Tavares Strachan review – encyclopaedic art that sizzles with life

‘You belong here,” reads the neon sign high on one of the Hayward Gallery’s exterior walls, in a curving handwritten script. But where are we and what does belonging mean? That’s what Bahamian artist Tavares Strachan asks in There Is Light Somewhere, which fills the building. Origins and arrivals, disappearances and sudden returns have a big part to play in Strachan’s art.

Along the way, the artist has walked to the north pole, following Black polar explorer Matthew Henson, and taken a block of arctic ice back to the Bahamas. He has trained as an astronaut in Russia and blasted a sugarcane-fuelled rocket into the stratosphere, as part of a programme to interest young Bahamians in science and technology, and to further whatever dreams they have of escape. Referencing sports and reggae, untold lives, the writings of James Baldwin and Black astronaut Robert Henry Lawrence Jr, Strachan’s art is always encyclopaedic, engrossing, disconcerting and engaging. Neon figures sizzle with life. Writing flares on a black wall. Highly crafted sculptures rise from living fields of rice and sounds fill the air.

In a hut thatched with grass – inspired by the structures where the ruling kabakas or kings have been crowned in Uganda’s Kingdom of Buganda since the 14th century – DJ decks sit in place of the monarch. Old scraps of sheet music dangle from the walls and roof – Hit the Road Jack, Goodbye Pork Pie Hat and Johnny B Goode among them – and from the speakers built into the decks comes a collage of whispers and cries, rumbling bass and dub reverb, snatches of song and call-outs for Haile Selassie and the enthusiastic voice of American astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson. Lights pulse from the thatch. It is like history’s jukebox in here.

While I’m looking and tapping my feet, a couple wander in and start singing a soulful a cappella duet. The pair have been dogging my path since I arrived. First they were having a row in the foyer, then the guy had the temerity to walk straight up to me with some dumb-ass non sequitur trick question just as I’m getting into full critic mode. As I’m about to call security I noticed he was carrying a small, pocket version of Strachan’s Encyclopedia of Invisibility, a vast tome that sits in a vitrine up on the Hayward’s mezzanine floor, and had started riffling the pages and singing out entries. Next time I saw the bloke he was sobbing – very loudly – in front of a neon version of a text by Baldwin, whose writing gets to some people that way. Good or bad, I can handle most art. It is the people that get to me. It turns out they are part of the show, another level of disruption and intrigue, another mental trap door to fall through.

Strachan once said to me that he wanted to put the audience in the driver’s seat, and to hand them the keys. He never mentioned how many hitchhikers we’d pick up on the way or the swerves our route might take.

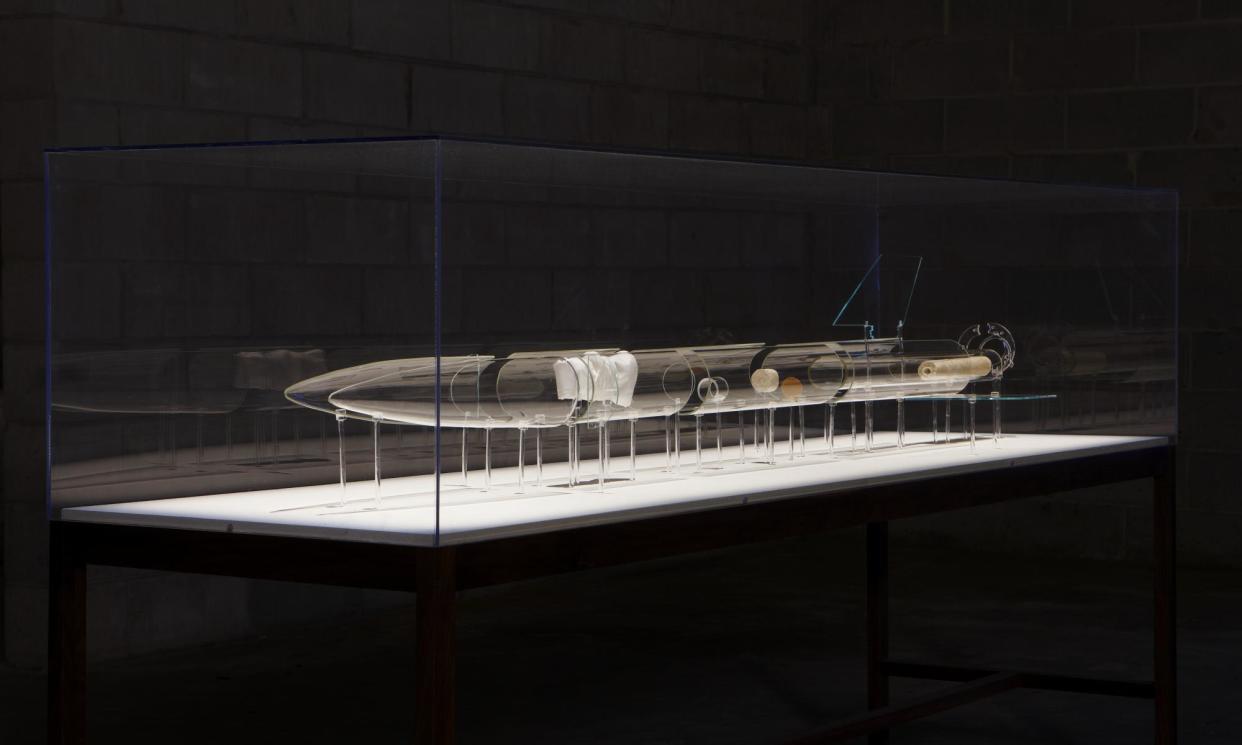

It’s freighted with history, peopled by the overlooked and the flawed: Nobel prize-winning poet Derek Walcott; gospel and blues guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe; and American gay rights activist and self-proclaimed drag queen Marsha P Johnson; Black artists and activists and explorers – all commemorated in sculptures and complex images, in neon and in Pyrex glass sculptures that hover uncertainly as you move around them, appearing and disappearing in the tanks of water that contain them, or memorialised in portrait busts, half hidden behind African and Oceanic masks, or disguised by patterning, they rear up, demanding recognition.

Murdered South African anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko’s head bursts from a bust of Septimius Severus, African Emperor of Rome from AD193 to 211, and the crowned head of Nina Simone folds open to reveal the Queen of Sheba within. Rosetta Tharpe’s ceramic head emerges from a pot. Another sits on her head, like a crown, and on top of that squats a pigeon. There’s something loving about these plays with convention.

A large-scale model of a reconditioned first world war collier, the Yarmouth, floats on the black waters of a pool that floods the Hayward’s sculpture deck, overlooking Waterloo Bridge. A trail of bubbles streams along its flank, as though the ship, bought by Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey as the flagship of a fleet called the Black Star Line, with the intention of trading between the US, the Caribbean and Africa, and of facilitating travel by African Americans as part of Garvey’s contribution to the Back-to-Africa movement, were making its way down the estuary towards the sea. This is but one of the astonishments, history lessons and games of space and time in only the artist’s second solo outing in the UK.

A huge, patinated bronze bust of Garvey also sits outside the Hayward’s entrance, while inside other works from the same series, Ruin of a Giant, greet us in the gallery. One depicts Jamaican sound engineer King Tubby, another American abolitionist and activist Harriet Tubman. Deep fissures scar the surfaces of these sculptures, as if they had been pulled down, buried for centuries and disinterred. Within these artificial cracks run lines of poetry. You have to get up close and squint to see them. Like much in Strachan’s art, there’s a lot of discovering to be done. King Tubby’s head looks askance from his plinth. Much more than a local sound engineer, his influence on the art of remixing and on dance music continues to reverberate, escaping the insularity of genre and place.

This is but one of the backstories Strachan’s art attempts to tell, whether it is Queen Elizabeth II’s meeting with Haile Selassie (when the Queen reputedly bowed to the Emperor of Ethiopia, as he was of higher rank) or Garvey’s doomed maritime enterprise, after being infiltrated and sabotaged by J Edgar Hoover’s Bureau of Investigation (forerunner of the FBI). Although sometimes overdone and sometimes overwrought, Strachan’s art attempts both humour and seriousness. The two are not incompatible. The disruptions keep us alive to his glorious, crazy game.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News