Sister of infected blood scandal 'glad' he can't see scale of tragedy

The sister of a former boarding school pupil where boys with haemophilia were infected with contaminated blood said she was "glad" he could not bear witness to the scale of the tragedy. More than half the haemophiliac students treated at Lord Mayor Treloar College in Hampshire during the 1970s and 1980s have since died.

During that period, several pupils received haemophilia treatment at an NHS facility located within the school grounds while continuing their education. It was later discovered many had been given plasma blood products contaminated with hepatitis and HIV.

It was part of the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS, which saw tens of thousands of people infected with contaminated blood or blood products. An estimated 3,000 people have died nationwide as a result, while those who survived have lived with life-long health implications, and compensation costs are expected to reach at least £10 billion.

READ MORE: Judge tells why he can't jail bowling rampage twins as he condemns 'ITV' family

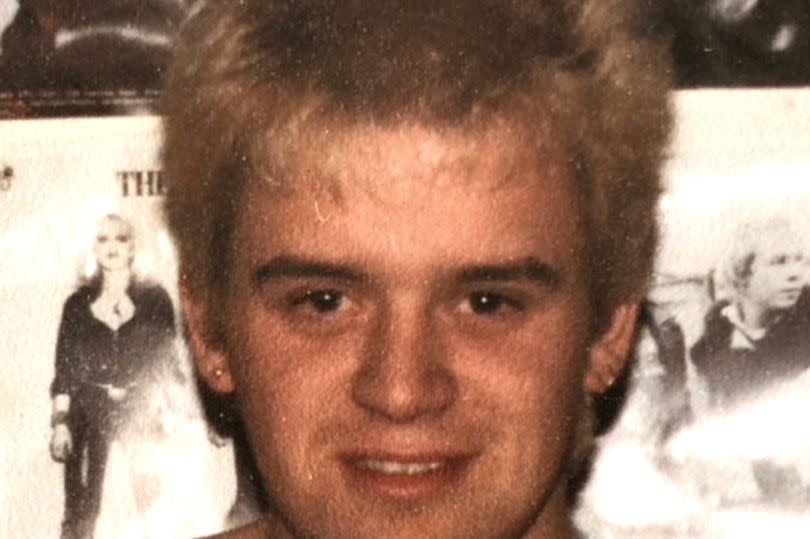

An inquiry, the largest ever carried out in the UK, was launched in 2017 by then-prime minister Theresa May, with its report to be published tomorrow, Monday, May 20. Jamie Jones, from Coleshill, said her late parents never got over the fact her brother Mark Payton became infected with both conditions.

He died aged just 41, having spent seven years at the Treloar's from aged 11 in 1972. Ms Jones said: "He was there until 1979, he actually stayed on, he loved it that much.

"He couldn't wait to get back there after breaks, he would be counting down the weeks to go back, he absolutely loved it. To be honest I'm glad he's not here to witness what we are seeing now it would have really affected him."

The 59-year-old, whose brother was four years older than her, added: "My parents never got over it, the fact he was infected. They thought they were doing the best for him, sending him to Treloar's to get a decent education.

"He missed a lot of education, most of his schooling when he was small was done on the children's ward at the hospital in Birmingham. They really thought they were doing the best for him.

"Our parents have died in the last two years so I haven't got to tell them that. They were more than happy the inquiry was happening but unfortunately they have both passed away without any recognition for their son dying at all."

"I'm his only sibling so there is just me left to fight for him now."

Of 122 boys treated at the school for haemophilia between 1970 and 1985, some 75 have since died. Steve Nicholls, 57, from Farnham, Surrey, attended the school between 1976 and left in 1983.

In his class of 20 boys, just two are still alive. "During the time we were there we were blissfully unaware of what was going on behind the scenes," he told PA.

"At that time we were treated very well, we had the best life experiences, we were basically left to get on with being young teenage boys. We became like brothers because we grew up together, we ate together, we played games together, we learned together and we were treated together."

"So the bonds that were formed there were very, very strong, very strong." He described the harrowing experience of seeing classmates fall ill: "It wasn't uncommon to see our peers becoming yellow and jaundiced, which we now know was hepatitis.

"But we were just told: 'Not to worry about you'll be all right. Just carry on as normal, go and play football, go to lessons as normal.' And it was the norm, we knew no different, we had no suspicions."

Mr Nicholls, who contracted both hepatitis B and hepatitis C, spoke about his current health struggles: "It's not good, I mean we just plough on and make the most of every day because we don't know how long we got left. We're a strong old bunch there and that was driven into us at Treloar's, you know, to strive and to achieve."

"We all left there, got good jobs, formed good careers, and worked for as long as we could until our health failed us. And now we're in a position now where none of us can work. None of us have pensions. None of us have mortgages, none of us can get life insurance."

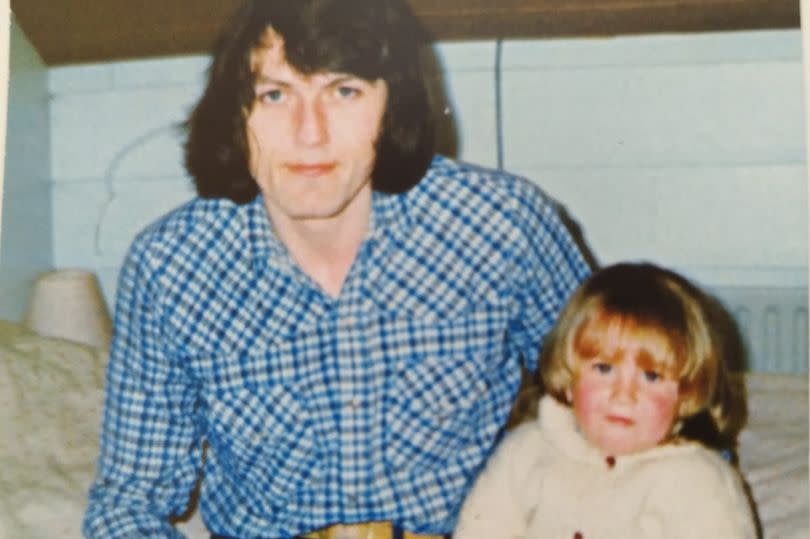

Becka Pagliaro's father, Neil King, also suffered from co-infection with HIV and hepatitis C due to treatment for haemophilia. He died in 1996 at the age of 38.

Mr King was a pupil at Treloar's in the 1970s and remained local for his ongoing treatment at the centre. Ms Pagliaro said: "He went there for all of his schooling, he didn't go back home afterwards and stayed in the area and carried on getting his treatment from the centre there right up to his death."

"They were very close to him, the doctors there almost felt like family. It feels like a big betrayal."

In a statement, Treloar School said: "This national scandal has devastated countless lives, including those of our former students and their families. Rightly, a public inquiry was set up to understand what happened and we have been a part of that process.

"We await the report's publication and hope that it provides our former students who were infected, and their families, with the answers they deserve. We fully support their calls for the Government to accelerate compensation payments.

"Students and their families placed their trust in the doctors and medical professionals who provided treatment in the 1970s and 80s. It has been shocking to discover, through the ongoing public inquiry, that some of our students may have received treatment which was unsafe or experimental."

"Recently, we welcomed some of our former students back to our school. They visited the memorial to those who died following treatment with infected blood products, which is in our school chapel. We understand and support the need for a more public and accessible memorial, and want to work with our former students and families to achieve this."

Yahoo News

Yahoo News