Sondra Locke, Clint Eastwood and the tragic disappearance of a Hollywood trailblazer

Sondra Locke didn’t like to tell people the year of her birth. The American actor and filmmaker’s death in 2018 took six weeks to make the news, so she probably wanted to keep that a secret, too. She had a certain quality to her. Unusual, inscrutable, neither here nor there, Locke could look wan and boyish or arrestingly hyper-femme. She could seem aged or ageless; resolutely human or pitched to our planet from the far reaches of space. She was one of 20th-century cinema’s most fascinating figures. You may have never once heard her name.

In 1969, Locke earned an Oscar nomination for her very first movie, a largely forgotten adaptation of Carson McCullers’s The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter. She followed it up by playing one of American film’s first trans characters in the lurid psycho-thriller A Reflection of Fear. A hard pivot like that reflected Locke’s tastes, her disinterest in the Hollywood game, and her unconventional approach to life and love.

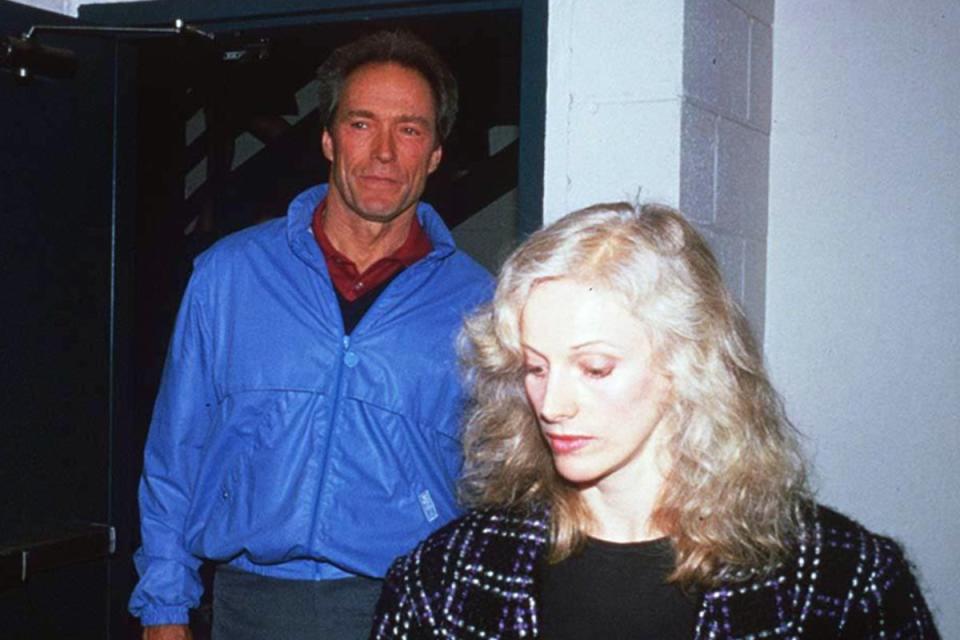

On that note, she was happily married to a gay man for more than 50 years, with 13 of those years spent cohabiting with her most prolific screen partner, Clint Eastwood. It was a romance that would aid, then derail, and then cruelly define her career, with one US magazine referring to her as little more than Eastwood’s “embittered ex” in the headline of her obituary. She also made her own movies, grabbing a seat in the boys’ club of Eighties filmmaking with work that, for better and for worse, no one else dared make.

People did eventually figure out Locke’s age: she’d shaved a few years off to get the part in Lonely Hunter, then just kept up the jig. Locke’s 80th birthday would have been on 28 May. It may have passed without fuss. But what if it didn’t?

Locke is part of a lineage of female creatives – among them the late screenwriter Diane Thomas and the producer, writer and production designer Polly Platt – who smuggled their way into the studio system of American film in the Seventies and Eighties, only to fade into relative obscurity thereafter. Locke’s disappearing act had its own specificities, though. As a movie star, she had a degree of industry power that many of her female filmmaking peers did not. But she also had a very famous boyfriend in the form of Eastwood, and as their relationship fractured, she found it impossible to crawl out from under his shadow.

In her acting work, Locke possessed a delicate, alluring strength, which presented as fragile or eerie depending on the role. The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter and A Reflection of Fear, released in 1968 and 1972 respectively, cast her as bored outsiders, teenage girls with innate buoyancy, who’ve nonetheless been preternaturally hardened by life. In the psychedelic thriller Death Game, made in 1974 but not released until 1977, Locke is one of a pair of psychotic women who take a man hostage when they show up on his doorstep. She is breathtaking in it, wide-eyed, erratic and erotic. She’s less interesting, though, in 1971’s Willard, in which she plays third wheel to a boy and his army of rat friends. (Yes, more rats!) Disappointingly, it’s likely her best-known film that didn’t star Eastwood.

I had a life before Clint and I intend to have one after

If none of those movies propelled Locke to the A-list, it may have been a case of bad timing. It feels significant that her career seemed to sputter with the arrival of Sissy Spacek, who too possessed a vulnerable, alien beauty, but had the good fortune of breaking out in significantly better films. “I learned quickly that it really doesn’t make much difference whether you’re the best for the part, or whether you have talent,” Locke once said. “It’s a matter of some fluky thing that can’t be described.”

Eastwood entered Locke’s life during a professional lull. So eager for a break, she reduced her salary to play the female lead in his revisionist Western The Outlaw Josey Wales in 1975. Like many of Eastwood’s leading ladies, Locke’s character is sharp and sassy – but doomed. Yes, she’ll get to run off with the hero in the end, but only after experiencing brutality first. Ghoulishly, her characters are gang-raped or almost gang-raped in four of the six films she made with him.

She wrote in her 1997 memoir The Good, the Bad and the Very Ugly that she and Eastwood were instantly besotted with one another. It didn’t matter, either, that they were both involved with other people: Locke was in a platonic marriage with her gay best friend, whom she’d known since she was a teenager, while Eastwood was married to a woman he didn’t live with and reportedly barely saw. However atypical it was, it worked.

On screen, Locke played opposite Eastwood and an orangutan in the dismal Every Which Way But Loose and its sequel, but otherwise played characters for him who bore increasing strength and complexity. The Gauntlet, released in 1977, luxuriates in her pissed-off glamour as a gangster’s moll on the run, while she is the vengeful antagonist of Eastwood’s penultimate Harry Callahan movie Sudden Impact, in 1983. Their collaborations also kept her trapped, though. “If you were in Clint Eastwood movies, you were in the Clint Eastwood movie business,” Locke said in 1997. “You weren’t part of Hollywood. This became clear early on. People stopped calling. They automatically assumed I was working exclusively with Clint.”

That tension only worsened over time. “You get into a rut being associated with Clint ... you get into a rut because you’ve been around a while, and everybody wants the new girl on the block,” she said in 1983. “In order to get out of those ruts, you have to have your own idea, your own project.”

The project was Ratboy, a strange Hollywood satire about a lonely window dresser who attempts to monetise the half-rat, half-human she stumbles upon at the dump. It’s ambitious but a fiasco, like ET meets Pretty Woman. There are shades of Locke’s personal frustrations in the script, pointed observations about celebrity and outsiderness. But also a whole lot of mess. “What was the point?” asked critic Roger Ebert in his review of the film. “Ratboy is very odd, but not in an interesting way.” Locke would later say the film was misunderstood by its backers at Warner Bros and cut to pieces in the editing room.

Meanwhile, Locke and Eastwood were on the outs. By most accounts, Eastwood is a taciturn fellow, with much in common with the elusive drifters that made him a star. So imagine dating the guy. An interview with Eastwood published in The Independent in 1997 cast him as a man who doesn’t so much end relationships – both professional and romantic – as silently withdraw from them until the other person gets the hint. While Locke was in the early stages of filming her Ratboy follow-up Impulse, a much better movie starring Theresa Russell as an undercover cop losing her senses, Eastwood called to inform her that he’d like her to move out of their Bel-Air home. Locke was confused, begging him to reconsider. He agreed, telling her that they should delay discussions about a breakup until Impulse had wrapped. But when Locke next came home, the locks had been changed and her belongings put in storage.

“He had every right, if he didn’t love me, to end the relationship,” Locke told The Independent, in that same Eastwood interview. “But he didn’t have the right to treat me that way. That’s where the line is drawn with Clint. He has all the rights and you have none.” Eastwood, meanwhile, said that he had ended the relationship due to Locke’s marriage to her friend Gordon Anderson. “She spent 98 to 100 per cent of her time coddling him,” he claimed. “I was bored with it. At some point, you go, ‘I want a normal relationship in life. I want a girl for me’.”

An unusual, year-long legal battle ensued, with Locke fighting for palimony despite the fact that both she and Eastwood were legally married to other people. Locke accused Eastwood of abuse, and alleged that he had ordered her to have two abortions and a sterilisation operation – claims Eastwood “adamantly denied”, while arguing that Locke’s suit was “unfounded and without merit”. In his own depositions, Eastwood would refer to Locke as merely his “occasional roommate”. In the end, and simultaneously exhausted from treatment for breast cancer, Locke settled, taking ownership of one home bought by Eastwood, $450,000 (at the time, £251,000) in unpaid earnings from Eastwood’s production company, and – at her request – a production and directing deal with Warner Bros.

While Locke at first claimed victory, she later alleged that the Warner deal was a sham – she had been paid $1.5m and had an office on the studio lot, but more than 30 projects that she brought to them were turned down. Then she discovered the $1.5m secretly came from Eastwood, and not Warner Bros. She sued him for fraud. Eastwood claimed that his intentions were pure, and that he financed the deal to help Locke. She claimed that it was a deceptive power play designed to trap her at the studio and keep her out of work.

The case went to trial in 1996, with Eastwood accusing Locke of using her cancer diagnosis to garner sympathy from the jury, and insisting that the suit was a shakedown. They eventually settled out of court for an undisclosed amount – both parties insisted they had won. While promoting her book in 1997, Locke confessed that she wished she “understood who [Eastwood] was” earlier. “I just feel like, oh my God, I’ve lost so much time.” Her book, she said, was an attempt to put across her side of the story, and take back a narrative that had painted her as an obsessed gold digger. “I had a life before Clint and I intend to have one after,” she said.

Locke’s career never recovered, and she said in 2013 that she believed she was blacklisted as a result of her legal feuds. “No one wanted to get on [Clint’s] bad side,” she told Wand’rin’ Star. “Why bother? Why get involved? I will always believe that I had many fans in high places, but they were not willing to put themselves on the line. That is very expected in Hollywood.”

Little is known of Locke’s life in the years after. She remained married to Anderson and starred in a single film, an indie romcom called Ray Meets Helen, in 2017, but otherwise went dark. She was not included in the “In Memoriam” section of the Oscars in 2019, and Eastwood made no public comment on her death from bone cancer. It is unclear whether they ever spoke again. Curiously, though, Eastwood’s 2018 film The Mule saw his character reconnect with the ex-wife he spurned and mistreated, seeking redemption as she dies with cancer. It hit cinemas a day after Locke’s death was announced.

Every once in a while, Locke’s name is invoked in articles about the history of women in Hollywood – many outlets also re-examined her battles with Eastwood during the high-profile stand-off between Johnny Depp and Amber Heard, a situation that bore slight parallels. But her actual work is worth revisiting, too, however zany much of it is. Locke was distinct, unusual and brilliant, a woman born for a Hollywood that didn’t quite exist at the time she got there. But while it hurt her, it never broke her.

“All in all I am happy with myself,” she said in that 2013 interview. “I feel that I have met the challenges meted out to me with as positive a face as anyone.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News