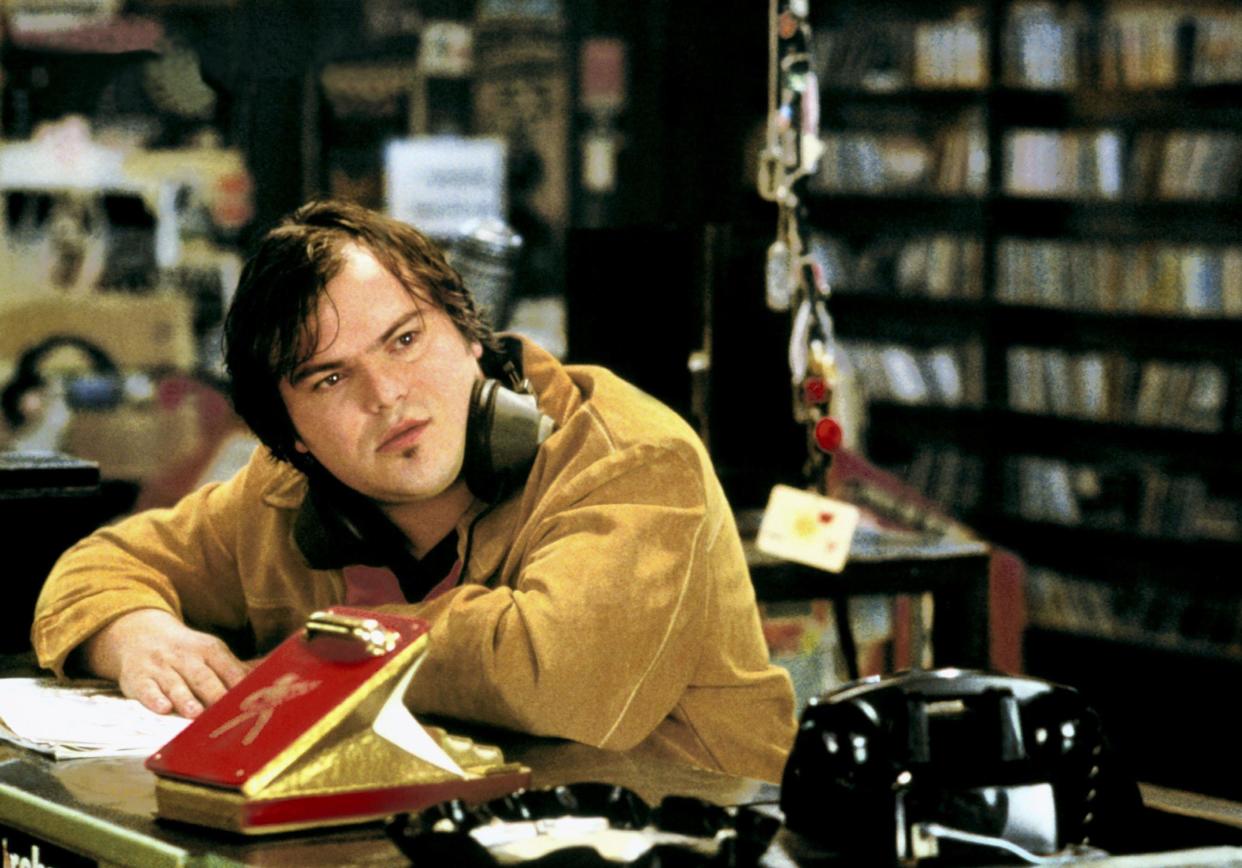

I spent my formative years working in record shops. The pay was terrible, the work tedious, but it felt like a vocation

Australia’s last Sanity store has closed its doors for the final time. This is terrible news, not least for its staff. The demise of Sanity in the physical realm (it survives online, for now) marks the official end of a bygone age – the era of the high street music franchise. An era when awkward teens with ambitious haircuts could find a first job that so perfectly captured their interests – loud music, standing around doing nothing and being rude to strangers.

As someone who spent a formative decade working in record shops, I grieve that my children will be denied this important rite of passage. Will they care? Probably not. No doubt they’ll find their own virtual spaces to share and celebrate music, but permit me this brief tribute to the halcyon days of music retail.

Related: ‘Impossible to continue’: Sanity to close remaining stores due to dominance of digital music

Back in the late 90s, there was no better first job than working in a record shop. It wasn’t just the street cred, but the sense of finding a tribe. Growing up in Perth, that tribe had proven elusive to someone who didn’t play or follow sport. The people I met through working with music became some of the best friends I ever made. I married one of them and went to the weddings of countless others.

Being into music was a serious pursuit when I was 18. It was sport for people who didn’t like sport. We each had our teams and loyalties – Blur v Oasis, indie v dance, metal v everyone – who would fight for supremacy in the charts and music press. Being serious about music meant reading (and occasionally buying) a vast range of music papers and mags with the kind of high-level research skills I rarely applied to my university studies.

It took me two attempts to pass the employment exam at my local record shop, a qualification that still means more to me than my high school graduation. (Sample question: Name the four bands Eric Clapton played with in the 60s.) This was my first taste of expertise, the sense that I knew more about something than most people. And, boy, how we chosen few looked down on most people.

What little money I made selling records went straight into buying more.

Working in record shops, big and small, gave me a warped idea of what a job was. All those necessary qualities in an employee – politeness, punctuality, sobriety – weren’t exactly discouraged, but there was an understanding they weren’t very rock’n’roll. When the manager of Tower Records Piccadilly noticed I was garrulously drunk after a liquid lunch break, the only reprimand he gave me was a Polo mint.

The pay was terrible, the actual work tedious, but it felt like a vocation. We loved the proximity to music, to art, to the material of meaning in our lives. We were practising experts, performing a public service. We were good salespeople despite ourselves, because we cared about what we were selling, even as we took pride in being appalling employees. It was the most benevolent form of capitalism. We weren’t stealing your money, we were helping you find something that would make your life better. Or, at least, a little easier to bear.

I knew the value of musical retail therapy because I was a customer as often as I was a worker. My days off, even my lunch breaks, were spent haunting racks in HMV, Virgin, Trax, Sanity or 78 Records (all now extinct in Australia). What little money I made selling records went straight into buying more. I knew the life-changing power of slipping on the headphones at the preview rack and finding your new favourite band.

What we lose with the death of the music chain store is a social hub built around art. Galleries and bookshops are quiet places. Record shops were noisy temples to gather, gossip and flirt. Generations of teens would meet after school at their local Sanity (or Tower or HMV) to swap dirty headphones and instant reviews. I knew girls who would pool pocket money on a new CD and toss a coin to see who got to keep it and who walked away with a taped copy. How many future bands were born between those aisles?

Music seems to have been displaced for new generations of teens looking for somewhere to locate their identity. The album format itself now seems like an anachronism, born out of the limits of pressed vinyl, made redundant by the infinite capacity of the digital. In an age when streaming services each offer their version of the entire musical canon, the idea of aligning yourself with a single album, artist or genre seems positively backwards.

The decline of the high street store reflects the fact that new albums rarely dominate the mainstream narrative. Few Australian media outlets still run regular album reviews. A weird side effect of the digital age is that pop culture has become more diffuse – we don’t share music with the people at the local shop, but with strangers scattered around the globe – and, as the Atlantic noted last year, you can have a massive hit song (I originally wrote “single”) without leaving the slightest impact on mainstream consciousness.

And yet. After decades of downward sliding, CD sales have made a slight recovery in the past two years. Anecdotally, surviving record shops report a renewed interest in the silver discs and parents tell me their teens are ransacking the storage room for treasures the algorithms might have kept hidden. I’ve seen how my own young children enjoy staring at the cover art and thumbing the booklets while listening to Taylor Swift, the Cranberries or the Sing 2 soundtrack.

With the loss of Sanity and its ilk from our streets and shopping centres, music worship seems destined to become a niche pursuit. Maybe it will thrive in its new underground, but it will never be the dream teenage career option it once was. Thinking back on my days working in record shops, it struck me how few of us were actually musos. We didn’t want to make music. Music made us. It changed the way we dressed and drank and danced and fell in love. More than that, it made a lousy retail job feel like the pinnacle of ambition.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News