'I was stunned when friends I'd met a few years earlier left me their beautiful house in the Welsh countryside'

Mike Parker’s home is more akin to a scene from a period drama. Floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, a separate sitting room to the lounge and an unruly yet characterful kitchen and dining area, it’s a delightful hodgepodge of eccentricity and wouldn’t be out of place in a museum.

“It’s funny you should say that, because the comedian Tudur Owen came and said it was like something from St Fagans,” Mike laughs proudly, while boiling water for tea on the stove in the cosy retreat in the countryside enough miles north of Machynlleth to render my mobile phone futile, reports WalesOnline.

“It needed lots of work when we took it on in terms of clearing a lot of stuff, but we deliberately haven’t really renovated it at all. Reg and George could have been considered hoarders I suppose. As you can see, we do have similar tendencies.”

Read more:

Read more:

The house - called Rhiw Goch, or Red Hill - was left to Mike and his partner Peredur (Preds) Tomos by friends Reg Mickisch and George Walton. With no close relatives, Reg and George left the four-bedroom old bed and breakfast and all its contents to Mike and Preds when they died weeks apart in 2011. Reg and George had met in 1949 in a London nightclub, got together in 1952 and were the first gay couple to receive a civil partnership in Powys in 2006, two months after such things became possible for gay people.

They’d moved to the area from Bournemouth in the early 70s having then lived most of their lives together somewhat discreetly up to 1967 when homosexuality was decriminalised. George had served in the Second World War and fought in France and Germany before returning to the south coast to pursue a career as a professional photographer.

Reg, a shop window dresser, later joined him, before they both moved to Wales to fulfil their wish to run their own live-in holiday accommodation in leafy bliss. In 1980 they paid £35,000 for a tired Rhiw Goch which took further investment to transform into a perfect getaway for visitors.

“I was stunned,” Mike, 57, said of finding out Reg had decided to change their will for them and instructed another neighbour and friend, Penny, to complete the paperwork. George had by then been gripped by the early stages of dementia. “I felt like I was on the edge of a precipice and that this whole life was opening up in front of me and all I could do was fall into it. I was thrilled and terrified.

“Looking back there was only Reg’s oblique comment about winter sunlight at Rhiw Goch and how much he knew I’d enjoy it that had given me pause for thought. The same for Preds - there had been just one fleeting moment of wonder when helping Reg in the garden when Reg told him to plant to his taste rather than theirs.”

In the months after Reg and George had died, while digging through the mountain of boxes of books which they’d amassed, Mike discovered a series of diaries penned by them both throughout their lives.

George in particular documented right down to the finest of details including his squabbles with the neighbours over a plum tree. Incidentally George’s final coherent sentence spoken to Mike before he died regarded his arguments with the neighbours decades earlier, adding: “But it’s all turned out rather well.” So fascinating were the entries that they spurred Mike on to write his own book about their lives which he called On the Red Hill.

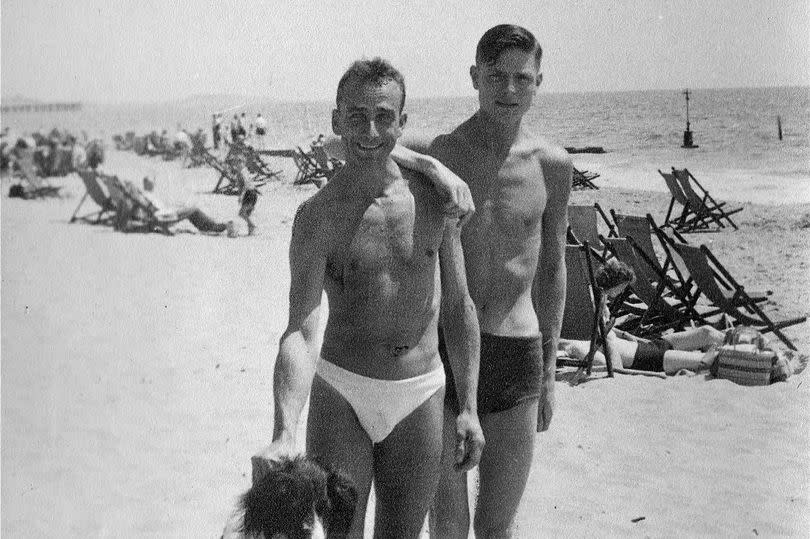

Navigating the stunning, busy garden to Mike’s office beside the house, he turns on his computer to show the many pictures George took of himself and Reg as they travelled Europe to more accepting destinations, teapot and deckchairs in tow. “They’re like something out of a catalogue,” Mike laughs. “Who on earth takes a teapot to a picnic? It’s a long way from a pasty at the garage isn’t it?”

We just get through all of the pictures before the broadband cuts out. “We can’t get a provider out here so we get it through 4G, but it’s so sketchy,” he sighs, before admitting it’s a small price to pay for inheriting the place. “It demands a different kind of life. I’ve done the city thing and I do miss it in parts, but this is my home and where I belong, totally.”

It doesn’t come as a huge surprise. Television only arrived in Rhiw Goch on the eve of the new millennium and as radio reception is so poor here - to this day the only reliable option is longwave - it was books which filled the lives of Reg and George and which have been so prevalent in Mike’s life too.

He has lost count of the books he’s written from this study but his story about the lives of Reg and George is still the one he gets asked about the most, while it has also been exhibited across Amgueddfa Cymru’s museums. “I get emails asking about them from all over the world all the time,” he says. “They’d both be blown away by that alone. But being on the wall of the National Museum of Wales, they’d be speechless. Reg would be rather embarrassed but thrilled. George would be delighted.”

Mike moved to the area from Kidderminster in the spring of 2000, meeting Preds three years later. They met Reg and George at a wedding locally and immediately had a fondness for the pair and would often drive up the hill to spend time with them.

“In our very first conversation Reg proudly described himself and George as pioneers,” Mike recalls of their first meeting. “And though I flinched at the inference rural Wales was some sort of Wild West dust bowl, I soon came to realise he was right, more so perhaps than he realised.

"Many of their English contemporaries moving to the area in the early 70s were straight young couples, mainly well heeled hippies. Not only were Reg and George gay, but they were respectable conservative gentlemen, lower middle class sons of London shopkeepers.

“There is that great phrase in Welsh: ‘A fo ben bid bont.’ Which means: ‘He who is a leader, let him be a bridge.’

"I think the characters which really matter in life are bridges between cultures, age groups, all sorts. And that’s what Reg and George were. They bridged many gaps and divides in their lives and they did it in very different ways.”

If there was any concern about two gay men moving to the village five decades ago it seemed to disappear pretty quickly. “Reg swiftly became a much-loved neighbour,” Mike says, retracing his chats with the locals.

“His kindness and curiosity, together with a rare talent for listening won round those quite startled by his and George's arrival. Even in the chauvinist early 70s rural Welsh speaking Wales was very much a matriarchal society, and the women gave Reg the nod and the men fell dutifully into line. Reg was a great listener and a naturally empathetic person intensely interested in people. They became very popular.

“I actually told Reg some time before he died that I wanted to write a book about him and George one day, which Reg batted away. I wanted to sit down and record Reg’s voice because he had such a way about him. But then he had a stroke and it heartbreakingly put the kibosh on that idea. I regret that now, not just for the fact I don’t have his words but because I can’t hear him. To conjure up the way Reg would have a conversation isn’t retrievable. It would go everywhere, like a rollercoaster. I’d leave after a few hours here and often have to go on a walk to clear my head.

“George was very different from Reg. He was very good at not getting emotional about things, very good at not letting things in. If there was any homophobia he wouldn’t have had any of it, just brushed it off completely. He was very self-contained to the point of probably being pathologically self-contained.”

It was through his photography where George was his most expressive. Pictures of their younger days among gay friends on Britain’s beaches were still treasured until their deaths. “It’s beautiful to see,” Mike says. “They were taken just after the war but they’re not all Homburg hats and raincoats.

They’re saying: ‘We are what we are and deal with it.’ Of course, the shame happens when you leave the beach and go back to normal life and every time you turn the telly on and buy a paper it’s in your face how terrible you are. I don’t think either of them ever got over that time. How could you?

“Reg was deeply affected for the rest of his life after his first boyfriend, Norman, was jailed for seven years for having sex with a man. It completely broke Reg. He never used a public toilet again for fear of entrapment and all that kind of thing which went on in loos. He was absolutely terrified of that right until the end of his life.”

Penny was devastated not to be invited to Reg and George’s civil partnership ceremony at Machynlleth Registry Office, which was only attended by Reg, George, Mike and Preds. George had become estranged from his family after the war and Reg was much the same.

When Penny asked Reg why she’d not been invited he replied: “Because you’re not one of us.” Neither of them had wanted to go through with the ceremony, but Penny persuaded them to for their own security - particularly for Reg who was ten years younger than George.

“From their perspective and the environment they lived in for so long, if you happen to be gay you certainly don’t go to the town hall and show it off,” Mike says. “They loved Penny, but it’s a sign of how Reg really compartmentalised his life.

"It was almost like he’d lock the gay away in a little box as a different section of his life. Even a state-sanctioned celebration of their lifelong love was something to be kept behind closed doors.

“Neither would talk about being gay. Even when this place was a B&B they never advertised themselves as gay-friendly. When you wanted to go away for the weekends when I was a young man you had to buy yourself a copy of the Gay Times to find the best places to stay as a gay person, but they never sought that market.”

In its 1980s heyday Rhiw Goch thrummed like a machine through the summer holidays. Reg cleaned, cooked and washed while George was front of house and totted up the figures. The enthusiasm in their visitors’ book discovered by Mike is heartfelt: "Out of this world," "Best food since I’ve been in GB," "Stayed the second time and will come again and again," "An island of peace and kindness," "Cartrefol dros ben (extremely homely)."

That warmth wasn’t always reciprocated by George, who’d often cantankerously write of guests in his diary, documenting how he’d given one a ferocious dressing down for leaving a slither of bacon on their plate at breakfast. He also told of how he gave a telling off to a party of Australians for taking too many baths, after which he introduced a 15p bath surcharge. Reg became adept at smoothing over the feathers ruffled by George’s occasionally abrupt behaviour.

“When you read about the squabbles George had it is hilarious but also gives a real insight into his state of mind and how utterly obsessed he was,” Mike laughs. “One particular dispute with a neighbour clearly took over his life. It is brilliant that he recorded all of it. I suppose now people will have these trails of social media posts. Biographers in 30 years time are going to be sifting through Twitter feeds, God help them.”

Sign up now for the latest news on the North Wales Live Whatsapp community

Sometimes George would write footnotes into the entries, almost as if he was writing for an audience in the hope it’d be picked up after he’d gone. “I do wonder whether he knew his mind was slipping and they were for him to jog his own memory, or whether he wanted it to be written about and looked back on in future,” Mike says.

Mike and Preds had some grief, much of it with an undercurrent of jealousy, when they inherited the house. “I soon learned I was allowed no reservations about it (inheriting the house) at all, because people could not bear to hear them.

"My doubts and fears of change, of being uprooted from the place I’d chosen, of the two of us being forced into intense and isolated co-dependence, became dark shards of ingratitude that I had no way of processing. If I tried I was sometimes stopped dead by friends who’d snap: ‘For God’s sake, it’s all right for you, you’ve inherited a bloody house.’ It was always the trump card.”

Much of that has now gone away, or they choose to ignore it. What hasn’t left them is their unshakable identity as Reg and George’s second coming. “The ease with which we’ve absorbed their friends and neighbours is seamless, but slightly odd too,” Mike says.

“Are we so much their sequel that affection has just seeped effortlessly from their regime to ours? To some of the local ladies of a certain age, the ones who squeeze your thigh after a large gin and tell you how much they ‘love the gays’, I wonder whether we are distinguishable individually at all.

“I think there is something in that which is rather nice. The parish gays. Everybody in rural communities fulfils a role, whether they would like to or not. You become a cliche of what you are. We’re not the only homosexuals around here by a long chalk, there’s been an influx of queer folk in the area.

“The habitat of the queer person is still assumed to be principally urban, although that’s changing. Yesterday we had some American students visiting who were blown away by the whole queer rural thing and the diversity within Wales’ green spaces.

"When I first moved here people told me I’d die a lonely man. I knew they were wrong, because I genuinely believed and do believe Wales has something really special about it.

"It’s a tolerant and accepting country. Maybe that’s something to do with being a small nation. Take the Welsh language and the revival we’re seeing there.

"To me there is a sort of mutual understanding between Welshness and a queerness which should be embraced.”

Last month Machynlleth hosted its first ever pride festival. Shops were dressed in LGBT+ colours, there was a rainbow marquee, a kids’ crafts area and live music. Mike performed readings of On the Red Hill in the town library.

“One of the passages, which is one of my favourites, was about how when George had become very ill and housebound, Reg would take himself off into the town by taxi or bus and spend one day a week in Mach. He’d just float around the place and chat away to old and new friends. It gave him enough. Reg thrived on people and conversation.

What would Reg and George have thought of Mach Pride? “I’m not sure. I don't think they'd have gone. Maybe George would have had a mooch while pretending to be shopping.

"To be honest it seemed extraordinary to me, to think pride had come here. I think it’s marvellous, especially when you think of what that would mean for kids growing up here. Ever so many of the shops had made the effort to do lovely decorations.”

Nine days after he was moved into the same nursing home as George Reg died following complications from bronchial pneumonia. “We raced over there and sat by his bed holding a hand each and talking to him,” Mike recalls. “I nipped out to make a call and when I returned he’d gone."

George was in the dementia unit on the floor below. For well over a year he and Reg had been in different locations, yet they’d ended up for those last nine days only feet apart. It seemed cruel they never got to see each other, but perhaps proximity was enough.

“Five weeks later Preds was driving back from Wrexham for a day at the Eisteddfod. Shortly after passing Welshpool he was walloped by severe stomach cramps and forced to turn back. As the cramps eased a small voice told him to visit the nursing home. At the moment Preds walked into his room George took his last breath.”

In one entry, when Reg is still at Rhiw Goch but George has been moved, Reg writes: “I do miss George very much. He was my life. I dare say I love to [sic] much. Oh well.” In another, he writes: “I’m told I can’t look after him. I’m not much cop to him. Feel I’ve let him down.” Mike remembers how one of the final things to leave George’s consciousness was his love for Reg. “Towards the end of Reg’s life when he was taken to the local rehab hospital, George - who was already there - saw him across the foyer and burst out, ‘There’s Reg, I love Reg.’ Even the nursing staff, inured to daily doses of heartbreak, looked teary

“I really wanted to write something timeless about them that would last and I’m so glad I’m still reading about them at events like pride, because, particularly in terms of progress, I wanted to write something which showed what progress has meant for real people. Their lives to me are a sort of marker really and a lesson in how we can’t take things for granted and must keep pushing on.”

Does he have arguments with the neighbours? “No, luckily,” he laughs. “We’ve got some great neighbours and they look out for us as we do for them.

"What I do remind myself of is that much of the land which surrounds us here has been in the same families for generations and in some cases hundreds of years. I’m very conscious of that. I’m conscious I’m a footnote, if that, in the context of this vast, beautiful landscape.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News