Spector on Sky and NOW review: an excellent account of the famous producer’s fall - and why it took so long

Twenty years ago, a four part Phil Spector documentary would likely have opened with a montage of his timeless teen symphonies, interspersed with gushing tributes from Bruce Springsteen or Amy Winehouse, or any of the many, many artists to whom he was a direct inspiration. But then February 3, 2003 happened. And so – inevitably; rightly – we instead begin here with the 911 call made by his chauffeur that night. “I think my boss killed someone,” Adriano De Souza says. Why, the operator asks. “Because... he, he have a lady on the floor and he have a gun in his hand,” he stammers in response.

The lady in question was of course Lana Clarkson. And it is to directors Sheena M Joyce and Don Argott’s great, great credit that she is here three-dimensionalised, rather than referred to – as she was during much coverage of the murder trial – as ‘a B-movie actress’. Her story – her full story – is as much the focus here as Spector’s.

In fact, the makers deserve further credit for producing something that, in recent times, has seemed obsolete: a documentary that approaches its subject matter with zero agenda, allows people from both sides of the story to have their say, then allows the audience to make up their own minds about how they feel.

Spector’s many famous collaborators don’t, understandably, feature much. But we do get an extensive list of interviewees, including defence attorneys from both sides, journalists who met Spector, Clarkson’s friends and family, the police, eye witnesses and the guy who made his wigs (in a rare moment of dark levity, he pops up just after a section in which a BBC documentarian recalls being berated by Spector for even suggesting that he wore them).

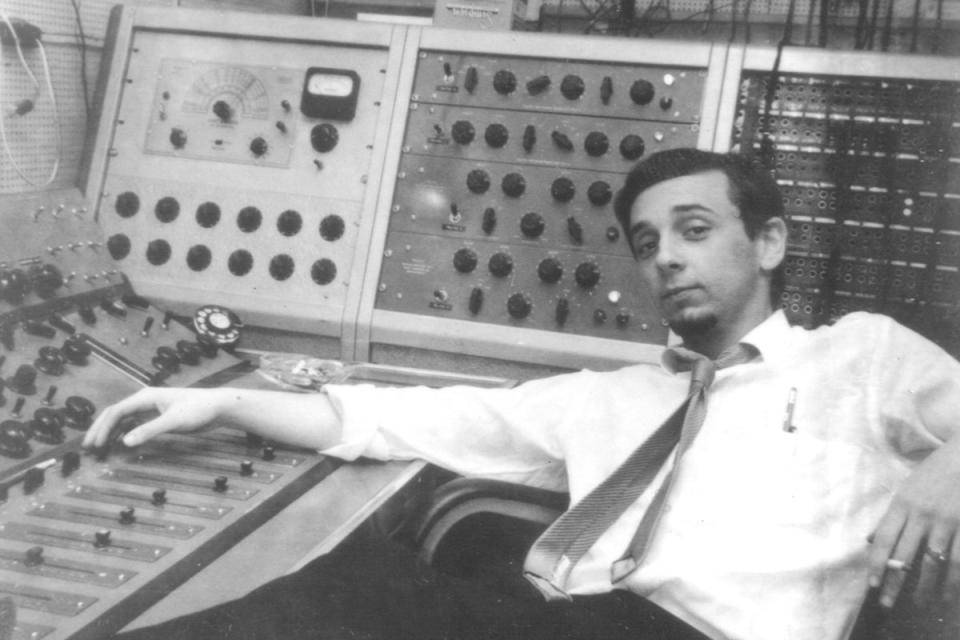

The music and Spector’s rise is dealt with relatively quickly. His father died by suicide when Spector was ten. By 18, he had written, arranged, played, sung and produced a Number One single (To Know Him Is To Love Him by his group the Teddy Bears), an absolutely unheard of feat at the time. His imperial run of girl group productions was underway, peaking in ’63 with the Ronettes’ Be My Baby. Then the Beatles turn up and start writing their own stuff, and by the ’70s the modern day template for the producer as a mere backroom overseer, rather than the star of the show, is established.

It is here that the disturbing stories start. Spector fires a gun at a session with John Lennon. He threatens Leonard Cohen with a gun while recording. He threatens the Ramones, with a gun. We hear how he would never let people go home. And how Ronnie Spector – by then his wife – was locked in his mansion and only allowed to leave in a car with a blow-up doll version of her husband seated next to her, lest anyone dare to converse with her.

The problem, really, is that for more than three decades, as it has so many others, Hollywood facilitates him carrying on like this because it’s thought to be somehow all part of his genius creative process. When Cohen is asked why the hell he would remain at a session when someone had pointed a gun at him, he pretty much explicitly says this.

The night Spector meets Lana Clarkson, he goes out for dinner with a female companion. When she goes home, he tells the waitress who has been serving them he’ll be taking her out instead. They go to the House of Blues. The waitress goes home. He then cajoles Clarkson, then the House of Blues hostess, into coming back to his “castle”. Nobody, it seems, is allowed to say no to him, ever. Even as the trial begins, you get the sense that he thinks he can just buy his way out of trouble with expensive lawyers (which he almost does).

By the end of the fourth hour, we have people asking aloud the question of whether Phil Spector’s music should be allowed to live on untainted by his actions. To me, there’s an easy answer to that. It should: chiefly because another thing that becomes clear over the course of the documentary is that, while he was a maniacal control freak, Phil Spector was nothing without his collaborators.

For example, all of his biggest hits were co-written with Jeff Barry and the late Ellie Greenwich, neither of whom are really even mentioned here. Nobody knows precisely what happened in the room when those songs were penned, but who, out of the nice, polite middle class couple and the crazed, clearly troubled producer, would you bet shouted louder when the credit was being apportioned?

In 1974, Dolly Parton was told that Elvis Presley wanted to record I Will Always Love You, but that he would need 50 per cent of the publishing if he did (Parton told him – probably not using these words – to f*** off). In 2023, a collective of songwriters called The Pact – featuring people involved in hits by Dua Lipa, Justin Bieber, Britney and countless others – are still fighting against this kind of thing happening.

I’m certainly not saying that Phil Spector was not integral to the likes of Then He Kissed Me, You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin or River Deep – Mountain High. What I am saying is that there were other very, very talented people heavily involved in these records and that their work – not just the work of Phil Spector – should be allowed to live on forever.

Spector is on Sky Documentaries and NOW from Sunday January 8

Yahoo News

Yahoo News