Sick of Doing Dishes, I Turned to One-Pot Perloo for My Next Quarantine Dinner

By this stage in our international quarantine odyssey—which is what? week three? week seven? episode 27 of The Twilight Zone?—I’m willing to bet that it’s not the home cooking that is sending you around the bend. It’s cleaning the dishes. In my house, especially on weekends, cooking comes in surge tides as I cater to two toddlers, two teenagers, and two adults for three meals a day, plus snacks. Each wave of eating generates a concomitant wave of scrubbing and scraping all the pots and pans and plates and knives.

On some days, I spend 12 hours in the kitchen, mostly at the sink.

It is during days like these that the phrase "one-pot meal" shimmers like a magic incantation. I have found myself dreaming of cooking a single dish that can feed everyone in the house several times over—without my counter looking like a scene from Grey Gardens. So it’s fortuitous that last week I found myself on the phone with Kevin Mitchell, a South Carolina chef, food scholar, and instructor at the Culinary Institute of Charleston. I wanted Mitchell to school me on the fine points of perloo.

Mitchell has a deep interest in "the beauty and the tragedy of Southern food," as he put it to me, and he tells his students that before they dive into any dish, "I want you to understand where it comes from." Here’s the first thing you need to know about perloo, which can also be spelled "purloo" and which shares a lineage with pilau and pilaf: Slaves created it. Centuries ago in South Carolina, enslaved Africans cultivated Carolina Gold rice on Lowcountry plantations, and the crop not only fed people but made Charleston rich. But when it came to feeding themselves, "enslaved people normally had access to only one pot," Mitchell said. "You have to be very creative." Perloo, like so many of the one-pot classics that emerged during that period of history in the South, is a dish whose layers of flavor speak to us about resourcefulness in a time of suffering.

Like jollof in West Africa and paella in Spain and biryani in South Asia, perloo uses rice as the foundation for a compounding flurry of flavors. "No matter where you go, there’s always a one-pot rice dish in the world," Mitchell said. And they’re all great, but they all succeed or fail based on how you introduce the ingredients. This is the second thing you need to know about perloo: You can make it pretty quickly, yes, but everything depends on when you throw stuff into the pot. "The order is very important," Mitchell told me.

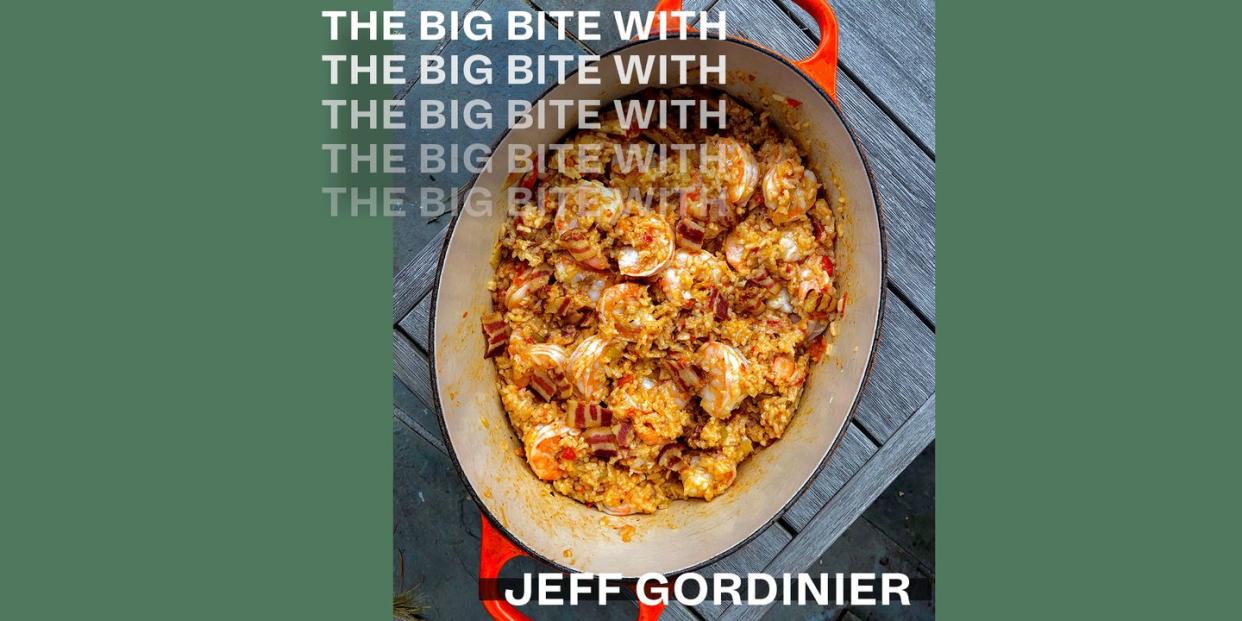

I’m not going to provide a recipe here, because there are countless approaches online, and you can choose one according to your own preferences and needs. But the core procedure boils down to this: Cut up four or five pieces of bacon, crisp them up slow and low at the bottom of a Dutch oven, remove the bacon bits when they’re ready (you’ll add them back in later on), and then use all that salty, creamy pork fat to sizzle and coat the ingredients that you’re about to toss into the heat. Think in simmering waves: Onions and celery go first, then garlic and salt and pepper, then maybe half a cup of white wine, then maybe some chopped-up canned tomatoes, then the rice and broth and butter.

Feel free to improvise along the way. Think of the rice as a party host who can graciously accommodate all sorts of random guests. When I made perloo at home on Sunday, I decided to throw in two bay leaves (when I dumped in the tomatoes), and to sprinkle in some Vietnamese purple stripe garlic powder from Burlap & Barrel, which has an MSG-ish knack for making flavors go supernova. Instead of fresh bell peppers, which I didn’t have on hand, I used roasted red peppers from a local deli. Sadly, I didn’t have any okra, but if you do, use it. (Or send me some. I love okra.)

Now, here comes the most crucial step, and the one where Mitchell’s expertise can make a lifelong difference in your understanding of one-pot cooking: You add the raw shrimp at the very end. (Because I admittedly have become increasingly skittish about going to the supermarket, I had scored my seafood through a delivery from the Fulton Fish Market.) If you’ve ever endured a jambalaya rendered inedible by nubs of mealy shrimp, you grasp how important this is.

When you open the cover on the Dutch oven and the rice is almost ready and giving off steam, you dump all the uncooked shrimps into that perloo sauna and stir them around, letting the residual heat do the work for you. "You wait until those last three to five to maybe eight minutes to throw the shrimp in," Mitchell said. If you do it earlier, the shrimp disintegrate and "you lose that flavor and that dish is ruined." Do it at the correct moment, and the shrimp will meet your teeth with that telltale pop of freshness.

Oh, yeah, at this stage you’re also scattering the bacon bits on top. So what we’re talking about is basically a big, beautiful pot of shrimp/bacon/rice stew. Even if you’re cooking for little kids, there probably aren’t many people in the house who are going to say no to that.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo News

Yahoo News