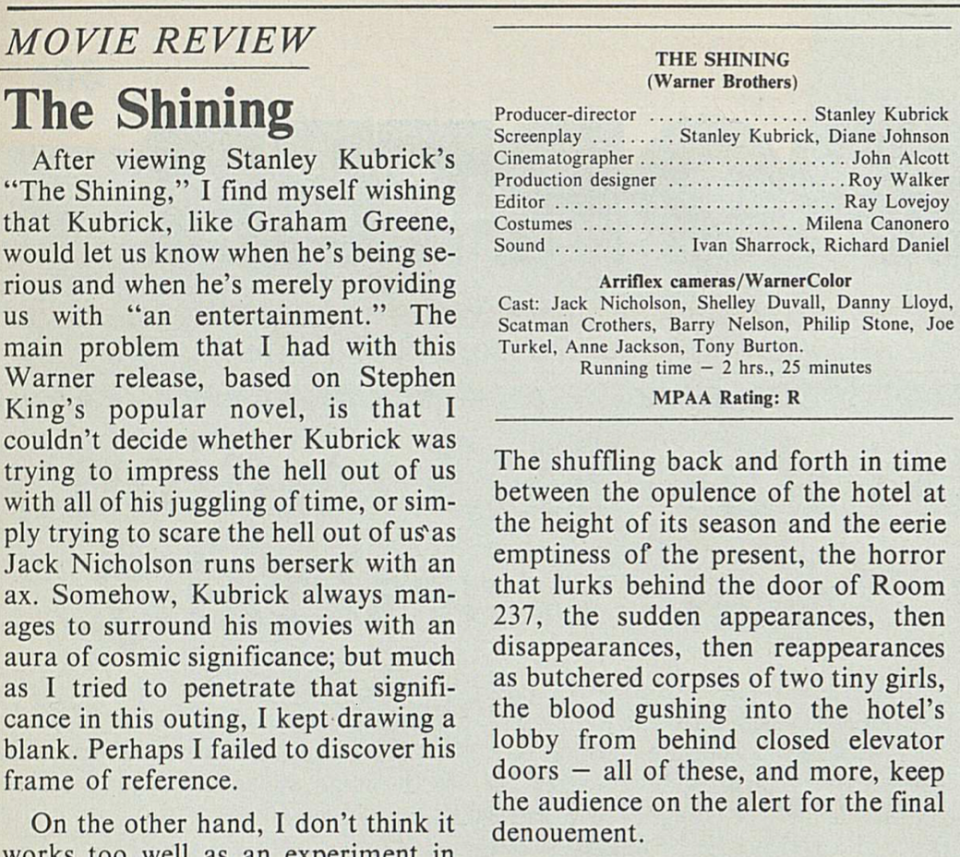

After viewing Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, I find myself wishing that Kubrick, like Graham Greene, would let us know when he’s being serious and when he’s merely providing us with “an entertainment.” The main problem that I had with this Warner release, based on Stephen King’s popular novel, is that I couldn’t decide whether Kubrick was trying to impress the hell out of us with all of his juggling of time, or simply trying to scare the hell out of us as Jack Nicholson runs berserk with an ax. Somehow, Kubrick always manages to surround his movies with an aura of cosmic significance; but much as I tried to penetrate that significance in this outing, I kept drawing a blank. Perhaps I failed to discover his frame of reference.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

On the other hand, I don’t think it works too well as an experiment in Gothic horror either. Here Kubrick has substituted for the familiar old dark house a vast luxury hotel somewhere in Colorado, snowbound and shuttered for the long winter months. Nicholson, with his wife (Shelley Duvall) and their young son (Danny Lloyd), has been hired on as the resident caretaker through those months by Barry Nelson (who manages to look disconcertingly like both Jack Kennedy and Ronald Reagan). Nelson, in an overly protracted sequence that sets up the plot, informs Nicholson (and us) of a gruesome ax murder that had taken place at the hotel years before. The solitude had presumably driven that earlier care taker stir-crazy, and he had murdered his wife and their two children.

That should have been enough — but not for Kubrick. The “shining” of the title refers to an extrasensory perception shared by the boy and Scatman Crothers, the hotel’s master chef. While it doesn’t do them much good in the long run, it sets the audience up for some kind of reprise of The Exorcist, especially since the child is clearly possessed from time to time by a completely different, and malignant, person. But, astonishingly, when the chips are down and the maddened Nicholson is pursuing him, ax in hand, through a wintry maze, it isn’t his “shining” that saves him, but a trick I learned as a Boy Scout — and that doesn’t help the picture either.

It’s a handsome film, though, strikingly photographed by John Alcott in wintry settings that include both Colorado and Oregon. As is his custom, Kubrick has compiled an effective score from the music of such modern composers as Bartok, Ligeti and Penderecki — augmented by weird shrieks and electronic thumps. The soundtrack alone can keep you on the edge of your seat. And I must admit that, after its lethargic beginnings, so does much of the picture.

The shuffling back and forth in time between the opulence of the hotel at the height of its season and the eerie emptiness of the present, the horror that lurks behind the door of Room 237, the sudden appearances, then disappearances, then reappearances as butchered corpses of two tiny girls, the blood gushing into the hotel’s lobby from behind closed elevator doors — all of these, and more, keep the audience on the alert for the final denouement.

Alas, it isn’t there! The screenplay, as written by Kubrick and Diane Johnson, never lets us in on what motivated these events. Were they all taking place in frustrated author Nicholson’s fevered brain? Or was some larger force, something far beyond Nicholson, at work? Was Nelson, the manager of the hotel, their instigator or their victim? And what were those two men, one masked, doing in that upstairs room — and what relevance did it have to the rest of the story?

These were the kinds of questions I kept asking myself throughout the unspooling of The Shining. Sure, it works on the superficial gut level of response to an ax murder, or of Duvall defending herself with a kitchen knife as Nicholson feverishly batters down her door or of all that blood gushing from the elevator shaft (so graphically depicted in the television ads, so pathetically left hanging there in the film itself). One has every right to expect at least quasi-logical answers even in a Gothic horror tale. The answer that Kubrick supplies in the final frames of his film raises more questions than it answers.

Whether or not Shelley Duvall knew at all times what she was supposed to be doing in the script, no one could have been more ideally chosen to register wide-eyed horror. Scatman Crothers lends all possible credence to an increasingly ambiguous role. Joe Turkel registers strongly as an elegant, impassive bartender, and Danny Lloyd is acceptably childlike or demonic, as the script demands. But for Nicholson, The Shining is a field day. Not since those halcyon years in the Roger Corman low-budget horror movies has he had such opportunity to roll his eyes, bare his teeth, smile his devilish smile or laugh so maniacally. Nicholson is obviously having the time of his life. I wonder if everyone else will. — Arthur Knight, originally published on May 23, 1980.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Yahoo News

Yahoo News