Smear test: Fear, pain and misunderstanding keep women from undergoing a life-saving procedure

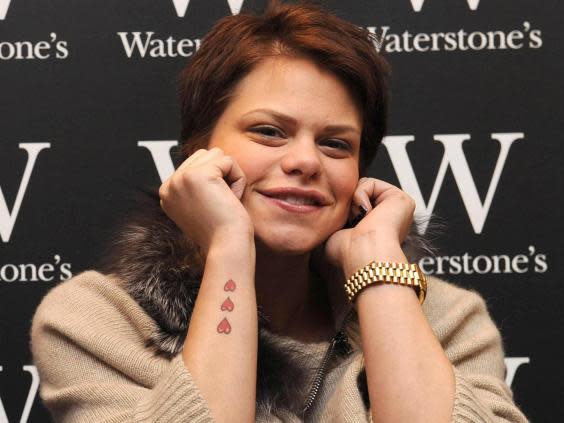

In March 2009, when reality television star Jade Goody died of cervical cancer at the age of 27, it sent shockwaves around the country. Cervical screenings saw a massive spike. In 2008-09, samples from women checking for abnormal cells shot up by 400,000.

But the so-called Jade Goody effect was short-lived. Today, 10 years on from Goody’s death, the number of women going for their routine cervical screening test is at a 20-year low. Data from Public Health England (PHE) shows that over one in four women eligible for a screening do not make an appointment after receiving their reminder letter. For younger women in London, this rises to one in two. Yet around 690 women die each year in England from cervical cancer. The sad news is that PHE estimates 83 per cent of those deaths could be prevented if everyone went to their screening.

Young women between 25 to 49 are supposed to get tested every three years, but getting an appointment can be difficult. As Charlotte, a 30-year-old picture editor, says, trying to fit in a cervical screening around work in London is not easy, especially when the nurses who perform the test only visit her clinic once a week, on varying days.

“It’s made harder as you’re advised to only book an appointment if you’re halfway through your cycle to ensure there’s no bleeding, so if you include those other factors it becomes near impossible to get something pencilled in,” she says. “I was sent my letter about coming in for one well over a year ago now.”

Charlotte was once advised to go to her local sexual health clinic to get the test, where she could just walk in. But she found out that clinic did not even offer them.

This view is echoed by Jade, a 36-year-old writer who lives in Belfast. She received her last invitation letter before Christmas 2017, but did not manage to book an appointment until the following April.

“I found it very hard to coordinate with my GP surgery; there’s only one nurse who does it, and she’s only available a couple of mornings a week,” she says. “Add in my commitments, her annual leave, and working around my periods too, and I think I waited about four months in the end.”

PHE has not set specific targets for its campaign, but aims to raise awareness of cervical cancer risks and estimates an increase in women taking a test – they hope for an extra one to three samples taken every two months at each GP practice.

“It’s particularly frustrating, especially now with all these campaigns being run,” adds Charlotte. “Either they need to make doctors do them too, or if nurses are limited, make it so women are allowed the time off work to ensure they are getting them done.” The NHS website says tests are usually carried out by a female nurse or doctor, but this can vary from practice to practice.

Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust is one of the charities working with the NHS and PHE to carry out the latest campaign and get more women tested.

“Part of the PHE campaign is to raise awareness and get different stakeholders involved, like GPs and those who provide or promote the service, to ensure there is availability of appointments, especially at weekends and in the evenings,” says Kate Sanger of Jo’s Trust. “It’s great to raise awareness but in conjunction there needs to be that service of provision.”

The cervical screening test, once known as the smear test, normally takes around five minutes. A speculum is inserted into the vaginal canal to open up the cervix and allow the nurse to insert a small, soft brush to take a sample of cells.

There are myriad reasons women do not get tested. A recent poll of 2,000 women aged 25 to 35 found that 81 per cent feel embarrassed about cervical screening tests, 80 per cent felt body conscious, 71 per cent were scared and 67 per cent felt they did not have control over the process.

Another barrier for women is understanding and talking about HPV, a common virus which normally clears up of its own accord but can, in some cases, lead to cancer.

“I actually had no idea what HPV was, and was mortified to find out it was a strain of the herpes virus,” says Lucilla, a 30-year-old singer in London. When she learnt she had an STI she said she felt ashamed and that “it was basically like admitting to my mum that I’d had unprotected sex... horrifying”.

The HPV vaccine can be seen as another factor contributing to record low numbers of women getting tested. The vaccine was introduced in 2008 and effectively protects women from developing the types of HPV that causes 70 per cent of cervical cancer cases. However, as Jo’s Trust advises women, the vaccine alone does not ensure women are immune from cancer, or different HPV strains. Only when combined with the screening test is the vaccine most effective.

Campaigns encouraging women to get a cervical screening test have been accused of minimising or trivialising women’s experience and fear of pain. One recent slogan, “Don’t be a diva, it’s only a beaver”, went viral on social media.

“Our argument is it’s not always easy and there are many reasons why women don’t attend or find it difficult to attend,” says Sanger (Jo’s Trust was not responsible for that “diva” campaign). “We never blame or shame women for not going – we want to find out why.”

These reasons can include language and cultural barriers, a physical disability or a learning difficulty, sexual assault, traumatic birth, or a health condition such as chronic pelvic pain or endometriosis. The test can also be more painful for post-menopausal women, whose vaginas tend to be drier.

Vanessa Holburn, a 49-year-old author living in Berkshire, says she avoided going for a cervical screening test for six years after having a “nightmare delivery” with her first child, who is now 13. But she says the cervical screening has changed for the better by, for example, replacing cold metal speculums with plastic devices.

“I would say that nothing is ever as bad as you can imagine it, and in the worst-case scenario you can ask them to stop,” she says. “The process has come on incredibly in recent years and nurses are trained to deal with those that may be worried. You aren’t the only one that feels this way – and you’re allowed to say so.”

I would say that nothing is ever as bad as you can imagine it, and in the worst-case scenario you can ask them to stop

Vanessa Holburn, 49-year-old author

For most people, a cervical screening test might not be a very painful experience. For others, according to Lynn Enright, author of Vagina: a Re-education, it can be really painful, traumatic or even impossible, depending on that person’s circumstances and experiences.

“And I think it’s important that medics realise that. For some people, a cervical screening test is not a simple, straightforward procedure. Those people will need extra support and it’s vital that they get it,” she says.

Enright adds: “I’ve had cervical screening tests that were carried out by nurses in a rush – and those were more painful than others. I think nurses carrying out cervical screening tests should be made conscious of how to make a cervical screening test as painless and comfortable as possible. That should be a real priority.”

If women are worried about the screening, there are several things they can do, including booking a double appointment to ensure there is no rush, asking for a different size of speculum, or requesting to be examined in a physical position that is more comfortable.

The cells collected during the test are sent to the laboratory to check for abnormalities – not for cancer, as is commonly thought. The chance of having abnormal results are high: around 220,000 women do every year.

There are different levels of abnormalities. Depending on the grade of risk, patients might be offered treatment straight away. People in the middle, with moderate to high grade abnormal cells, are monitored much more closely instead of receiving treatment to see if those abnormalities develop or if they clear over time.

Often, the next step is attending a colposcopy at a hospital for further examination.

Lucilla has had several colposcopies, including a biopsy of her cervix, which she describes as “traumatic”.

I actually had no idea what HPV was, and was mortified to find out it was a strain of the herpes virus

Lucilla, 30

“I reluctantly got into the stirrups, and was informed that it was recommended that I watch the events unfolding on the TV screen in front of me – there was a very intimate camera at a most unflattering angle. Let’s just say I wish I’d shaved more closely,” she says.

“I didn’t want to watch, and told them so, but the nurse and the doctor in the room said they really thought it would make me feel better about the whole thing. The doctor was male and middle-aged, which made me feel weird, even though I knew in reality he spent his entire day looking at vaginas and cervixes.”

During a colposcopy, the doctor will insert the speculum into the vaginal canal, shine a light into the cervix and then spray liquids which show up any abnormal cells. If the doctor wants to examine the abnormal cells further, a small biopsy will be performed, which Lucilla says feels like “sharp, pinchy cramps”.

“I have to say I found this part a little traumatic, especially since I had an up-close view. I still feel a bit squeamish thinking about it, having had it done again since,” she says. “It wasn’t pleasant, but it was done, and that was the main thing.”

Lucilla had some cramping and spotting for a couple of days after. She had two more abnormal results in the following years, but she is now back to having a normal cervical screening test every three years.

Further treatment for some patients may be required. The large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) is a common procedure which involves inserting a thin wire loop, heated with an electric current, to remove abnormal cells. It is delivered under local anaesthetic.

After treatment, the NHS warns of side effects such as “mild pain” that lasts for a few hours and “light vaginal bleeding” that can last up to four weeks.

Journalist Rhiannon Lucy Coslett wrote in 2014 of her LLETZ procedure: “I can testify that the treatment is painful. Without wanting to go into too much detail, imagine being scraped out with an electrically charged spoon.”

Among several Facebook groups seen by The Independent, there have been hundreds of reports of negative long-term effects, such as pain, and the loss of ability to orgasm or feel aroused.

Shoshanna, 27, from Shrewsbury, says her LLETZ procedure “completely changed [her] life for the worse”, and claims doctors lied to her about the “severity” of the procedures to correct abnormal cells.

“I feel completely violated by the sexist attitude in the medical industry and I’m suffering as a result. If I’d realised that you can clear up CIN [abnormal cells] without surgery I would never have done it and I’d never have done it if I’d realised how much of the cervix they remove,” she says.

Shoshanna insists that through diet and lifestyle changes, instead of surgery, the cells might have cleared up on their own, though there is little scientific evidence to back up her statement – or to disprove it. One reason Scotland upped the starting age for cervical screenings from 20 to 25 in 2016 was because younger women were frequently coming back with abnormal results after getting a test and receiving unnecessary treatment as, especially with younger women, HPV and abnormal cells often clear over time.

“There is such little research into the cervix itself which is incredibly sexist,” she adds. “I was told to my face by a GP that the cervix had no nerves in it – recent research says that’s not true – and that my symptoms that all started after the LLETZ were unrelated.”

Kate Sanger of Jo’s Trust says that treatments for abnormal cervical cells are considered safe, and save lives.

“As with all treatments, there are some possible risks which can include narrowing of the cervix (cervical stenosis) or a slight risk of preterm birth,” she says. “You will only be offered treatment if your colposcopist decides this is the best possible action for you and their decision will be based on things such as the severity of abnormal cells, your history of abnormalities and your personal circumstances.”

If you are worried, Sanger advises to speak with a health professional you trust to ask questions and make an informed decision.

The good news is that cervical screening procedures are improving all the time. While the PHE campaign is considering how to make better use of technology, like sending text reminders for appointments, other future changes might be more radical. This includes more women inserting swabs themselves at home to test for HPV – as happens in countries like Denmark and Australia – as well as the rollout of HPV vaccines. In Wales, laboratories first test for HPV rather than just for abnormal cells – a more effective test for those who are more likely to get cancer – and this will also happen in the rest of the UK this year.

As a result of these changes, younger women might only have to get tested every five years instead of three.

Despite the valid and numerous obstacles for many women in getting a cervical screening test, the procedure is generally quick, free and is successfully keeping women alive. However, taking the test is only the first step in a quagmire of other issues, including a lack of data surrounding women’s health. Until the medical profession obtains more evidence-based and researched studies into women’s bodies and their pain, health institutions and campaigners may come across continued hurdles in encouraging women to take their health seriously, no matter the risks.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News