The strange birth of Turkey – and the truth about its national myths

Koçero, an outlaw, is heading for the city of Batman in south-eastern Turkey. In his front pocket are the severed ears of a rival bandit he had spotted earlier on a bus. A Robin Hood figure to some, by the time of his death in 1964, Koçero was known far beyond his native country: even the Coventry Evening Telegraph covered the demise of “Turkey’s most notorious bandit”.

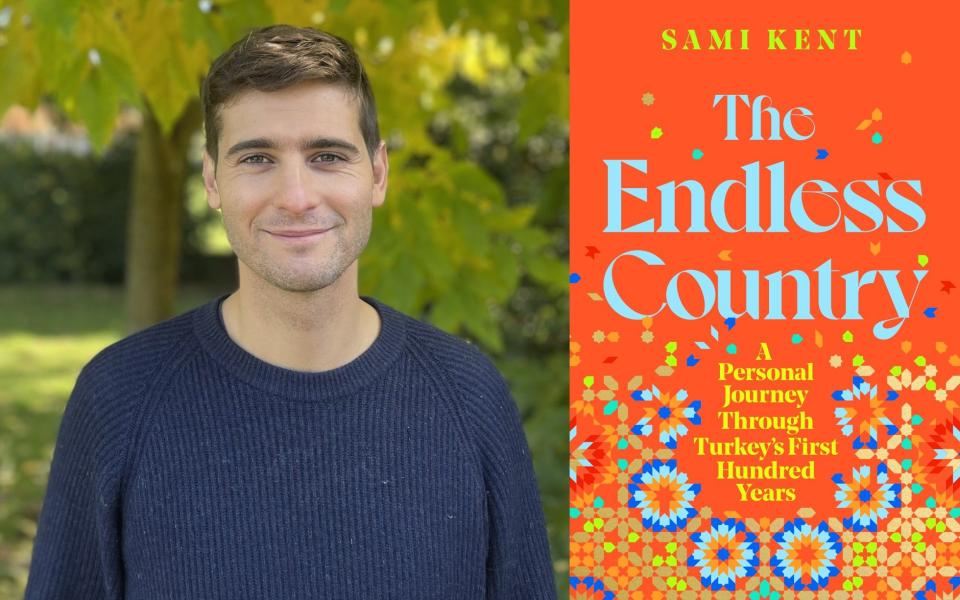

It is by way of such unexpected figures that Sami Kent conducts this “personal journey” through Turkey’s first 100 years – from the dissolution of the Ottoman empire to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Colourful case studies such as that of Koçero – and laws on hats, revolutionary sects and ice cream – are deftly employed to tell a wider story. By the mid-20th century, the oil world was booming and the countryside seethed. With riches flowing in and out, Batman became a hunting ground for the dispossessed people who populated it. That vignette of Koçero with an additional set of ears is more than gratuitous violence; it allows Kent to capture an increasingly globalised Turkey, and its quest to become küçük Amerika (“a little America”), as well as to identify who that historical shift left behind, and what many turned to: banditry. This is surely how history should be told – fun, alive, human.

Kent has reported on Turkey as a journalist for numerous publications. His father left Turkey at 19 for the UK, so The Endless Country is a strange homecoming, written with a mixture of intimacy and distance. “Gurbet” captures this – a Turkish noun for a feeling “between homesickness and exile”. Unflinching in its approach to Turkey’s troubled past, this is not a hagiography of a nation.

As he says of the “absurd” adage sometimes bandied about, “World War One was lost by the Ottomans and won by Turkey”, that story only looks like a victory when told through maps. Kent digs behind the cartographical to build an engaging and vivifying chronicle. His prose is novelistic, and often as moving as it is illuminating: “This was how the Turkish nation was born, but it was a birth like any other: out into the light, crying and confused, tender and pink.”

Turkey is revealed as a nation at war with itself about its “present”. The history of the Turkish Republic is continuously one of modernisation, changing, becoming. The not-so-roaring 1920s under Atatürk are recorded by Kent through the lens of hats – the archaic fez was outlawed, and the şapka (a European-style brimmed hat) was adopted, a symbol of all things secular and new. And Turkey’s birth as a republic – at least legally – was patchwork. In 1926, a new civil code was adopted, one near-identical to that of Switzerland; the penal code was pinched from Italy.

Perhaps that is why Turkey’s impulse to self-mythologisation features so widely in this chronicle; Kent indulges it, while remaining sceptical. Kent’s father tells him that in the 1930s, as a more strident nationalism emerged, they learnt in school that everything was actually Turkish. The quintessential example is the Sun Language Theory: that all languages were descended from one proto-Turkic tongue. Even the etymology of the river Amazon was derived from the Turkish ama (“but”) uzun (“long”) – the first to stumble across the river exclaiming: “But it’s long!” Such myth-making raises a bemused eyebrow, but it also, more significantly, exposes a nation craving a sense of rootedness following the humiliating collapse of the Ottoman empire. Kent is adroit in producing such insights, all the time with humour.

Yet this is no comprehensive chronicle of Turkey. Kent is up front about that. Some crucial events will be missed, he admits, aiming for a history more mosaic than textbook. His methodology is successful – if judged by its readability. The period of trade liberalisation of the 1980s under Ozal (which sounds so dry) is done through the creamiest of subjects: an orchid-flavoured ice cream – richer in vitamin A than breast milk – from Maraş, supposedly where the dessert originates (again, always playfully mythologising). And Erdoğan’s troubling, paranoid ascendance is mirrored by the rise of what may be the largest prison in Europe. We are never left to drown in statistics, though. Kent always keeps us above water with bewitching narratives.

A slim epilogue betrays Kent’s frustration with a story left incomplete. The May 2023 general election, which saw Erdoğan consolidate his grip on the judiciary and media, was, anticlimactically, “a turning point that didn’t turn”. Though this ending and points of this book fan out to “wider lessons”, there remains one issue with Kent’s history of Turkey: its insularity.

It is a personal history, but when mentioning Erdoğan and the democratic state of a nation where elections are not, perhaps, “free and fair”, but “free enough”, competing visions of Turkey as a nation are left unaddressed. Kent is conspicuously critical of Erdoğan, but fails to probe the president’s own political vision; what are its roots, its ambitions, its lessons for other democracies facing rising authoritarian leaders? Kent’s journey is engrossing, but, sadly, solitary. A shame, then, that he didn’t make space for his thoughts on the local elections this year, which hint towards a different trajectory.

The Endless Country is published by Picador at £20. To order your copy for £16.99, call 0808 196 6794 or visit Telegraph Books

Yahoo News

Yahoo News