Studios’ Now-or-Never Choice: Sue AI Companies or Score a Major IP Deal

Last year, Hollywood took stock of the potential — and dangers — of generative artificial intelligence. As use of the human-mimicking chatbots evolved into a sticking point in the strikes, creators took to the courts, accusing AI firms of mass-scale copyright infringement after their works were allegedly used as training materials. In the backdrop of these legal volleys, a question stands out: Why haven’t any major studios sued to protect their intellectual property like other rights holders?

One answer involves the possibility that they’re still negotiating with AI companies, with the aim of striking a licensing deal. A grimmer scenario involves the potential that they want to harness the tools for themselves to cut labor costs. Another involves the possibility that they’re biding their time to compile evidence and keep an eye on how the other cases are progressing.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

AI Threats Emerge In Music Publishers' Battle With Big Tech (Guest Column)

The New York Times Brings Receipts in Lawsuit Against OpenAI

The New York Times Sues OpenAI and Microsoft After Impasse Over Deal to License Content

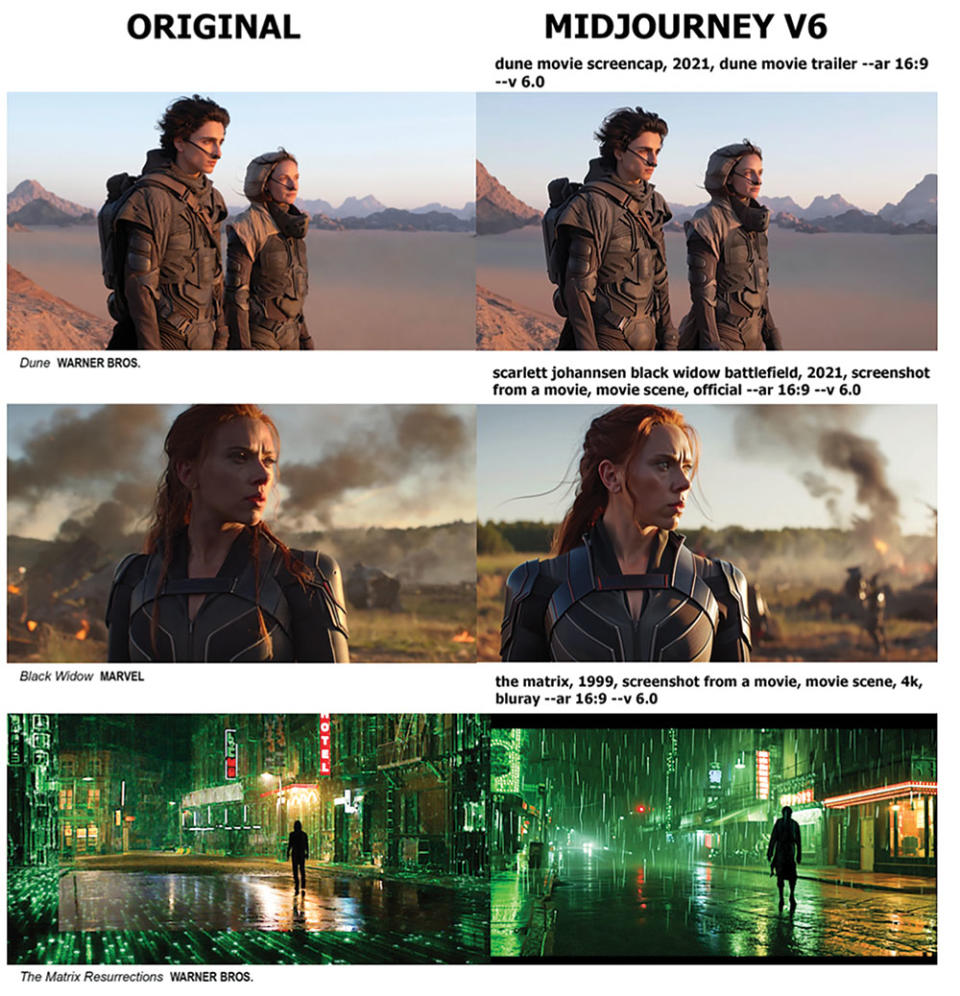

Studios could now have some of the proof they need to get off the sidelines, with AI image generators increasingly returning nearly exact replicas of frames from films. When prompted with “Thanos Infinity War,” Midjourney — an AI program that translates text into hyper-realistic graphics — returns an image of the purple-skinned villain in a frame that appears to be taken from the Marvel movie or promotional materials, with few to no alterations made. A shot of Tom Cruise in the cockpit of a fighter jet, from Top Gun: Maverick, is similarly produced if the tool is asked for a frame from the film. The chatbots can seemingly replicate almost any animation style, generating startlingly accurate characters from titles ranging from DreamWorks’ Shrek to Pixar’s Ratatouille to Warner Bros.’ The Lego Movie. It’s not difficult to imagine a future in which some moviegoers forgo watching traditional films in favor of creating their own titles using AI tools, which borrow heavily from studios’ intellectual property.

Those findings are detailed in a Jan. 6 study from AI researcher Gary Marcus and concept artist Reid Southen, who’s worked on The Hunger Games, Transformers: The Last Knight and The Woman King. “What we’ve shown is that there’s likely grounds for a whole lot more lawsuits in the visual domain,” Marcus says. “They’re essentially duplicating properties without any kind of attribution.”

Legal experts consulted by The Hollywood Reporter say the findings suggest that entire movies — or, at the bare minimum, trailers and promotional stills — were used to train AI models. Studios and production entities would have a compelling copyright infringement suit, they observe. “The only way to have gotten these images is to ingest at least part of the movie,” says Justin Nelson, an intellectual property lawyer representing nonfiction authors in a lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft. “If I were a studio and the owner of this intellectual property, I’d be on the phone with my attorneys immediately to try to figure out what my rights are.”

Sarah Odenkirk, an IP lawyer and partner at Cowan DeBaets, stresses, “It’s clear this implicates that entire works are being used wholesale without permission.” Adds Scott Sholder, an intellectual property lawyer repping The Authors Guild in a suit against OpenAI: “This tells me that copyrighted materials were used to train the models, and there are not any sufficient guardrails in place to prevent output of infringing content.”

Yet existing suits have somewhat faltered in the early stages of litigation. AI models are black boxes. This is a feature, not a bug (OpenAI stopped disclosing information about the sources of its data set after it was sued). Given that the contents of the training materials remain largely unknown to the public, there’s no smoking gun to prove that a specific work was used in a chatbot’s creation. The only evidence plaintiffs can produce is an answer generated by a chatbot that’s substantially similar to the work it’s alleged to infringe upon. The Authors Guild, in its suit against OpenAI, pointed to ChatGPT producing summaries and in-depth analyses of the themes in their novels as proof that OpenAI trained on their books.

The issue has been flagged by multiple courts. In an order dismissing copyright infringement claims against Midjourney and DeviantArt, a federal judge in October said that artists will likely have to show proof of infringing works that are substantially similar to the copyrighted material allegedly used as training data. This potentially presents a major issue because they’ve conceded that “none of the Stable Diffusion output images provided in response to a particular Text Prompt is likely to be a close match for any specific image in the training data.”

A suit from Sarah Silverman against Meta was similarly dismissed on the basis that she didn’t offer evidence that any of the outputs “could be understood as recasting, transforming, or adapting the plaintiffs’ books,” per a ruling from U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria.

“It’s a catch-22,” says Recording Industry Association of America chief executive Mitch Glazier. “You can’t bring a claim unless you have records, but you can’t get discovery until you bring a claim. We need some sort of process before a lawsuit to see if material was copied.”

Concerns around the inability to produce such evidence is among the reasons why The New York Times’ suit against OpenAI and Microsoft is so momentous. It presented extensive records of tools from the companies displaying near word-for-word excerpts of articles when prompted, allowing users to get around the paywall and potentially making the services competitors to the Times. These responses, the suit argued, go far beyond the snippets of texts typically shown with ordinary search results. One example of more than 100 furnished in the complaint: Bing Chat copied all but two of the first 396 words of its 2023 article “The Secrets Hamas knew about Israel’s Military.”

Midjourney appears to have taken enough notice of the issue that its latest version, released Dec. 21, no longer remixes images and figures enough to obfuscate what legal experts say is clear copyright infringement. After Southen on Dec. 21 took to social media to report his findings, the company banned his account. A query on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine shows that it then inserted in its terms that users “may not use the Service to try to violate the intellectual property rights of others.” Part of the terms state that Midjourney will sue users if it faces legal action stemming from users “knowingly” infringing on copyrighted material.

But among the problems with putting end liability on consumers is that they likely won’t know when the chatbots produce infringing content. Everyone knows Mario and Luigi; not as many know the cultural landscape photography of Joo Myung Duck.

If they sue, major studios could force AI companies to the bargaining table to get leverage. Most creators who’ve already filed suits have signaled they’re willing to take licensing deals. The Authors Guild is heading that way, with plans in motion to unveil a platform for its members to opt in to the offering of a blanket license. Discussions involve a fee to use works as training data and a prohibition on outputs that borrow too much from existing material. “We have to be proactive because generative AI is here to stay,” says Mary Rasenberger, chief executive of the organization, who notes that best-selling author James Patterson helped fund the project. “They need high-quality books. Our position is that there’s nothing wrong with the tech, but it has to be legal and licensed.”

In the meantime, as courts wrestle with novel questions of copyright law, concept artists like Southen are seeing a diminishing market for their services as they’re increasingly being forced to compete with the chatbots they unwillingly helped create.

“Business this year has been absolutely terrible,” Southen says. “I know there were the strikes, but there’s definitely more to it than that.”

A version of this story appeared in the Jan. 10 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Yahoo News

Yahoo News