‘A Thousand and One’ Director on Hollywood’s Diversity Gains: “Progress Is Happening, and This Is a Sign of It”

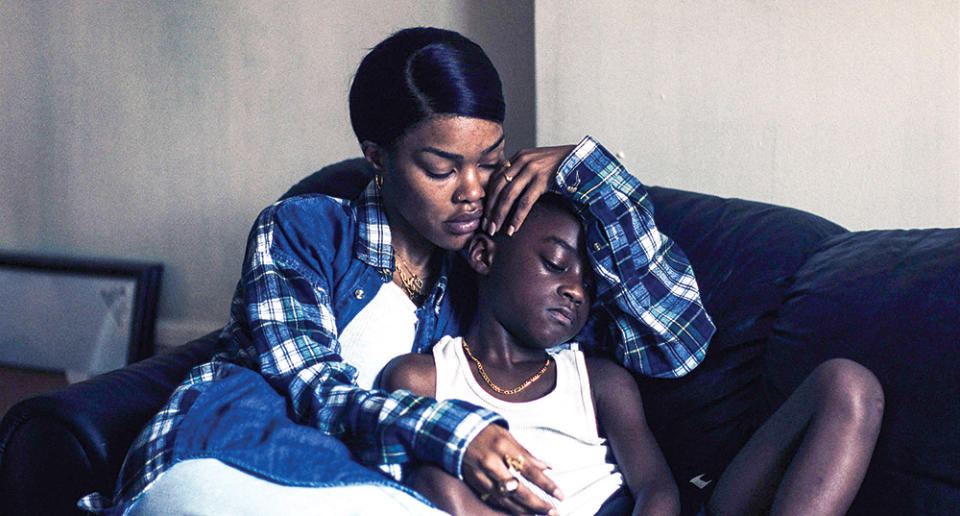

From the first moments of A.V. Rockwell’s debut feature, A Thousand and One, the audience is in the company of Teyana Taylor’s vivid portrayal of Inez, a woman in 1994 Harlem. She’s just out of Rikers and on a mission to rescue her son, Terry, out of the foster care system. As Terry grows older, the viewer follows their loving, messy relationship in a changing city. After winning the 2023 Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, A Thousand and One has continued to rack up accolades for Taylor and Rockwell, who now finds herself nominated for first-time feature film at the DGA Awards. She recently talked to THR about the inception of her indelible central character and her portrait of New York.

What is the origin of Inez?

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Killer Mike Talks Grammys Arrest on 'The View': "All of My Heroes Have Been in Handcuffs"

Feinberg Snapshot: How the Grammys and Other Recent Events Are Impacting the Oscar Race

It was really about creating a character that I wanted to see, especially in the way that she was representing moms of color. For me, she was a fantasy of somebody who is so fearless and in control of their own destiny, or very determined to be, anyway — especially when you think about movies depicting our stories, like the white savior narrative, somebody else coming along to save the day. It was really important for me, from the very beginning, to make sure that she was this woman who was such a force of nature and such an homage to all the women that I knew in real life that were very committed to being a champion of the people around them. I wanted her to be imperfect because I think the best characters are. I’m really invested in stories about redemption. It’s important to make sure that we’re not suggesting, as storytellers, that you need to be a perfect human being in order to be worthy of love and affection.

Was Teyana always your first choice for Inez?

I was looking for a performer who felt truthful, not only in a way that she could portray the layers of this woman, but also in how she represented New York. I didn’t want it to be performative because not everybody can portray an experience like this that’s not their own, particularly that of just this urban, everyday woman roaming around New York City. I didn’t want anything to come up false. We looked at a lot of names of some of the most exciting women working in Hollywood now, but also, I was on social media looking for fresh faces — there was a rapper, whom I won’t name, whom I was looking at. It really wasn’t until I saw Teyana’s tape that it became so obvious that she was the right combination. She had enough experience to bring what I was looking for in a performer, but she also knows this woman in real life. She just had the right level of a real empathy and connection.

The depiction of the Giuliani era in the film’s beginning is so evocative. But could you also talk about how the dawn of the Bloomberg era is also evocative for you in this way?

In the Giuliani era, especially at the beginning of the film, I wanted to emphasize the vibrance of what New York City was on a number of levels. You feel it in the colors, you feel it in the textures and the voices, how much the city was a character. Even though the city was coming out of a very tough period in its history, it was a city that was considered less desirable but at the same time more inviting. But obviously, when Giuliani came in and he cleaned it up and made all of these changes, the city that he was trying to shape in a way that became more inviting, I think, ironically, feels even less so. At the turn of the century, and as Bloomberg takes it on, it is less inviting, it’s less colorful. It’s more glass, more steel and less accessible for people of various socioeconomic backgrounds.

There’s been a lot of hoopla since the Oscar noms came out about the Greta Gerwig snub for best director. Looking at your category at the DGA Awards, Cord Jefferson is the only male nominee, and, on a whole, it looks a lot more diverse than what the Academy came up with. What is your take on the fact that you’re in a category with primarily female directors, a number of directors of color, and yet it still feels like there’s a hurdle when it comes to the bigger awards shows?

Progress is happening, and this is a sign of it. But it’s slow and it’s complicated. Sometimes it feels like we’re taking two steps forward and then we take five steps back. And sometimes that’s at the same time, which is ironic because even in the context of my film, if you think about it, that’s really how my movie ends. Inez succeeds in breaking the cycle, at the same time as they still have lost against repeated cycles. Yet, again, their family was on the verge of being broken apart — in this case, through gentrification, which is another new obstacle for communities of color. But at the same time, she still succeeded. She knows for a fact that [Terry is] going to have a better life than she and Lucky [her boyfriend turned husband, played by Will Catlett] were ever afforded. I think that, even in this moment, in the way that you’re acknowledging the life that I have as a filmmaker coming up in this industry, it’s the same thing. I see a lot of nuance and a lot of red tape that can explain why our stories are still not as recognized or our work is still not as recognized. But at the same time, there is change. I’m happy for the progress that is happening, but I’m not settled in it because I know that we have to keep putting pressure on people.

This story first appeared in the Feb. 7 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Yahoo News

Yahoo News