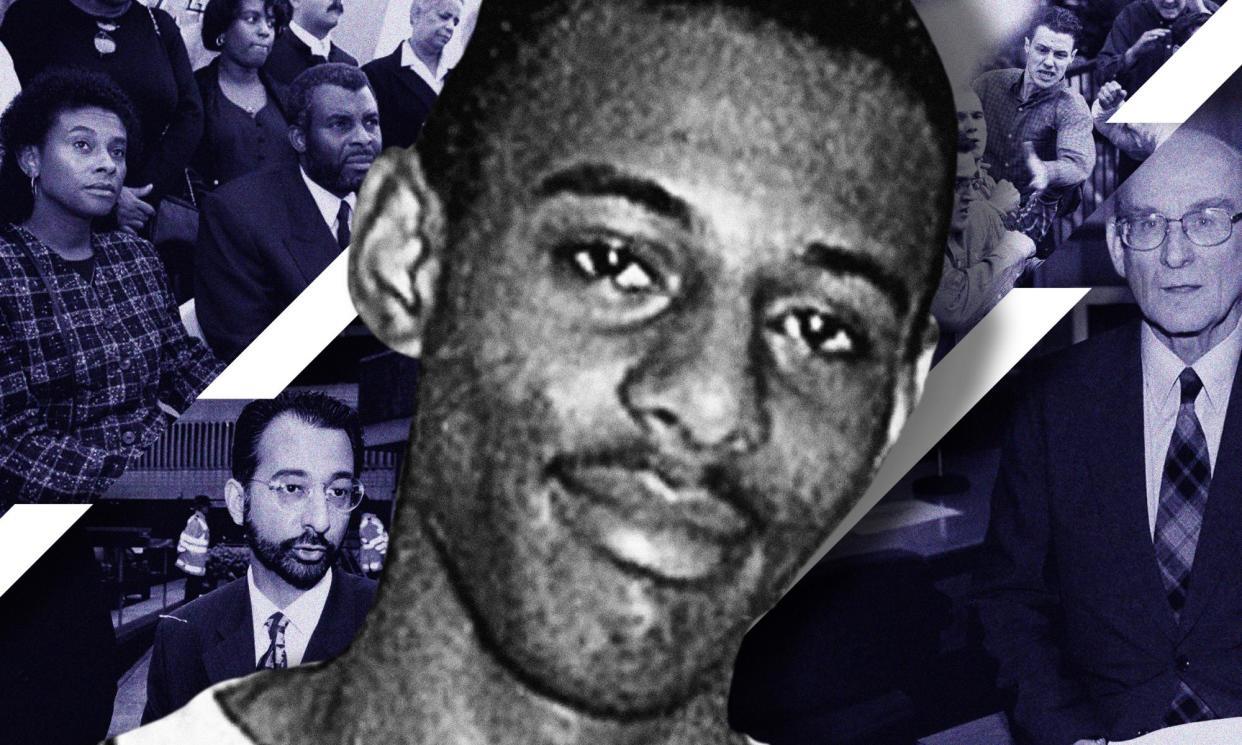

Thirty years after Stephen’s murder, 25 years after the official inquiry, why won’t the Met change?

Where do we find ourselves, a quarter of a century on from Sir William Macpherson’s historic inquiry? It’s a difficult question to answer. Today, institutional racism in the police feels just as urgent as it did back then. It’s hard not to think that we haven’t covered as much ground as we should have by now – tomorrow marks 25 years since the report was published.

People tend to forget what led to the inquiry in the first place. In 1993, my son Stephen was brutally stabbed to death in a racially motivated killing. The investigation into his death was marred by “professional incompetence, institutional racism and a failure of leadership”, the Macpherson report found.

I often think back to when Stephen died, and my first meeting with police. I was sitting in a room with senior officers, who told me: “Stephen’s killers were just thugs.” They weren’t thugs: they were murderers. I remember telling them: “Do not make the same mistakes you made with all the others who have been murdered. His name will not be another statistic. You will remember his name.”

I couldn’t have known then where that statement would take me. I just knew that I would not let people forget about him. He was an ordinary man going about his business – and those people in a position of power ignored our cries.

Eventually, almost 20 years after his death, two of Stephen’s killers were jailed. But Stephen wasn’t the first young black man to be failed. The police had an opportunity to make changes decades before his death. Perhaps if they had, he would still be with us.

I know that life goes on. But for families like mine, who have felt the direct consequences of police failings – failings that continue despite our tragedy – how do you ask them to move on?

It’s soul-destroying to know what could have been – that those with the power to do so didn’t make the changes that would have saved families from so much suffering. I often think what could have happened had the police done their job before Stephen was killed. I think about having my son here with me. I wonder what we would be doing together – what our lives would look like.

It’s sickening to feel that the same issues are still happening today. Every morning since Stephen’s death, whether I’ve got an alarm set or not, I get up fighting. Because no one is giving me anything, and the situation facing black communities will not get better on its own. The inquiry didn’t happen because the Labour government pushed for it – I pushed them to do so. I had to dig my heels in and remind everyone that my son was important. Just as all the other young black men and boys were important.

When Macpherson delivered his report, he had to adjust his starting position. Listening to all the evidence in front of him, he couldn’t avoid coming to the conclusion that there was institutional racism within the Metropolitan police. And yet, after the report by Louise Casey last year, which again identified a culture of “institutional racism” in the Met, the force’s commissioner, Sir Mark Rowley, refused to accept that it was institutionally biased. If you don’t accept what is wrong, how do you change it?

I ask myself why the police are so resistant to change. My only conclusion is that they are arrogant. They believe only in themselves, and don’t think they need to change. Occasionally I hear that a police officer has been suspended, but it’s not enough. So much more needs to be done. I’ve spoken to the commissioner, and one of the things I told him is that only when the community can see and experience change can the police truly say they are making changes.

Recruitment and retention of black officers within the police was one of the big areas that Macpherson highlighted for improvement. And it is a crucial issue today. In my experience, many senior officers are capable of understanding the issues involving policing of the black community. But the lower ranks don’t. What’s more, black officers are still more likely to be disciplined, and are less likely to be promoted than their white counterparts.

Representation in the force has a direct impact on the communities that are being policed. When the Macpherson report was published, young black men did not feel protected by the law. Lots of them decided they had to protect themselves, and started carrying knives. This is how I think our knife crime epidemic got so out of control. Instead of tackling it when it first started, the police set up Operation Trident – and helped to popularise the idea of “black-on-black” crime. These murders were investigated completely differently to white murders. The police just didn’t care. And I still think they don’t care.

Our education system also needs urgent reform. Twenty-five years after Macpherson suggested reforming our national curriculum, black Britons still don’t learn about their history in British society. Unless this is changed, they will always grow up feeling that they are seen as second-class citizens. When the Windrush scandal happened, people needed to know that those from the Caribbean were asked to come here. That should have been part of our history lessons.

In Britain today, when some people say “black lives don’t matter”, I believe that to be true, which is sad. Too many mothers have lost sons. Are we going to carry on talking about this for the next 25 years? Change must come.

Today I remember Stephen in different ways. I think about different stages of his life. I remember little things he would say to me, like: “Mum, you know what your problem is? You care too much.” After he died, people would tell me how they knew him and how they met him – I hold on to those memories. That sort of comfort is really good to have. So many people saw the goodness in him. That’s what I would like other young people to see when they look at Stephen’s face – that they have goodness in them, too.

As told to Lucy Pasha-Robinson

Lady Lawrence of Clarendon is a life peer and a social justice campaigner

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News