Tiggy Walker: ‘We’re openly confronting Johnnie’s death – I’m already selling his clothes on Vinted’

Sunk into an armchair, his wife Tiggy hovering protectively nearby, Johnnie Walker is showing me a painting of Brighton seafront that he received this week from a loyal listener who, in 2021, lost his teenage son. On the back the listener has written to reassure Johnnie that death is never the end, that the love never stops.

“So many people who love Johnnie have been in touch,” says Tiggy, a cheerily indomitable former television commercials producer to whom Johnnie has been married for more than 20 years. “Listeners write in even though they don’t know our address. They just put ‘Johnnie Walker, DJ, Dorset’ on the envelope, and somehow it gets to us. Ray Davies, Peter Kay, even Elton John rang the other day.”

Elton? “Yes, he’s a very thoughtful man,” says Johnnie. “I helped him out at the start of his career, gave him a lot of radio play. He wanted me to know he had never forgotten that.”

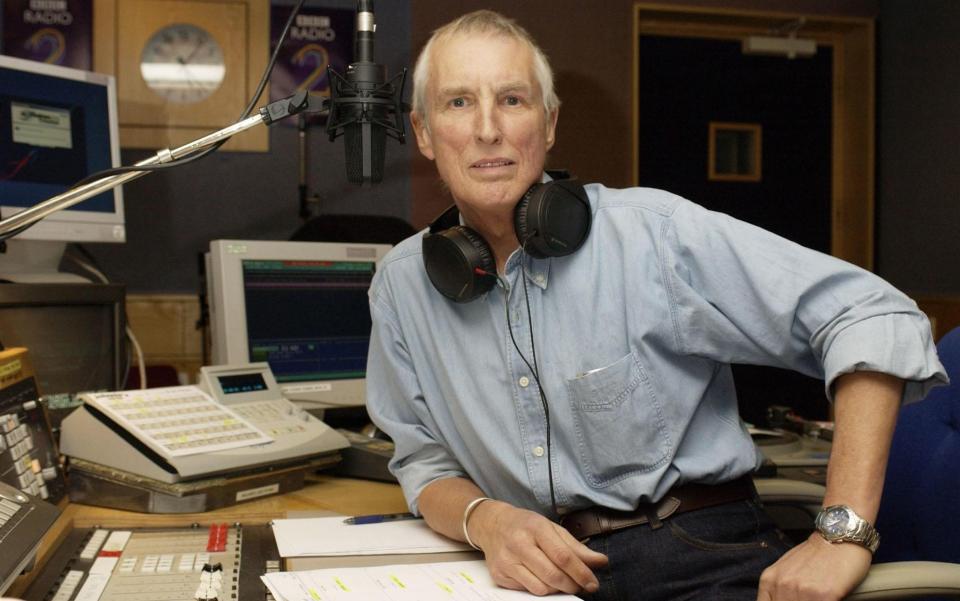

Ever since Tiggy, 63, appeared on Jeremy Vine’s radio show on Monday to reveal that beloved fellow Radio 2 DJ Johnnie, 79, has incurable idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the phone has not stopped ringing, or perhaps more accurately, pinging. During that interview, the couple also said that Johnnie, whose Sunday broadcast Sounds of the 70s has been delighting around two million listeners a week for nearly 15 years, is now wheelchair bound, dependent on an oxygen machine and has been told by his doctor that he could die at any moment: the initial prognosis was two to five years; the five-year mark is this August.

On Monday the couple put out a podcast on BBC Sounds in which they discuss Johnnie’s illness with affecting candour. It quickly made the top three on the service’s on-demand list. On Sunday afternoon Johnnie will make reference to his illness for the first time on his radio show, which he has broadcast throughout from home. What song has he chosen to begin with? “Smokey Robinson’s Tears of a Clown. But not for any particular reason except that it’s a great song. I’m not yet at the stage where I’ve become sentimental about my choice of records. When I realise that I’m broadcasting my very last few shows, it might happen then.”

We are speaking in the Dorset home into which the couple moved three years ago after Tiggy realised the damp in their adored Georgian farmhouse was exacerbating Johnnie’s illness. It’s a new-build, which Tiggy hates, but it’s also single storey, which allows Johnnie to disappear into his “den” as he calls his recording studio, whenever he feels like listening to some music: John Prine, Jackson Browne, his beloved Bruce Springsteen. He spends most of the day, though, in the main room, whose floor-to-ceiling windows look out onto fields.

The walls are adorned with paintings, a Springsteen box set lies on the table, and if it weren’t for the percolating hum of the oxygen machine, and Johnnie’s frequent shortness of breath, you might not think he was seriously ill at all. “I panic occasionally when I can’t breathe. But the good thing is I’m not in any pain.” He gives a wry smile. “I feel like an old man in a pub talking about what’s wrong with me. I’m not at ease talking about it really.” In person he has the same unstarry demeanour that has made him such a comforting presence on the radio for so many years. “The spotlight doesn’t seek me out,” he says. “I don’t like fuss. I’m a modest man.”

The couple, who have no children (although Johnnie has a son and daughter from his previous marriage to Frances Kum, whom he divorced in 2000), have only chosen to speak out about Johnnie’s illness to bring attention to Carers Week, which concludes on Sunday. They have been co-patrons of the charity Carers UK for more than a decade, having endured a marriage that has experienced ecstatic highs but also awful suffering.

The pair met in 2001 and married the following year. But during their honeymoon in Kerala, India, Johnnie became terribly ill with what turned out to be non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Almost overnight Tiggy went from giddy new bride to full-time carer. Johnnie recovered and went back to work in 2004. Then, in 2013, Tiggy was diagnosed with stage-four breast cancer, from which she has now recovered.

It was Johnnie’s turn to roll up his sleeves. “She wasn’t a very good patient,” he grins. “Because, of course, she wasn’t in control. And Tiggy loves to be in control.”

“I was fat and bloated on steroids,” objects Tiggy. “The chemo was so bad it felt like dying. But you were also awful when you had chemo. It completely changed your personality. I once cooked you pea soup and you screamed at me: ‘I don’t f---ing want pea soup!’ We were not long married, I was terribly insecure and like a terrified rabbit. I was no longer sure who I had married. After you went back to work I sank into a dreadful depression.”

Carers UK estimates that more than 10 million people have been or are caring for a loved one, saving the NHS around £162 billion a year: the equivalent, in effect, says the charity, of a second NHS, which receives about £164 billion each year in funding in England. The Government pays carers £81.90 a week, but only if they earn less than £150 a week – although the job is so demanding six out of seven carers give up their jobs entirely.

“The whole system is out of date,” says Tiggy, who quit her highly successful, well-paid career to look after Johnnie when he first became ill; she has since carved out a part-time career as Johnnie’s manager, has a column on the local paper and is currently developing a film based on Naomi Jacob’s 1964 novel Antonia. “The way healthcare is going, [the NHS] doesn’t want to take people who are ill into hospitals or homes or hospices. They want these people to be cared for at home. The NHS bring you the equipment – the bath lifts, the wheelchairs, the oxygen machines. But it does depend on one person to do it all – a spouse, a mother, a daughter. I’m not of the belief that the government should support everyone in every situation. I don’t believe in victim culture, no one ever said life is fair. But there are a lot of people who are suffering. The NHS and the government need to be much more aware of the impact of all this on the carer.”

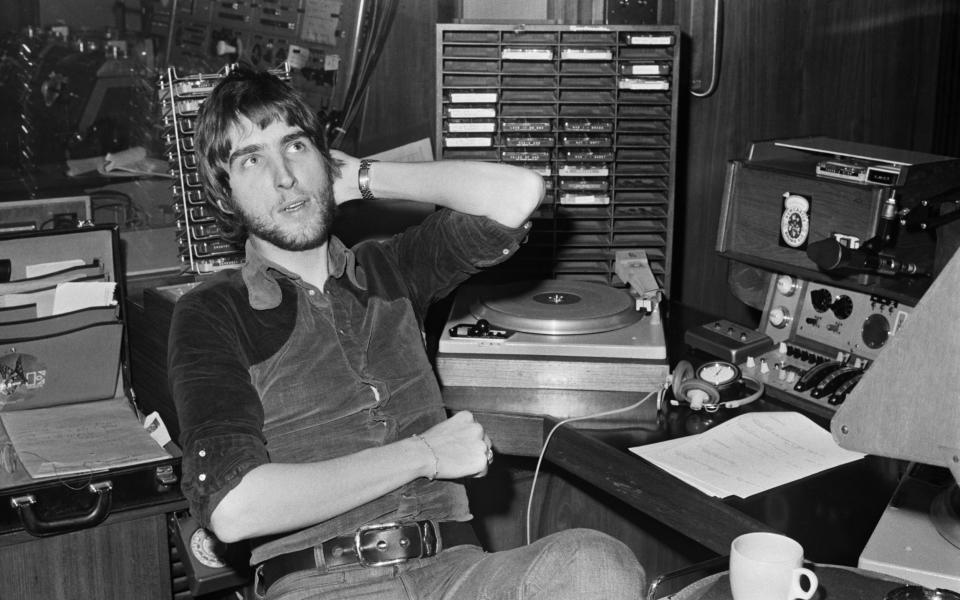

Tiggy and Johnnie fell in love pretty much the day they met. She was the no-nonsense, glamorous career woman with her own production company, he was the laid-back DJ who had begun his career with Radio Caroline and who by 2001 had made his Radio 2 drivetime show the most listened to drivetime show in the UK. Yet when Johnnie developed cancer she felt terribly alone.

“He was still in his 50s, with everything to live for, he hated being ill. I’m of the generation where you just get on with it, but I also felt terribly ignored. There was no recognition back then of carers at all.” This time she has plenty of support – although Johnnie’s son Sam, who runs a mobile phone business, lives in Australia, his daughter Beth, a website designer, lives an hour away and comes over frequently to help. The couple has a large network of friends, including Tiggy’s brother, a chef, who often comes over and cooks dinner.

A carer comes in on Wednesdays – and Tiggy sometimes uses the chance to nip up to London to catch a matinee. The two maintain a semblance of normality as much as possible, eating supper together every night and enjoying a glass of wine. “It’s a very tender time for us,” she says. “It’s like our own mini lockdown.”

Yet she is the first to admit how difficult and inescapable the job can be. “To be honest, Johnnie could live for another six months and, on one level, the thought terrifies me. I am utterly exhausted.” Inevitably, the dynamic of helping each other through potentially terminal illness has recalibrated their relationship. “You meet and fall in love and you are equals,” says Tiggy. “Then when Johnnie went to hospital after our honeymoon, it was as though I had become a mother and Johnnie was the child, Because of how the illness had affected him, some of the caring I had to do was repulsive.”

“That’s a bit personal,” chips in Johnnie. “I’m not sure I want to talk about that. But it’s true, this illness is a bit of a downer on the romance side of things.” The couple now sleep in separate bedrooms. “We used to travel an awful lot, go to parties. Now, we can’t even go to the pub.”

Yet if they have lost the ability to do the sort of things many couples take for granted, there is a lot they have gained. They are able to talk freely about their love for one another, but also confront with astonishing frankness the reality of what is about to happen, and what will follow when it does. Tiggy is invigorated by the plans she has made for her life after Johnnie dies. “When I married Johnnie, his career definitely took priority. There was even an infuriating perception among some BBC producers that I was lucky to be Johnnie’s wife. Now as I move into my 60s and Antonia is coming together, I feel I’m coming back into my power. I can’t imagine what it will be like with Johnnie not being here, but I will also be in charge of my life again. A bit of me is excited about that.”

She has already contacted an estate agent about the hated bungalow – “the brochures are ready to go” – and has her eye on a cottage a couple of miles down the road. She is adamant, though, she won’t have another relationship. “There will be no one after Johnnie. Because how could anyone follow him?”

Johnnie is equally pragmatic. “I need to die quickly so that she can get on and make her film,” he jokes. Sam came over from Australia in November and Johnnie has accepted he is unlikely to see him again. He has moved all his streaming accounts into Tiggy’s name and paid off the credit cards. The couple have even started putting some of Johnnie’s clothes on the online secondhand marketplace Vinted. “We have a right laugh about it,” says Tiggy. “Some people have got absolute bargains – the other day we sold a lovely Richard James dinner suit for a song.”

Johnnie is mulling over whether to sell his vinyl collection to put behind the bar for the wake. Have they finalised the funeral? “Yes, but I don’t think we want to reveal the details. We need to keep a showbiz element of surprise. Although Tiggy has said that after the service she wants the hearse to go up the high street to the crematorium blasting out Springsteen’s Born to Run.”

“You’ll be on your own then, Johnnie,” she reminds him. “I’ll be with our guests. I don’t believe in holding your hand until the very last minute.”

Johnnie has been determined to continue broadcasting his radio show throughout his illness. “We need the money,” he quips, but he is only half joking: Tiggy points out that only the big names at the BBC get paid huge salaries. Later, in the car on the way back to the station, she says that she thinks the BBC has always underestimated Johnnie, that it has never fully appreciated his talents, although she is quick to point out they have been brilliantly supportive since he became ill.

When he was first diagnosed, Johnnie was anxious that listeners would realise there was something wrong with his breathing, even though his pauses for breath were carefully edited out. But it was always important to him to carry on. “For many people, Sounds of the 70s is part of their Sunday afternoon. As long as I can keep doing the show I will. It gives me a purpose. If I stopped doing it I’d probably die a lot sooner. Anyway, when you play records you are bringing back memories for people as well as playing records that they love.” What song brings back memories of Tiggy? “It would have to be Cyndi Lauper’s Time After Time. She had Terry Wogan play it for me when I was first ill with cancer. ‘If you fall I will catch you, I will be waiting, time after time’. That sums it all up, really.”

Both believe in the right to assisted dying, although Johnnie has a few more reservations than Tiggy. It is not, though, an option for him. “I’ve even said, if I get a chest infection, which would kill me in two or three days, I don’t want to go to hospital. I want to remain at home.” He is hoping he might die in his sleep. Pulmonary fibrosis usually manifests as a gradual then very quick decline and no one can say how much time he has left. “I’m certainly spending more time in bed. I’ve got a hospital bed arriving on Monday, which will help with when I start to struggle with sitting up.”

Is he prepared for what is about to happen? “Yes. I’m not afraid. I believe in life after death. I know I’ll be able to look down on Tiggy. She’ll go through loss and sorrow but she will also be free.” What will he miss? “A decent glass of red. But I don’t think I will miss anything else. The body passes from the physical realm to the spiritual realm. That said, she has the most beautiful blue eyes.”

And Tiggy? “His incredible sense of mischief.”

Until then, it’s a case of day by day. “I never quite understand what Tiggy means when she says I’m a fighter. I’m just trying to live life. It’s the simple things I treasure. Tiggy brings me a little tray with some breakfast, we get up, admire the view, talk about what we’re going to do with the day. Tiggy has her tennis and yoga, I like to read, play some records. Sharing time together is the most important thing. As you get near the end, the conversations become better and better. “

“You have to go with the flow,” says Tiggy. “We are doing quite well on that, Johnnie, don’t you think?” Johnnie gives her an adoring smile. “Our caring journey,” he says. “It’s a love story.”

For information and support, visit carersuk.org

Yahoo News

Yahoo News